Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Drug Development

Experimental sickle cell drug aims to work around potential toxicity problems

Tested in mice, the compound prevents both sickling of red blood cells and the nontarget binding that has scuttled other drug candidates

by Alla Katsnelson, special to C&EN

February 15, 2021

Few drugs exist to treat sickle cell disease, despite it being one of the most common genetic disorders. Pfizer scientists describe a new compound, now in Phase I clinical trials, that they hope will prevent the sickling of red blood cells while working around toxicity problems that have scuttled other such candidate drugs. The researchers estimate that the compound reaches at least 20% of the body’s hemoglobin and decreases sickling by 37.8% when tested in a mouse model of sickle cell disease (J. Med. Chem. 2020, DOI: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c01518).

Sickle cell disease is caused by a single mutation in the gene encoding a subunit of hemoglobin, a protein that ferries oxygen through the blood stream. The mutation results in warped, sickle-shaped hemoglobin molecules that stick together and cause pileups of red blood cells, which block blood vessels and restrict blood flow to organs—problems that in turn drive organ damage and lead to intense pain. The disease affects about 100,000 people in the US, most of whom are Black, according to the Centers for Disease Control.

Currently, the only curative treatment for sickle cell disease is a bone marrow transplant, but this technique mainly works in children and requires sibling donors. Researchers hold high hopes for a gene therapy currently in trials, but the need for a wider range of treatments remains high, says Jean Leandro dos Santos, a medicinal chemist at São Paulo State University who was not involved in the study.

Several companies have tried to develop small molecule drugs that treat sickle cell disease. These stemmed from a decades-old discovery that vanillin, the compound that gives vanilla its characteristic smell, covalently binds to hemoglobin via its aldehyde group to keep the protein in its healthy conformation (Blood 1991, DOI: 10.1182/blood.V77.6.1334.1334)—though vanillin itself had a weak affinity for hemoglobin as well as other characteristics that made it a poor drug.

Medicinal chemists consider aldehydes to be reactive species than can bind nonspecifically to other proteins and cause toxicity, explains David W. Piotrowski, a research chemist at Pfizer. Researchers halted development of one molecule, tucaresol—which was designed to bind to hemoglobin via its aldehyde group—because of immune side effects. However, in 2019, the US Food and Drug Administration approved Global Blood Therapeutics’ compound voxelotor, which also works in this way.

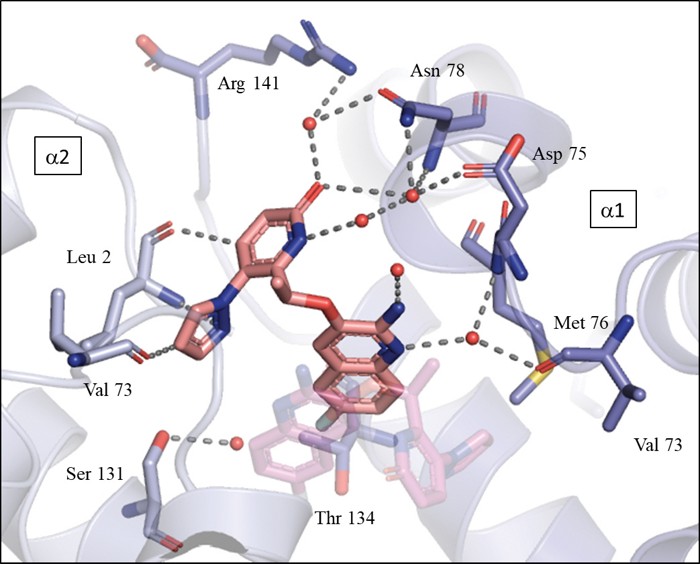

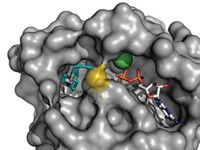

Piotrowski and his colleagues set out to find a molecule that avoids the potential for off-target binding by binding noncovalently. The researchers first screened Pfizer’s compound libraries for molecules that bind noncovalently to hemoglobin. They identified a molecule that forms key interactions with hemoglobin’s α subunits, transiently stabilizing hemoglobin in its oxygenated state to ameliorate sickling. They optimized the molecule by adding an aminoquinoline motif to improve its potency and pharmacological properties.

The resulting molecule is promising, especially because it works via this new approach, Santos says. The company began clinical testing for the compound last year.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter