Despite efforts to prevent the industrial fluoroether from getting into North Carolina drinking water, it’s still present. Scientists are racing to find out why

By Cheryl Hogue

February 12, 2018 | Volume 96 Issue 7

Larry Cahoon found out two weeks before most of his neighbors that their tap water held a cocktail of never-before-seen industrial chemicals.

In brief

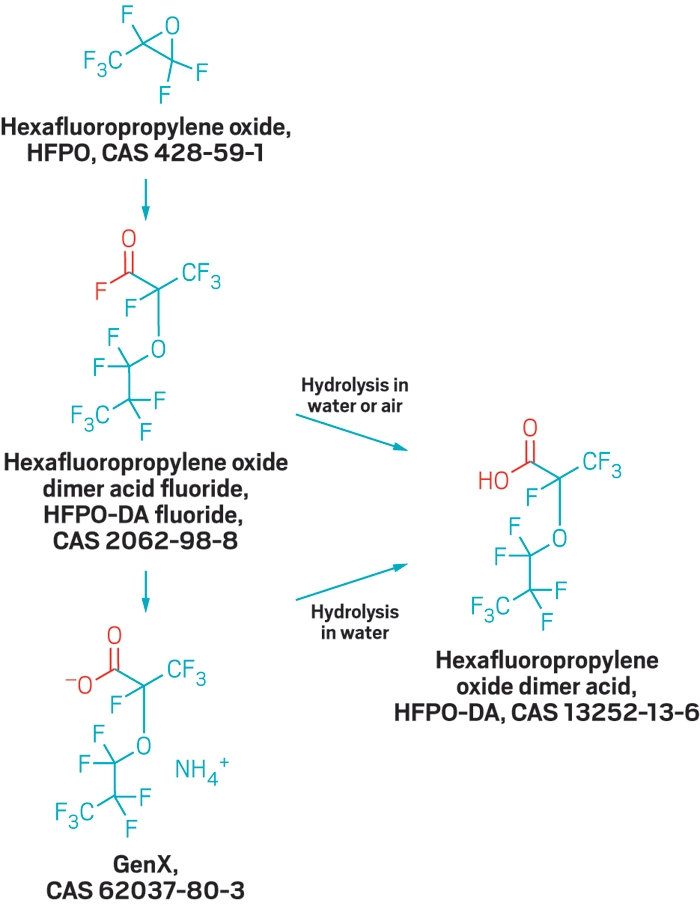

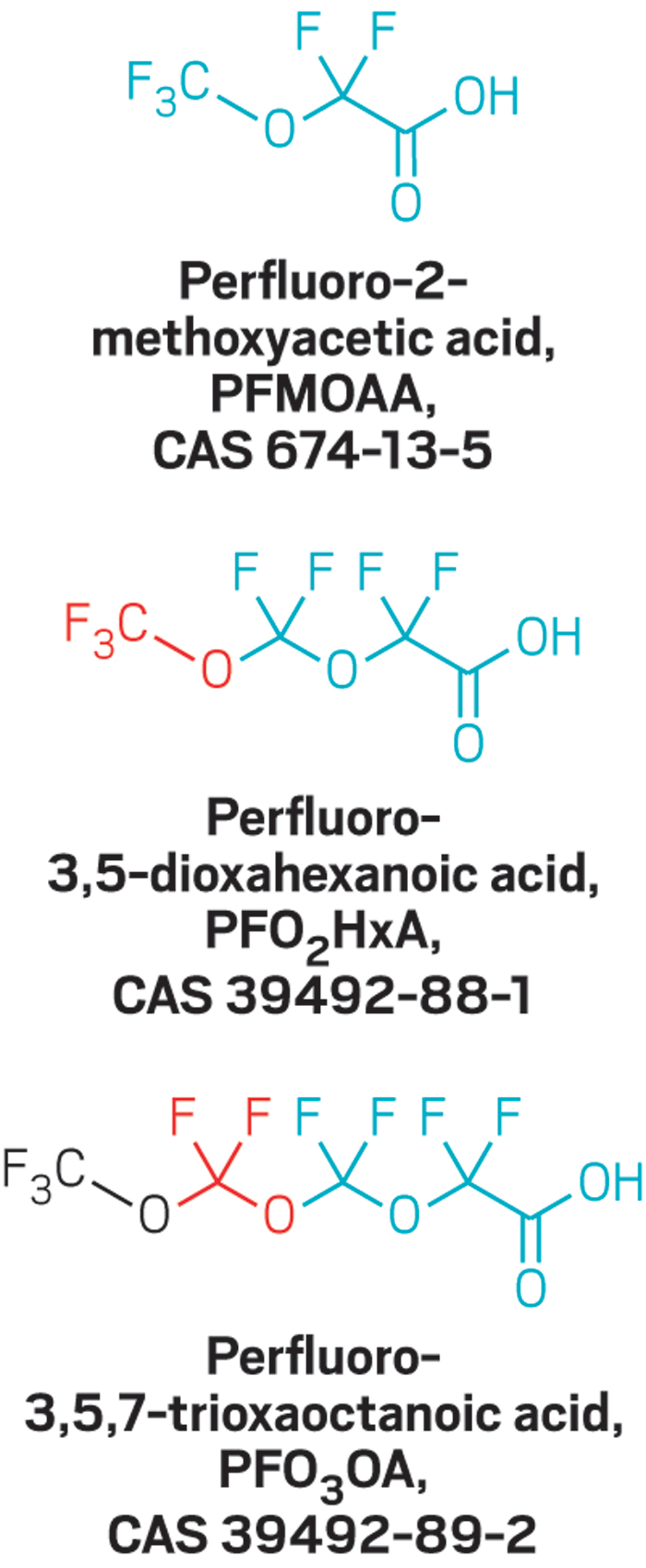

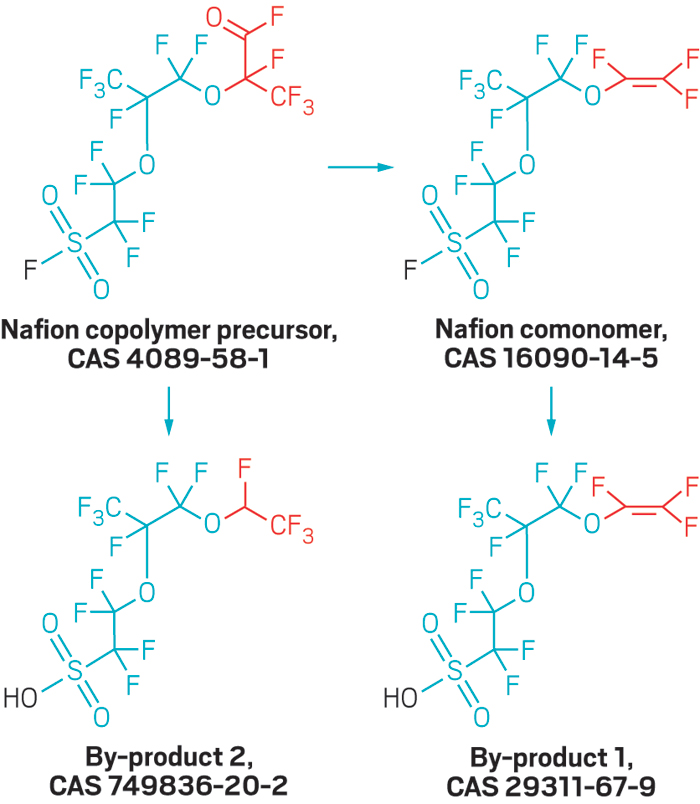

Discovery of a class of industrial compounds called fluoroethers in public tap water last year shocked hundreds of thousands of North Carolina residents who had been drinking the tainted liquid. The source of that contamination is a Chemours fluoropolymer plant that discharged wastewater into the Cape Fear River. The facility now captures all its wastewater for disposal elsewhere. In response, amounts of the substances have dropped, but they haven’t disappeared. Researchers don’t know where the contaminants continue to come from or how they may have affected the health of people who consumed them, but they are conducting studies to find out.

Advertisement

Last May, Cahoon invited a handful of scientists to talk with a local group working to restore striped bass and other migratory fish in North Carolina’s Cape Fear River. At that event, one of the panelists discussed a recently published study that found perfluorinated ethers in a municipal drinking water system that draws from the river (Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2016, DOI:10.1021/acs.estlett.6b00398).

Cahoon, a University of North Carolina, Wilmington, biology professor who studies aquatic ecology, had read the paper and surmised that the chemicals came from a Chemours plant on the outskirts of Fayetteville, N.C. But the study did not name the town with the contaminated tap water.

The panelist, however, did name the locale: The affected city was Wilmington, N.C., said Detlef Knappe, a North Carolina State University engineering professor and coauthor of the paper.

“I had this ‘oh crap’ moment,” Cahoon says. More than a quarter-million people—including Cahoon and his family—get their drinking water from the stretch of the Cape Fear River that runs southeast from Fayetteville to Wilmington. Most of Cahoon’s neighbors in Wilmington learned about the fluorinated substances in their tap water a few weeks later, when the local newspaper, the Wilmington StarNews, launched an ongoing series of articles delving into the pollution.

“That’s when the shit hit the fan,” Cahoon says.

Advertisement

The Wilmington water utility and North Carolina officials scrambled to stop the contamination. Standard drinking water treatment cannot remove the polyfluorinated ethers, so the state asked Chemours to halt a vinyl ether production process that generated the compounds. Later, after a spill at the plant, the state revoked the company’s wastewater discharge permit for its fluorochemical production unit. Chemours now hauls all fluorochemical production wastewater from the Fayetteville facility via tanker truck and rail to Deer Park, Texas, for disposal in a deep injection well, the company told the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency in November.

Those measures have resulted in “a precipitous decline in the concentrations” of fluorochemical substances downstream, DEQ says.

But scientists are still finding fluoroethers in the river. Where the chemicals are coming from is a mystery. And no one knows whether exposure to these chemicals might harm people’s health or the environment.

Despite repeated requests, Chemours did not respond to C&EN’s inquiries for this story.