Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Fermentation

Newscripts

Vectorized vineyards: Big data in wine making

by Laurel Oldach

August 30, 2024

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 102, Issue 27

Suggestions from a silicon sommelier

If you’ve ever walked into a wine store seeking an offering for a dinner party, you know how crowded the market can be. Last year, wineries applied to sell about 126,000 unique labels. “You don’t see that in ketchup,” says industry expert Katerina Axelsson.

Axelsson hopes to help prospective purchasers choose amid this dizzying array of options by using wine chemistry, consumer preferences, and a hefty dose of artificial intelligence.

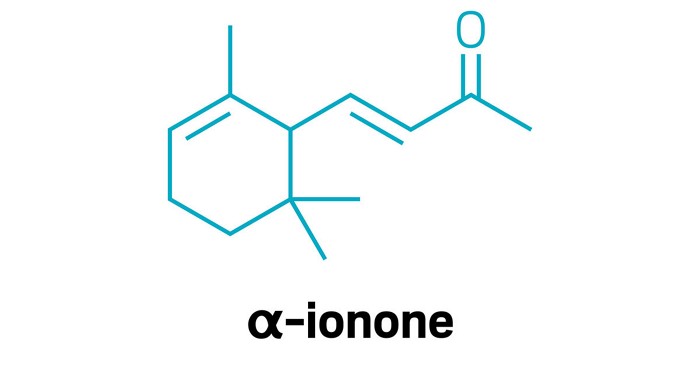

Before founding her company Tastry, Axelsson worked in the analytical laboratory of a winery. “The problem is, machines don’t look at chemistry the way humans do,” Axelsson tells Newscripts. For a spectrometer, ten micrograms per liter of benzaldehyde is ten micrograms per liter of benzaldehyde. But for a human, whether that compound is noticeable depends on its context. Another compound might mask benzaldehyde or might increase its potency—or might make it register as a taste of cherry, almond, or marzipan. And a wine might contain thousands of flavor compounds. As a result of this complexity, although wineries try to base their decisions on chemistry, Axelsson says. “We’re all making multibillion dollars’ worth of product using intuition.”

Enter the modern oracle for complex problems: artificial intelligence. Axelsson trained a model using the chemical makeup of thousands of commercially available wines combined with scores from human tasting panels. By looking more holistically at what combinations of flavorants make certain taste attributes jump out, she says, the model can assess the chemistry of a new mixture more like a human would.

Tastry often describes its project as teaching a computer to taste a glass of wine. This approach sounds odd, but it’s gaining traction among vintners. Winemaker James Hall of Sonoma’s Patz & Hall told the Santa Rosa Press Democrat, “I could see this technology becoming the Dewey decimal system of wine.”

At first, the company’s main market was winemakers looking to blend a better bottle. The model can suggest blending recipes to mask the tainted taste of wildfire smoke or to keep a flavor profile on par with a prior year’s vintage. In recent years, though, they have transitioned to marketing, using the platform like an enormous virtual focus group to help producers target Texas or San Francisco palates.

Though Tastry reports trends by region, Axelsson says the data show that marketing does as much as palate to shape wine preferences. One question she often fields is: What chemistry in a wine appeals to a certain target group? Why, for example, do women aged 20–40 like Kim Crawford’s sauvignon blanc? “The answer is, they don’t,” Axelsson tells Newscripts. “It’s just that marketing captured those consumers.”

A clock in every grape

Unlike papayas, apples, and stone fruits, grapes do not continue to ripen after being plucked, so determining the best time to pick them is a weighty decision. To catch the optimal moment for harvest, winemakers sample their vineyards, often by taste. But their task can be tough because grapes ripen at different rates within a bunch.

Researchers at the University of Montpellier investigated why some grapes dash while others dawdle (bioRxiv 2024, DOI: 10.1101/2024.07.06.602344). Taking a page from single-cell studies that have become widespread, the sauvignon scholars scaled up to single-berry metabolomics and traced a trajectory for the molecular events behind ripening. They identified substages between the phases of growth and ripening that others had described and linked metabolites to grape softening, sugar storage, swelling, and color change.

Each grape within a cluster can reach peak ripeness at a different moment, the researchers concluded, because each grape marches to the beat of its own tiny metabolic drummer. Luckily for winemakers who end up with a variegated bunch, AI-powered grape-sorting machines can choose individual grapes based on ripeness.

Please send comments and suggestions to newscripts@acs.org.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter