Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Environment

Cutting coal has reduced atmospheric mercury in northeastern U.S.

Decreased pollution from coal-fired power plants has led to a decline in the region’s atmospheric mercury since 2000

by Deirdre Lockwood

January 20, 2017

Mercury concentrations in the air in the northeastern U.S. have fallen within the past two decades as a result of closing and regulating regional coal-fired power plants, a new study shows (Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2016, DOI: 10.1021/acs.estlett.6b00452). The study confirms that regional mercury concentrations are mainly affected by regional changes and are not overwhelmed by global mercury pollution, something researchers were not certain of before the study.

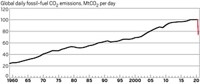

Coal-fired power plants are the largest human-generated source of the neurotoxin mercury to the atmosphere. Some of this mercury—in its oxidized form or bound to particles—reaches waterways, where it builds up in ecosystems and concentrates in fish, threatening environmental and human health. Elemental mercury can stay in the atmosphere for a year or more, so it’s challenging to figure out how much mercury measured in the air in one place comes from local versus global sources—and to evaluate the effectiveness of regulations to lower regional mercury emissions.

To answer this question, Thomas M. Holsen of Clarkson University and his colleagues analyzed atmospheric mercury levels measured in Underhill, Vt., from 1992 to 2014—representing the longest U.S. record of atmospheric mercury data—and in Huntington Forest, N.Y., from 2005 to 2014. They used global and U.S. inventories of mercury and sulfur dioxide emissions from power plants and other sources to determine what influenced these levels.

The team found that mercury in various forms declined between 2 and 8% per year. Prior to 2000, mercury decreases were primarily attributable to decreasing emissions from waste incineration, whereas falling regional power plant emissions were behind decreases since then.

Philip K. Hopke, a study coauthor, says the recent declines in mercury are probably caused mainly by many closures of coal-fired power plants in the region due to economic drivers like the 2008 recession and a shift toward fracking and cheaper natural gas. Placing controls on power plant emissions has also helped, he says.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter