Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Pollution

Researchers find microplastics in clouds

The chemical composition of the plastic pieces suggests they could promote cloud formation, indirectly affecting the climate

by Krystal Vasquez

October 2, 2023

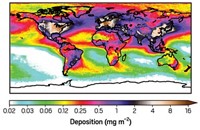

Microplastics have infiltrated nearly every corner of the globe. Now, a new study suggests they’ve made their way into the clouds.

Researchers from Waseda University identified nine types of microplastics in cloud water that they collected from the summit and foothills of Mount Fuji and the summit of Mount Oyama, both of which sit to the southwest of Tokyo (Environ. Chem. Lett. 2023, DOI: 10.1007/s10311-023-01626-x) .

The number of microplastic particles that the researchers found in the cloud water was low—between 7 and 14 pieces per L on average—but that number is likely an underestimate, says Hiroshi Okochi, an environmental chemist at Waseda University and one of the study’s authors. Okochi explains that the collection equipment he and his team used was not originally developed to sample microplastics.

Even so, “it’s a unique dataset which fills in some knowledge gaps regarding microplastics environmental distributions,” says Denise Mitrano, an environmental chemist at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH), Zurich, who wasn’t involved in the study.

After collecting the cloud water samples, Okochi and his team analyzed the chemical properties of the microplastics to determine how they might be influencing the atmosphere. The scientists found that the microplastics contained a high number of hydrophilic groups, which form as the plastic deteriorates. “Hydroxyl and carboxyl groups are formed, making it easier to absorb water,” Okochi explains in an email.

This finding led Okochi and his team to conclude that, more than just floating in the clouds, these plastics could be playing a role in forming them. That would mean that microplastics could indirectly alter how rain is distributed or change how much solar radiation reaches the ground, Okochi explains. “At present, we do not know the extent of this risk, so this is an issue for further study,” he adds.

Mitrano agrees that further study is needed, but she is hesitant to draw the same conclusions as Okochi and his colleagues. Just because microplastics are present in clouds doesn’t mean they’re influencing them, she says. “It could mean that they are just being transported with the airmass,” she says in an email.

Even if future research determines that microplastics do play a role in cloud formation, how large of an impact they have on the climate remains to be seen. Mitrano suspects their effect is small, except in more pristine locations where microplastics could outnumber other cloud-forming particles.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter