Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Microbiome

Lactose-munching gut bacteria fuel problems after bone marrow transplants

Graft versus host disease is worse in people who develop Enterococcus blooms after bone marrow transplants

by Megha Satyanarayana

December 13, 2019

People preparing for bone marrow transplants might one day get this advice from their doctors: cut lactose from your diet.

An international group of researchers has discovered that lactose, the sugar in milk and some milk products, spurs the temporary overgrowth of gut bacteria called Enterococcus, and that this overgrowth encourages a sometimes deadly immune response in transplant recipients called graft versus host disease (GVHD).

The findings help explain an observation that people who have less diversity in their gut flora after bone marrow transplants tend to develop more severe forms of GVHD and tend to have poorer outcomes than people who maintain diverse microbiomes, says Jonathan Peled, a transplant and microbiome scientist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) who led the research team along with Marcel van den Brink, another transplant scientist at MSKCC (Science, 2019. DOI: 10.1126/science.aax3760).

Finding lactose as the connection between the microbes and GVHD was a surprise, Peled says, crediting the overlap between their human and mouse bacterial sequencing experiments for pointing the way.

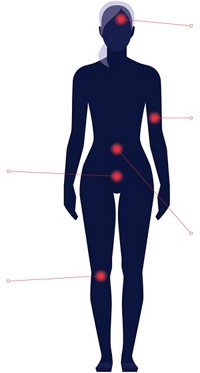

When people get bone marrow transplants, they not only receive the stem cells that will rebuild their blood system, but they also get immune cells from the person that donated the marrow. In GVHD, those immune cells attack the recipient’s organs and tissues, sometimes causing severe damage. People can die from organ damage caused by GVHD. Doctors often prescribe steroids to try to cut down on damaging inflammation that comes with the attack. In some people, GVHD can become a chronic condition.

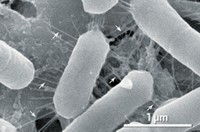

To study the relationship between the gut microbiome and GVHD, the team studied stool samples from 1,325 transplant recipients at hospitals in the US, Japan and Germany. Within three weeks of their transplant, up to 65% of patients from each hospital developed an overgrowth of E. faecium. Enterococcusspecies typically make up less than 0.1% of a healthy person’s gut flora. Some people in the study had gut microbiomes that were up to 30% Enterococcus species.

Scientists and clinicians worry about these species, especially E. faecium and E. faecalis, because they can become pathogenic and are often resistant to antibiotics. In the transplant study, those people with the Enterococcus blooms had a lower survival rate, and the researchers believe that was due to GVHD.

When the researchers sequenced the DNA from fecal samples of the transplant patients, they found that genes involved in lactose metabolism were heavily represented. They also sequenced the genomes of some of the recipients and found that those with a genetic mutation linked to lactose intolerance had longer lasting Enterococcus blooms after the procedure than those without the mutations.

They observed similar findings in mice receiving bone marrow transplants—both the E. faecalis connection to GVHD and the heavy representation of lactose metabolism genes in stool samples from animals with E. faecalisblooms. Giving the mice lactose-free food reduced the overgrowth of Enterococcus and reduced the severity of GVHD.

Peled says the researchers next would like to test how dietary changes affect the outcomes for people undergoing bone marrow transplants. But based on an interesting observation during their studies, he hints that it might be easier to give people an over-the-counter lactase supplement, which contains an enzyme that breaks down the sugar. After a lot of trial-and-error to create bacterial growth medium without lactose to do their studies, Peled says they discovered that over-the-counter lactase tablets cleared the sugar from their media like a charm.

Pavan Reddy, a transplant and microbiome researcher at the University of Michigan, says he’s curious what exactly Enterococcus is doing to exacerbate GVHD. He says it’s interesting that a short-term bloom has such a large impact on an ongoing immune response like in GVHD. One possible explanation, he says, is that a metabolite released in large quantities from Enterococcus is directly exacerbating the condition, but it’s also possible that the loss of a beneficial metabolite from a bacterial species that Enterococcusoutcompetes could make GVHD worse.

Peled and Reddy both point out that in many bone marrow transplant recipients, elevated levels of Clostridia species have been connected to a reduction in the incidence of GVHD through a mechanism involving the metabolite butyrate. Reddy is involved in a clinical trial of adding specific starches to the diets of bone marrow recipients in the hope of bolstering Clostridia populations.

“The excitement really is to do simple things to reduce GVHD burden through diet,” Reddy says.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter