Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Neuroscience

Alzheimer’s protein may stabilize activity in the brain

Researchers determine that a nonpathogenic form of amyloid precursor protein binds to a brain receptor to balance electrical activity

by Megha Satyanarayana

January 10, 2019

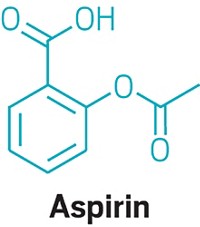

Amyloid precursor protein (APP) is famous for its role in Alzheimer’s disease—enzymes in the brain chop up the protein, forming a version called amyloid β that clumps up and kills neurons. But for 30 years, neuroscientists have been trying to figure out what the nonpathogenic versions of APP do in the brain.

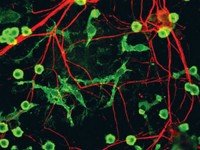

Studies have shown that one version of APP can help balance the electrical activity of neurons by helping reduce the release of chemical signals called neurotransmitters sent from one neuron to another—a key part of synaptic transmission in the brain. Now a team of Belgian and US scientists report that APP’s partner in this process is a protein on the surface of neurons called GABABR1a (Science 2019, DOI: 10.1126/science.aaw0636).

It’s not clear yet if upsetting the interaction between APP and GABABR1a contributes to the development of Alzheimer’s disease, says Heather Rice of the VIB-KU Leuven Center for Brain & Disease Research, who was the study’s lead author. But she points out that people with the disease exhibit a burst of neuronal hyperactivity before symptoms set in, and that burst is related to disruptions in signaling involving the neurotransmitter GABA, which also binds to GABABR1a.

“There may be other binding partners,” Rice says of APP, “and I myself doubt that this is the only function of [APP] in the brain. But for synaptic transmission, this may turn out to be the most important for understanding Alzheimer’s disease.”

APP often sits in the membranes of neurons. The cells also secrete versions of the protein, and one of these is the form that has been implicated in reducing neurotransmitter release. In the new study, the team took a secreted form of APP and looked for binding partners in extracts of rat synapses. They pulled out GABABR1a. When the researchers measured the impact of APP binding to GABABR1a on electrical activity in mouse hippocampal neurons, they observed changes that indicated a reduction in neurotransmitter release, showing that this interaction might drive a change in neuronal activity.

Rice says the next steps are to determine in what cell types and in what brain circuitry this interaction is crucial for controlling electrical activity and neurotransmitter signaling.

Jerold Chun, a neuroscientist at Sanford Burnham Prebys Medical Discovery Institute recently published a paper revealing that the brain can produce significantly different versions of the APP protein. He is interested in seeing if other APP variants reduce neurotransmitter release through GABABR1a, and wonders if the effect might be different in Alzheimer’s disease.

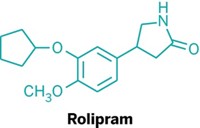

Neuroscientist Martin Korte of Technical University of Braunschweig, who discovered another binding partner for APP in the acetylcholine receptor family, wonders if figuring out nonpathogenic APP’s binding partners may lead to possible drug design strategies. For example, drugmakers could look for compounds that tilt the scales away from APP being cleaved into pathogenic variants like amyloid β, and more toward housekeeping variants like the ones studied in this new study. “It gives industry something to think about. Everyone is looking at amyloid β, so here you go a step earlier, and prevent amyloid beta by promoting [protective forms of] secreted APP,” he says.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter