Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Persistent Pollutants

Understudied class of PFAS found in healthcare facilities

Indoor dust and wastewater reveal fluorotelomer ethoxylates, which likely originate from stain repellents and anti-fogging spray

by Krystal Vasquez

December 7, 2022

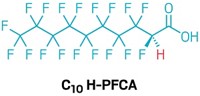

Researchers have detected an understudied class of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), known as fluorotelomer ethoxylates (FTEOs), in indoor dust and industrial wastewater samples collected across two provinces in Canada. They found the highest concentrations of FTEOs in dust found in healthcare settings, such as a hospital, a pharmacy, and a medical school, and in effluent produced at a healthcare linen cleaning facility (Environ. Int. 2022, DOI: 10.1016/j.envint.2022.107634).

According to the study's corresponding author, Karl Jobst, an environmental chemist at Memorial University of Newfoundland, investigating the prevalence of FTEOs in healthcare facilities complements previous work done by other groups, which have identified these potentially persistent fluorinated compounds in fabric stain repellents and anti-fogging agents (Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2014, DOI: 10.1007/s00216-014-7862-0). “We certainly hypothesized that these compounds could be widespread,” says Nicholas Herkert, an environmental scientist at Duke University who detected FTEOs in anti-fog sprays earlier this year (Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, DOI: 10.1021/acs.est.1c06990). “But so little research has been done on FTEOs to date, we were ultimately uncertain.”

The new study is the first to confirm Herkert’s suspicions. To measure FTEOs in the dust and wastewater samples, Jobst and his colleagues attached a mass spectrometer to a gas chromatograph using an atmospheric pressure chemical ionization source. According to Jobst, this analytical setup can detect FTEOs more easily than liquid chromatography, the primary method for detecting PFAS in environmental samples. He suspects that the prevalence of liquid chromatography in PFAS analysis prevented scientists from detecting FTEOs in the environment prior to this study.

The concentrations of FTEOs in the dust and effluent samples were in a similar range to more well-known PFAS, such as perfluorooctanoic acid. In addition to healthcare facilities, the fluorinated ethoxylates were also found at an electroplating facility, a plastics recycling center, and a cosmetics manufacturer, albeit in smaller amounts. “It’s somewhat startling to see just how widespread these FTEOs are detected,” Herkert says. “Further work is definitely warranted to further characterize uses, persistence, and toxicity of FTEOs.”

Jobst agrees, noting that this work is already underway in his lab. Some researchers in his group have already begun exposing mice to FTEOs to better understand the compound’s health effects. Meanwhile, others are collecting and analyzing more samples to determine just how ubiquitous these compounds are. Jobst and his team are also in the process of taking a deeper look at the samples analyzed in this study, which they believe contain other classes of PFAS that have not yet been identified. “This is just the tip of the iceberg,” he says.

CORRECTION:

This story was updated on Dec. 8, 2022, to correct Karl Jobst's role in the study. Jobst is the corresponding author, not the lead author.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter