Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Pollution

Air pollution hurts honeybees

Dirty air poses an additional health threat for these important pollinators

by Janet Pelley, special to C&EN

August 11, 2020

Bees are in rapid decline across the globe, stressed by pesticides, diseases and lack of diverse food sources. Now, air pollution can be added to the list of stressors. A new study of honeybees in India finds that air pollution impairs the pollinators’ behavior, survival and health (Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2020, DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2009074117).

Nearly three-quarters of the world's crop plants depend on bees and other pollinators. As bee populations plummet, scientists want to understand the drivers of the decline. Shannon Olsson and her team at India's National Centre for Biological Sciences suspected that air pollution could be affecting the city’s pollinators.

“Even though there is a huge body of literature on air pollution and human health, there are very few studies that have looked at its physiological effects on other organisms such as bees,” says Geetha Thimmegowda, a chemical ecologist on the team. The scientists decided to focus on the giant honeybee (Apis dorsata), a wild bee native to South and Southeast Asia. This bee produces more than 80% of the honey in India.

The researchers chose sites across Bangalore representing high, moderate, low and rural levels of particulate air pollution. For each site, the scientists recorded average concentrations of particles that measure less than 10 µm across, denoted as PM10. The World Health Organization guideline for PM10 is 20 µg/m³. Levels at the team’s study sites ranged from 99 µg/m3 at the highly polluted site down to 28 µg/m3 at the rural site.

Thimmegowda found twice as many bees visiting the flowers of a common tree at the site with lowest pollution as at the highly polluted site.

“The significant reduction in bees gorging on flowers in more polluted habitats demonstrates the direct link between pollution and an impact on the environment,” says Mark Winston, a bee biologist at Simon Fraser University who was not involved in the study. Fewer bees on flowers means poor pollination and great losses in crop production and the integrity of natural ecosystems, he says.

To more closely study giant honeybee health, the researchers caught insects at each site and brought them back to the lab. After one day, survival differences became clear: 80% of the bees from the highly and moderately polluted sites had died while only 20% of bees from the low-polluted and rural sites perished. “The time that a bee lives is very significant because the colonies depend on particular lifespans of the many thousands of workers and they’re extremely sensitive to any perturbations in those lifespans,” Winston says.

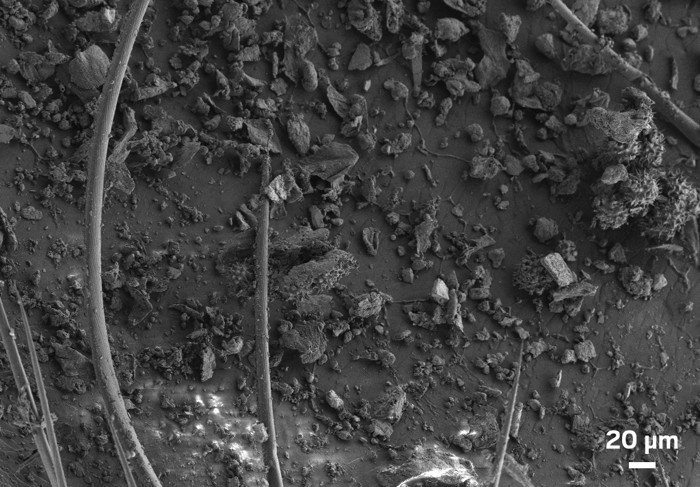

Next, Thimmegowda looked for direct evidence of the burden of air pollution. “Bees have finely tuned external skeletons through which they breathe, control water loss and detect pheromones, so having particles coating it is really disturbing,” Winston says. Under the electron microscope, Thimmegowda saw that bees from the highly polluted site had a larger area covered by tiny particles laced with toxic metals compared to bees from other sites.

Delving into the bees’ physical health, the researchers tallied nearly three times as many blood cells in bees from the low polluted site compared to the highly polluted site. Furthermore, bees from the highly polluted site were more likely to have irregular heart beats. Higher air pollution exposure also altered the expression of genes involved in stress, immune function, and metabolism—all important for survival. “Many of these gene alterations have also been documented with pesticide exposures,” Thimmegowda says.

The study points out that air pollution doesn’t have a single impact on bees, but a multitude of health impacts, Winston says. “We know enough about threats to bees to begin cleaning up the world around us, including the air,” he says.

Correction

This story was updated on Aug. 11, 2020, to delete an incorrect statement about pollinated plants producing 90% of the world's food and to correctly attribute the idea for the bee pollution study, which came from Shannon Olsson, not Geetha Thimmegowda.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter