Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Profiles

Movers And Shakers

Black chemists you should know about

These inventors, educators, and unsung heroes changed lives through their work in chemistry

by Megha Satyanarayana , Marsha-Ann Watson , Nicholas St. Fleur , Darryl Boyd

February 27, 2019

As she worked her way through college and graduate school in the 1990s, Sibrina Collins was struck by what was missing in her chemistry education: people who looked like her. A young Black woman, fascinated by inorganic chemistry, and all the faces and names in her textbooks were White.

After getting her PhD, Collins told herself that when she became a professor, she would change that. So, while teaching first-year students at the College of Wooster about bonds, valences, and the myriad other introductory chemistry topics, she peppered in stories of chemists like the ingenious Alice Ball, the fruitful Percy Julian, and the groundbreaking St. Elmo Brady. Chemists who looked like her. Chemists who were rarely mentioned in textbooks.

“My goal was really to broaden the image of a chemist in the classroom for all my students to see,” she tells C&EN. “I really do think that chemists, scientists, we are historians. We just tell the stories through the molecules and systems that we study.”

Collins, who is now the executive director of the Marburger STEM Center at Lawrence Technological University, says that beyond broadening students’ horizons, sharing the stories of these distinguished Black scientists helps level the playing field and helps right a far-too-entrenched wrong of disregarding Black achievement in chemistry or even omitting it from the field’s history.

“I was just trying to address equity in some way,” she says.

That was our goal too.

In February 2019, C&EN first published this list of noteworthy chemists in honor of Black History Month. We started with six people whose work has shaped the discipline and whose discoveries have changed our lives for the better. We asked for your feedback on whom to add next, and you responded, sharing stories of your relationships with some of our honorees and urging us to add more. Please keep sending us suggestions. We’ll keep updating.

Alice Ball

by Megha Satyanarayana

Around the turn of the 20th century, leprosy was a major public health concern in Hawaii. Alice Ball was a chemistry instructor at the College of Hawaii, which would become the University of Hawaii. She had earned a master’s degree in chemistry from the institution, looking for active components in a medicinal plant, the kava root. Ball was the first woman and first Black woman to earn a chemistry degree at the university, as well as to become an instructor.

In 1916, Harry Hollmann, a doctor at Kalihi Hospital who was treating people with leprosy, asked Ball to help him determine the active ingredients in chaulmoogra, a plant that had been used with some success to treat the disease. Hollmann was looking to isolate something concentrated and injectable, and in one year, Ball had figured out how to fractionate the active oil, allowing her to solubilize it (Arch. Derm. Syphilol. 1922, DOI: 10.1001/archderm.1922.02350260097010).

Ball died suddenly, at the age of 24, possibly of accidental chlorine poisoning in a laboratory. Her work was taken up by a male scientist who tried to take credit for her discoveries. Chaulmoogra injections based on Ball’s work became a standard treatment for leprosy until the 1940s. In 2000, Hawaii Lieutenant Governor Mazie Hirono named Feb. 29 “Alice Ball Day.”

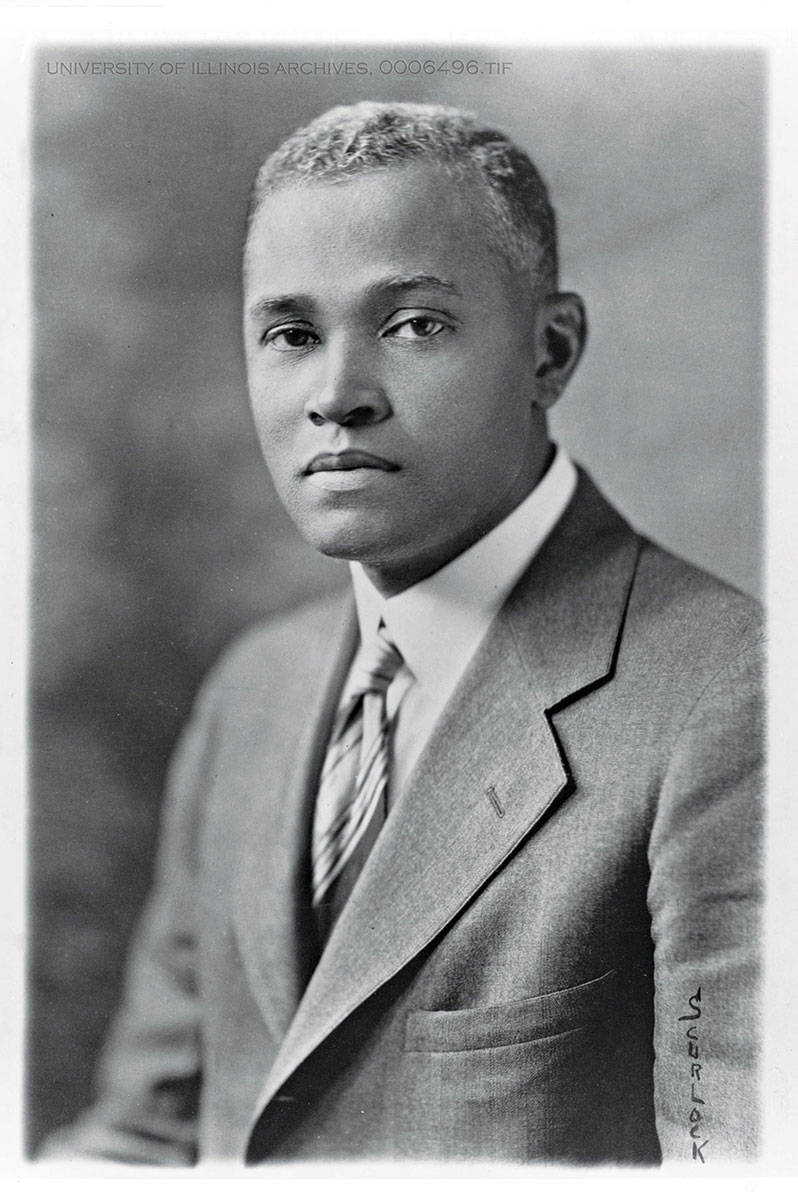

St. Elmo Brady

by Megha Satyanarayana

In 1916, St. Elmo Brady, born in Louisville, Kentucky, became the first African American to earn a PhD in chemistry. He did his graduate work at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, and his research focused on how the acidity of carboxylic acids changed based on the addition of different chemical groups. He taught for several years at what would eventually be called Tuskegee University and eventually became the chair of the chemistry department at Howard University.

Several years later, Brady returned to Fisk University, where he had earned his undergraduate degree, to lead its chemistry department. He took over from another noted Black chemist, Thomas W. Talley.

At Fisk, Brady created the nation’s first graduate program in chemistry at a historically Black college and eventually did the same at three other universities. In 2019, the American Chemical Society awarded Brady a National Historic Chemical Landmark because of his accomplishments. He died in 1966.

Winifred Burks-Houck

by Marsha-Ann Watson

Winifred Burks-Houck was an environmental organic chemist and the first woman president of the National Organization for the Professional Advancement of Black Chemists and Chemical Engineers (NOBCChE), serving from 1993 to 2001.

Burks-Houck was born in Anniston, Alabama, in 1950 and earned her bachelor’s degree in chemistry at Dillard University and her master’s in organic chemistry at Atlanta University. Burks-Houck worked at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory as an environmental chemist for many years analyzing environmental hazards, minimizing potential threats to worker safety, and ensuring that the lab limited environmental impacts during its operation.

But Burks-Houck is best remembered for her work in advancing the interests of Black chemists. During her tenure as NOBCChE president, she developed partnerships with organizations such as the American Chemical Society, the American Association for the Advancement of Science, the Society for the Advancement of Chicanos and Native Americans in Science, and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

After her death in 2004, NOBCChE honored Burks-Houck by establishing the Winifred Burks-Houck Professional Leadership Lecture, Awards, and Symposium. The awards honor professional women as well as students for their achievements in science, technology, engineering and math; leadership; and entrepreneurship.

Marie Maynard Daly

by Megha Satyanarayana

Marie Maynard Daly was the first Black woman in the US to earn a PhD in chemistry. She earned her doctorate from Columbia University in 1947. As a graduate student, she studied the workings of a digestive enzyme, and as a postdoctoral fellow, she investigated the mysteries of the cell nucleus. Her research helped scientists understand histones, proteins that both aid in the organization of our genomes and influence gene expression.

Daly also showed that high blood pressure led to clogged arteries and that high levels of cholesterol were an important contributor to this aspect of metabolic disease. She also investigated the role of smoking in high blood pressure.

Outside the lab, Daly taught at Howard University and Albert Einstein College of Medicine and worked hard to improve the ranks of underrepresented groups in medicine and science. In 1988, in honor of her father, who had to abandon his chemistry degree because of the cost, she started a scholarship at Queens College, where she earned her bachelor’s degree in chemistry.

Charles Drew

by Nicholas St. Fleur

Every 2 seconds, a person in the US needs to receive a blood transfusion, according to the American Red Cross. Since the 1940s, countless people around the world have received a second chance at life thanks to medical advancements made by Charles Drew, the father of the blood bank.

Drew was born in 1904 in Washington, DC. An athlete since a young age, he attended Amherst College on a scholarship for football and track and field. Though he excelled against challenges on the grass and gravel, he faced racism and segregation both in athletics and in academics. After graduation, Drew pursued medical studies at McGill University College of Medicine, a place known for treating its Black students with more respect than similar institutions in the US. In 1933, he graduated second in his class of 137.

He had a keen interest in blood transfusions, but like all Black scholars, he was barred from pursuing this interest at the Mayo Clinic, where he had hoped to study. So he began work at Howard University School of Medicine as a teacher, and enrolled at Columbia University to pursue a doctorate degree. In his graduate research, he found that blood could be preserved longer once the plasma and the red blood cells were separated. This insight extended how long blood could be stored from a couple of days to a week. This discovery was well timed: World War II was breaking out in Europe. Britain, in need of Drew’s expertise, called on him to start a blood bank in 1940.

The American Red Cross too called upon Drew. He fought against the group’s insistence that Black and White blood be segregated, because there was no scientific merit for the separation. Drew eventually resigned in protest because the organization refused to end the practice.

On April 1, 1950, at the age of 45, Drew overturned his car while driving through North Carolina to a medical conference. He was rushed to a segregated White hospital, and despite receiving a blood transfusion, died of his severe wounds. Mere months after his death, the Red Cross ended its segregated blood donation program, ending one of the final racial barriers that Drew poured his blood and sweat into toppling.

Lloyd Noel Ferguson

by Megha Satyanarayana

When he was young, Lloyd Noel Ferguson was a literal backyard chemist, inventing a moth repellent and a spot remover in the yard behind the Oakland home where he grew up. In 1943, he became the first Black person to earn a Ph.D. at the University of California, Berkeley. He worked on a defense project, creating products that might release oxygen for use in submarines.

Eventually Ferguson switched coasts, moving to Howard University to teach and lead that school’s chemistry program. As a researcher, he studied several topics, including the chemistry of taste. He was part of the team that created Howard’s chemistry doctoral program, the first at any historic Black college or university. Ferguson was relentless in creating opportunities for Black people interested in chemistry and biochemistry and received a Guggenheim Fellowship. He was one of the cofounders of NOBCChE, the National Organization for the Professional Advancement of Black Chemists & Chemical Engineers. The organization named an award after him that reflected his passion for bringing up the ranks of young Black chemists—the Lloyd N. Ferguson Young Scientist Award for Excellence in Research. He died in 2011.

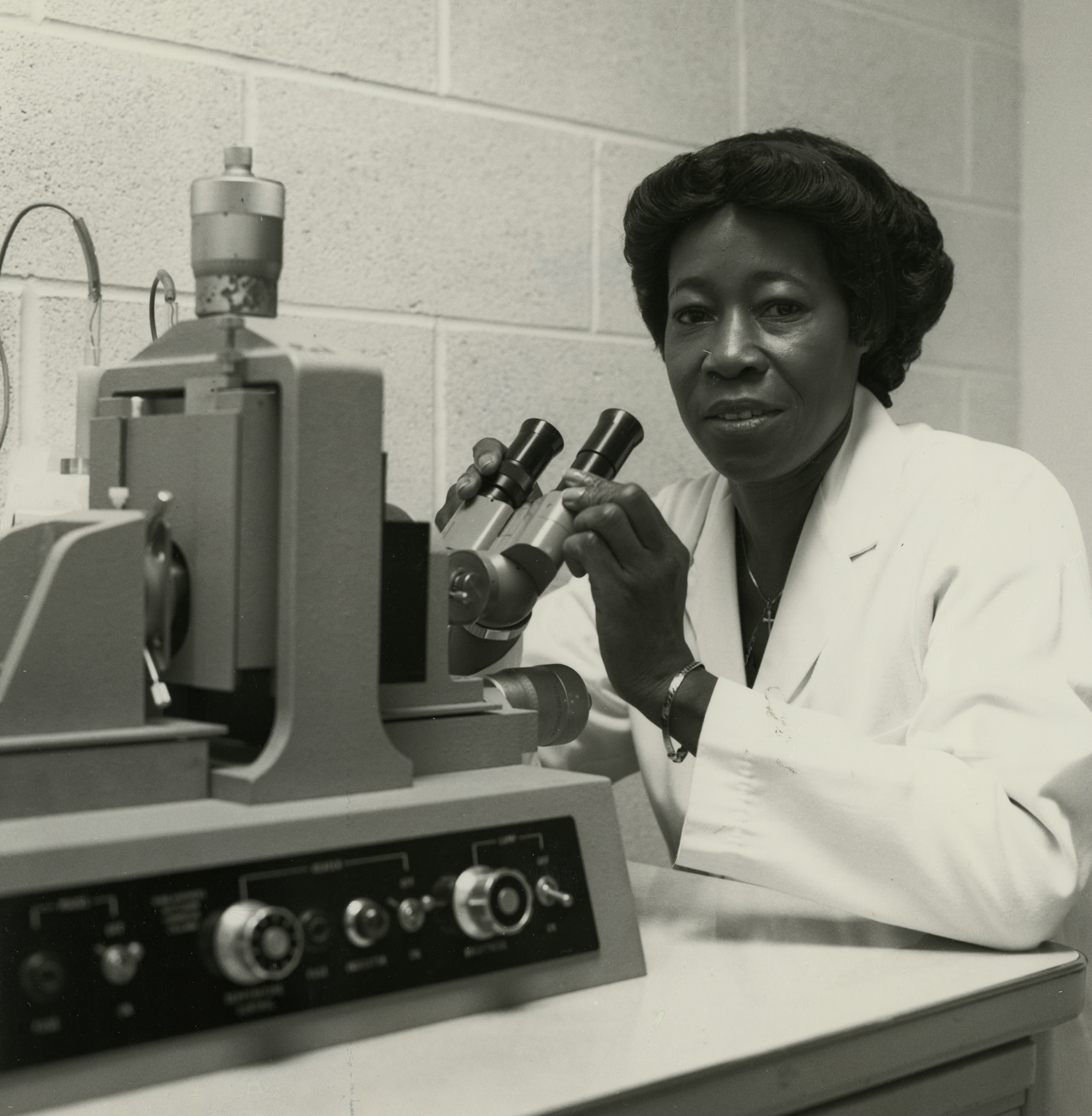

Bettye Washington Greene

by Megha Satyanarayana

In 1965, in the years before riots over civil rights engulfed parts of Detroit, Bettye Washington Greene was putting the finishing touches on her Ph.D. in physical chemistry from Wayne State University. Her thesis focused on how particles distribute themselves in emulsions, and this research served her well. Later that year, Bettye Washington Greene became the first Black woman to work for Dow Chemical.

While at Dow, she worked on developing colloids and on ways to improve latex. She published several papers related to work in developing polymers, including studying different properties that lend to the redispersement of latex.

Among Greene’s many accomplishments are several patents related to latex, including a latex-based adhesive using a carboxylic acid copolymerizing agent, and latex polymers with phosphates used as coatings. Greene died in 1995.

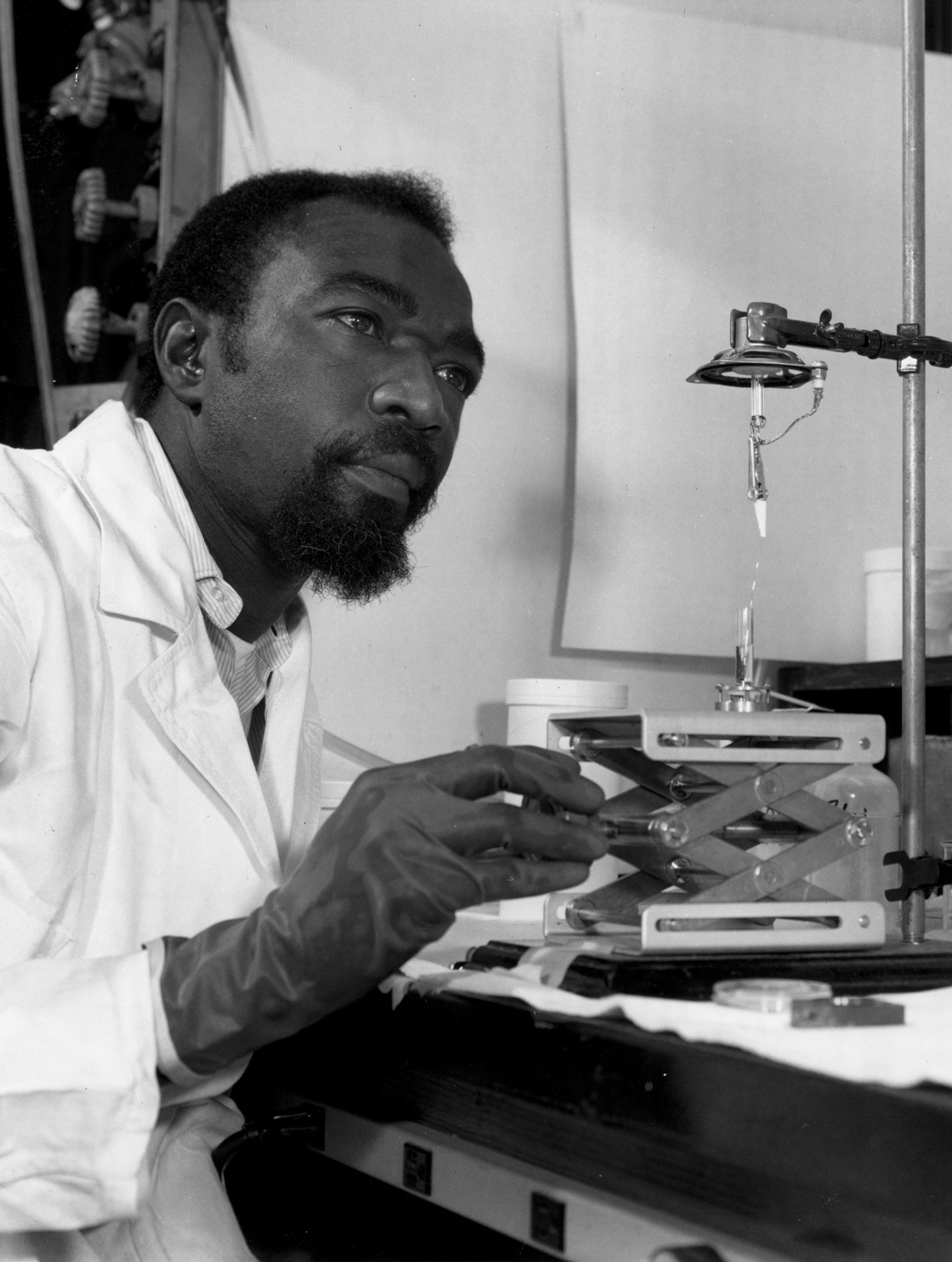

James Andrew Harris

by Darryl Boyd

The discovery of an element is a rare occurrence. Defying racial and academic expectations, James A. Harris played a prominent role in the discovery of two elements.

Harris, who grew up in both Texas and California, earned a bachelor’s degree in chemistry in 1953 from Huston-Tillotson College in Austin, Texas. He then served in the US Army, ultimately earning the rank of sergeant. After his honorable discharge from the Army, he struggled to find work as a chemist due to racial discrimination, as most potential employers did not accept that a Black man was qualified to work in science. Harris eventually landed a job as a radiochemist at Tracerlab in Richmond, California, in 1955, where he worked for 5 years.

His most noteworthy work was at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in the 1960s and 1970s. Despite not having a PhD, Harris thrived at the national lab, leading the Heavy Isotopes Production Group as a part of the Nuclear Chemistry Division. His primary job was to prepare targets for the discovery of heavy elements. These are the materials that scientists bombard with elementary particles and nuclei from other atoms in order to forge new elements. While working with Harris to produce heavy elements, famed nuclear chemist Albert Ghiorso once noted that Harris’s target was “the best ever made for heavy element research.” A major factor in his successful preparation of these targets was his proficiency in executing difficult chemical separations.Thanks to Harris’s persistence and scientific acumen, his team discovered two elements: element 104, rutherfordium, and 105, dubnium.

An avid golfer, traveler, science communicator, and devoted family man, Harris retired in 1988 after 28 years of service at LBNL. He died in 2000, leaving behind his wife and five children.

Walter Lincoln Hawkins

by Megha Satyanarayana

The cables used for telephone lines need to be protected from the sun’s rays, water, and heat, among other things. Before the 1950s, these cables had protective coatings made from either toxic lead or plastics, which, at the time, were prone to rapid degradation via oxidation.

Enter Walter Lincoln Hawkins, a chemist at Bell Laboratories and the company’s first Black employee in a technical position. He and a partner developed a cable sheath made of a then-new class of thioether compounds and carbon black, combined with polyethylene. The work improved the lifespan of telecommunication cables to up to 70 years and led to the expansion of telecommunications all over the world. This sheath was one of dozens of products patented by Hawkins in his lifetime. He held multiple positions at Bell and was inducted into the National Inventor’s Hall of Fame.

Hawkins believed strongly in mentoring minority students, leading a project by the American Chemical Society to promote chemistry as a subject and a profession. In 1992, President George H. W. Bush awarded him the National Medal of Technology & Innovation, in part for his work in helping rural communities establish telephone communications. He died just two months later.

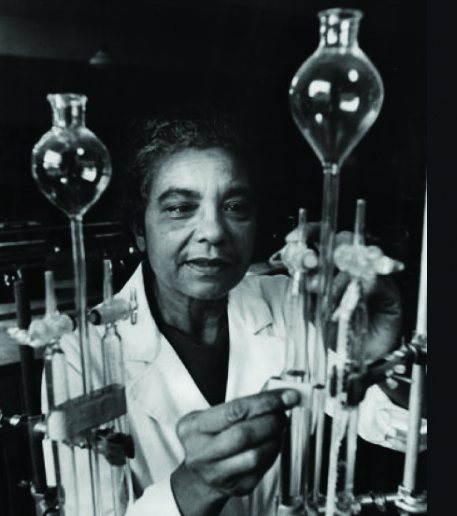

Alma Levant Hayden

by Megha Satyanarayana

In 1963, two doctors named Stevan Durovic and Andrew C. Ivy were treating cancer patients with krebiozen, a compound they called a cure for the disease.

Except that it wasn’t, and Alma Levant Hayden, then a scientist at the National Institute of Arthritis and Metabolic Diseases, showed the world why. After federal researchers coaxed the tiniest samples from the doctor and his partner, Hayden analyzed krebiozen. The results were stunning. This compound being touted as a cancer cure was nothing more than creatine, a molecule readily available in our diets.

Hayden was among the first federal scientists of color, working at what would become the National Institutes of Health and then the Food and Drug Administration. She specialized in using spectrometry to detect steroids. At a career forum for young women in 1962, Hayden told the mostly high school attendees, “Always try to do the very best and to be the very best in whatever group you are working with.” She died in 1967.

Mary Elliott Hill

by Megha Satyanarayana

Mary Elliott Hill was a chemist and teacher who worked alongside her husband, Carl Hill, for many years in the mid-1900s. The duo specialized in plastics, using Grignard reactions to form ketenes, highly reactive compounds used in the formation of esters, amides, and other challenging compounds. Hill was an analytical chemist, designing spectroscopic methods and developing ways to track the progress of the reactions based on solubility.

Hill was born in 1907 in South Mills, North Carolina. She earned a bachelor’s degree in chemistry in 1929 from what would eventually be called Virginia State University. Throughout her career, she taught high school– and college-level chemistry. In 1951, she became the head of the chemistry department at Tennessee State University, eventually leaving to become a professor at Kentucky State College when her husband was named the school’s president.

Hill instituted student chapters of the American Chemical Society at some of the historically Black colleges and universities where she taught. Many of her students became chemistry professors, and she won awards for her teaching. In the 1960s, she observed that more women were becoming interested in science, but they lost interest because of the realities of research life at that time. Hill died in 1969.

Percy Lavon Julian

by Megha Satyanarayana

Percy Lavon Julian made many discoveries in a wide array of chemical disciplines, and all during an era in which segregationist laws limited Black Americans’ access to higher education. Born in 1899 in Montgomery, Alabama, he left the South to enroll at DePauw University, where he had to take high school classes at the same time as his college courses to fulfill the university’s undergraduate requirements.

After receiving a master’s degree from Harvard University, Julian taught, first at Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee, and then at Howard University, where he became the chair of the Chemistry Department. He then went to Austria to get his doctoral degree in organic chemistry at the University of Vienna. Afterward, Julian returned to DePauw and began the hallmark research that would eventually lead to his 11-step synthesis of physostigmine, an alkaloid in the Calabar bean that can be used to treat glaucoma.

Later in his career, as chief chemist and the director of the soybean section of Glidden, Julian drew from his academic research to develop efficient syntheses of steroids, as well as nonmedicinal products, such as a fire-retardant foam that was used during World War II on gasoline fires. Julian also started his own chemical company, Julian Laboratories, as well as the nonprofit Julian Research Institute. Before his death, he was elected to the National Academy of Sciences.

Angie Turner King

by Marsha-Ann Watson

Angie Turner King was born in 1905, a time when few women—let alone Black women—were scientists, and fewer still earned PhDs. She grew up in McDowell County, part of West Virginia’s coal country. Her grandparents were once enslaved and her father, though uneducated himself, encouraged her to pursue education. Throughout her long career as an educator, she ensured that many others followed her father’s advice.

King graduated high school at 14, then earned a bachelor’s degree in chemistry and mathematics at West Virginia Collegiate Institute (now West Virginia State). King taught chemistry and mathematics at the Teacher Training High School while working on her master’s degree at Cornell University, earning her degree in mathematics and chemistry in 1931.

She then taught high school chemistry for several years before joining the faculty at West Virginia State, her alma mater. There she set about refurbishing the college’s lab to ensure students had a working knowledge of a real lab. In 1955, she earned her PhD in general education at the University of Pittsburgh. She taught at West Virginia State for the remainder of her career and was deeply involved in the university community until her retirement in 1980.

King is remembered for her contributions to science education. During World War II, West Virginia State developed an Army Specialized Training Program and as one of the program’s instructors, she taught chemistry to soldiers. Throughout her teaching career, she mentored students who went on to accomplished careers in science, including Jasper Brown Jeffries, a mathematician and physicist who worked on the Manhattan Project; mathematician Katherine Coleman Goble Johnson, famed for her work calculating spacecraft orbits with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration; and Margaret Collins, an entomologist and civil rights advocate.

King died in 2004. She was a member of the American Chemical Society and the West Virginia Academy of Science.

Robert Henry Lawrence Jr.

by Megha Satyanarayana

Robert Henry Lawrence Jr. was a chemist by training, but he was also the first African American astronaut. Lawrence was born in Chicago in 1935. After graduating from Bradley University with a chemistry degree, he joined the United States Air Force, eventually becoming a test pilot.

Soon after, the Air Force selected him to become an astronaut to work on low-orbit intelligence missions. This program was the precursor to the NASA’s space shuttle program. During his training, Lawrence also got a PhD in physical chemistry from the Ohio State University.

Lawrence never made it into space. In 1967, he died during a training flight at Edwards Air Force Base. He had completed about 2,500 hours of flight time in his short career. Bradley University named a scholarship in Lawrence’s honor, and a school in Chicago was also named for him. On Feb. 14, 2020, a shuttle bearing Lawrence’s name embarked for the International Space Station, carrying, among other things, supplies for scientific research.

James Ellis Lu Valle

by Megha Satyanarayana

James Ellis Lu Valle was an Olympian and a chemist. During the 1936 Olympics in Berlin, Lu Valle won the bronze medal in the 400 m race. This was the Olympics in which Jesse Owens took home four gold medals while Adolf Hitler watched. That same year, Lu Valle earned his bachelor’s degree in chemistry from the University of California, Los Angeles. The university later named a student center after him, making Lu Valle the first student to have his name grace a UCLA building.

After earning a master’s degree from UCLA, Lu Valle pursued his PhD under the guidance of Linus Pauling at the California Institute of Technology. After teaching at Fisk University, a historically Black institution in Nashville, Tennessee, Lu Valle became the first Black person to work for Eastman Kodak. Later in his career, he became director of physical and chemical research at Smith-Corona Marchant in Palo Alto, California. When the company closed, Stanford University asked Lu Valle to lead the first-year chemistry lab, and he agreed, ending his career by returning to education and mentorship.

Samuel P. Massie

by Megha Satyanarayana

At the height of the Manhattan Project, Samuel P. Massie was trying to figure out how to turn uranium isotopes into liquids for use in a bomb. Before joining the project, he had gone to Iowa State University to get a Ph.D. in organic chemistry. He was not allowed to live on campus or work in the same labs as White students. After being denied a draft deferment, he withdrew from the Ph.D. program and took a position working on nuclear chemistry for the Manhattan Project.

Massie eventually got his Ph.D. from Iowa State University and then worked on finding new antimicrobial compounds. In 1982, he patented an antibiotic for treating gonorrhea. In his career, he also focused on education—teaching chemistry and taking an appointment at the National Science Foundation to shape science education across the nation. In 1966, President Lyndon B. Johnson chose him to teach chemistry at the US Naval Academy, making him the first Black person to do so. Many years later, he chaired the department, becoming the first Black person to hold that position.

Massie was always a high achiever, graduating high school at 13 and college at 18. One of his Manhattan Project contemporaries was another accomplished Black scientist named Lloyd Albert Quarterman. Massie died in 2005.

Josephine Silone Yates

by Nicholas St. Fleur

Along with being a writer and civil rights activist, Josephine Silone Yates was the first Black woman to head a college science department. Born in Mattituck, New York, either in 1852 or 1859, Yates grew up living with her parents and maternal grandfather, Lymas Reeves, who was a formerly enslaved man. In grammar school, she was enthralled by physics, physiology and arithmetic, and excelled in her studies. At the age of 11, she moved to Philadelphia to pursue better educational opportunities at the Institute for Colored Youth.

She stayed at the school for a year until her uncle, Rev. John Bunyan, whom she was living with, got a job at Howard University. Yates moved in with her aunt in Newport, Rhode Island, and enrolled in Rogers High School in 1874. There, she was the only Black student. But she more than persisted—she shined. Yates developed an affinity to chemistry that impressed a professor, who encouraged her to further explore her interests through extra lab work. In 1877, just 3 years after enrolling, she graduated as class valedictorian.

Continuing on her educational journey, Yates next attended the Rhode Island State Normal School. There too, she graduated with honors. She passed the teacher’s examination and became the first Black person to be a certified public school teacher in Rhode Island. Yates taught chemistry, physiology, and botany, as well as speaking and English literature classes, at the Lincoln Institute in Jefferson City, Missouri.

Yates soon became the first Black woman to head a college’s science department when she was put at the helm of the institute’s department of natural sciences. She was a civil rights activist, a writer, and a teacher until her death in 1912.

UPDATE

This story was updated on Feb. 21, 2020, to include profiles of St. Elmo Brady, Mary Elliott Hill, and Robert Henry Lawrence Jr. The story was updated on Sept. 29, 2020, to include a new introduction and add profiles for Marie Maynard Daly, Percy Lavon Julian, and James Ellis Lu Valle. The story was updated on Feb. 1, 2021, to include profiles of Winifred Burks-Houck, Charles Drew, James Andrew Harris, Angie Turner King, and Josephine Silone Yates.

CORRECTIONS

This story was updated on Sept. 29, 2020. to correct the positions held by Walter Lincoln Hawkins at Bell Laboratories.

This story was corrected on Feb. 16, 2021, to state that the American Chemical Society honored St. Elmo Brady—not the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Fisk University, Tuskegee University, Howard University, and Tougaloo College—with a National Historic Chemical Landmark in 2019. It was also corrected to say that Mary Elliott Hill was born in North Carolina, not South Carolina.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter