Day 1

Fly into Berlin, Germany

You’ll return here to see the chemical highlights at the end of your journey. But for now, rent a car and drive south to Freiberg (3 h, 20 min—all times are approximations taken from Google Maps).

Freiberg, Germany

Freiberg is home to TU Bergakademie Freiberg, where Ferdinand Reich (1799–1882) and his assistant, Hieronymus Theodor Richter (1824–98), discovered indium in 1863. Reich’s house still stands. Just a few years later, in 1886, TU Bergakademie Freiberg’s Clemens Winkler (1838–1904) discovered germanium. Visitors touring his laboratory can see some of his original chemicals and equipment as well as a letter to Winkler from Dmitri Mendeleev (1834–1907), credited as the originator of the modern periodic table; appointments for a tour should be made in advance. Mineral buffs will enjoy the Freiberg Mineralogical Collection, also housed at the university, which contains about 80,000 specimens. Travelers who venture about 7 km southwest of Freiberg can also see the Himmelfürst mine, where the minerals that yielded indium and germanium were mined.

Day 2

Chemnitz, Germany

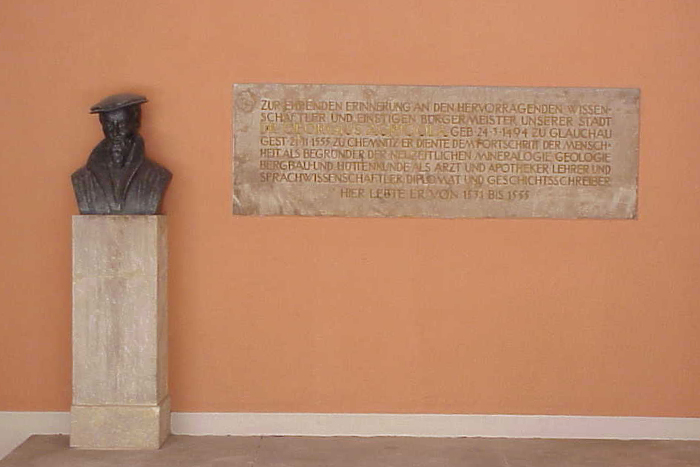

Drive west to Chemnitz (45 min), where metallurgist Georgius Agricola (1494–1555) lived from 1533 to the end of his life. Agricola’s famous book, De re metallica, published after his death, includes early references to bismuth, antimony, zinc, arsenic, and minerals that yielded fluorine and cobalt. Look for the bust of Agricola and the plaque commemorating him in town.

Jáchymov, Czech Republic

Cross over the Czech border and visit the town of Jáchymov (1 h, 15 min), the source of uranium ore wastes that Marie Curie (1867–1934) and her husband Pierre Curie (1859–1906) used to isolate radium and polonium. The town is home to the Radium Palace, a hotel and spa where visitors can get radon baths—with strict exposure limits. Check out the park and monument in town dedicated to the Curies.

Day 3

Johanngeorgenstadt, Germany

Head back to Germany for a stop in Johanngeorgenstadt (35 min). The Georg Wagsfort mine here provided the minerals that chemist Martin Heinrich Klaproth (1743–1817) used to discover uranium. The Pferdegöpel museum focuses on the town’s mining history.

Glauchau, Germany

Hop back in the car and drive on to Glauchau (1 h, 15 min). Learn more about Agricola at Glauchau Castle in an exhibit that Marshall describes as the best in Germany. There’s also a statue of Agricola in a park near the town’s train station.

Jena, Germany

End your day with a trip to Jena (1 h), where Johann Wolfgang Döbereiner (1780–1849) made crucial observations about elemental groupings—an important step in developing the periodic table. The Döbereiner Lecture Hall at Friedrich Schiller University Jena has a small display and a statue of the chemist.

Day 4

Heidelberg, Germany

The long journey southwest to Heidelberg (4 h) ends with the splendid reward of a city rich in chemical history. Heidelberg University has even assembled a chemistry-themed sightseeing tour that drops names such as Erlenmeyer, Bunsen, Helmholtz, Haber, and Bosch. The tour’s elemental highlights reveal that Robert Bunsen (1811–99) and Gustav Kirchhoff (1824–87) established the science of spectroscopy leading to their discovery of rubidium and cesium at the university. Swing by Bunsen’s house and the nearby German Pharmacy Museum.

Karlsruhe, Germany

If you still have some energy, take a detour to Karlsruhe (50 min), where the Karlsruhe Congress convened in 1860, a watershed in the history of chemistry. It was here that Stanislao Cannizzaro (1826–1910) presented his essay of the true atomic weights. This led attendees Lothar Meyer (1830–95) and Dmitri Mendeleev to formulate the periodic table later that decade. The congress’s original building, now a library, still exists.

Day 5

Bad Dürkheim, Germany

Bad Dürkheim, (40 min from Heidelberg and 1 h from Karlsruhe) is home of the spa that furnished the mineral waters that Bunsen and Kirchhoff analyzed when they discovered rubidium and cesium. One of the old salt plants that processed these waters is now a museum.

Darmstadt, Germany

Travel on to Darmstadt (1 h) and visit the GSI Helmholtz Center for Heavy Ion Research, where several transuranium elements, including bohrium, hassium, meitnerium, darmstadtium, roentgenium, and copernicium—the only laboratory-made elements on the tour—were discovered or codiscovered. Tours can be arranged.

Day 6

Göttingen, Germany

Drive north to Göttingen (2 h, 30 min), where Friedrich Stromeyer (1776–1835) discovered cadmium. The building that housed his laboratory still stands. Also in town, the University of Göttingen is home to the Göttingen Museum of Chemistry, where visitors can see historical element samples and other chemistry artifacts. Visitors should contact the museum in advance to arrange a visit. Although it won’t get you another element for your checklist, it’s worth taking in some other notable chemical history in the city. Göttingen was also the home of chemist Friedrich Wöhler (1800–1882). Wöhler synthesized urea, disproving the theory of vitalism, which held that organic compounds could be made only by living organisms. A monument of Wöhler at the university, with a mosaic of urea’s structure at its base, commemorates the accomplishment.

Day 7

Tilkerode, Germany

Driving due east (1 h, 45 min), you’ll find the village of Tilkerode in the Harz Mountains, which Marshall describes as a beautiful area full of forests, meadows, and hiking trails. One trail leads to the mines that furnished the ore that William Crookes (1832–1919) analyzed when he discovered thallium in London. Signs along the trail point out chemically significant sites.

Goslar, Germany

Continue on to Goslar (1 h, 15 min), where you’ll find the Rammelsberg Museum with mining exhibits that include the cadmium-bearing ore that Stromeyer analyzed to discover the element.

Day 8

Varel, Germany

A long drive northwest takes you to Varel (2 h, 50 min), where you’ll find the original home of Lothar Meyer (1830–95), who contributed key insights to creating the periodic table. An interesting sculptural installation called the Three Heads—Meyer, Dmitri Mendeleev, and Stanislao Cannizzaro (see day 4)—sits outside the secondary school that bears Meyer’s name. The busts represent the intellectual interplay between the three that led to the development of the periodic table.

Day 9

Hamburg, Germany

Backtrack a bit and then head northeast to Hamburg (2 h), where 350 years ago Hennig Brand (1630–1710) discovered phosphorus, the oldest of the route’s elemental revelations. The exact location of Brand’s laboratory is unknown, although it was somewhere in the Michaelisplatz square, close to the renowned St. Michael’s Church, which was being built at the time of the elemental discovery.

Day 10

Berlin, Germany

On the last day, get up early and return to Berlin (3 h, 15 min), where the sites of numerous elemental discoveries will finish your quest. The Museum of Natural History highlights Martin Heinrich Klaproth (1743–1817), arguably the most important chemist of his time. He was discoverer or codiscoverer (and often did not take credit, even when he named the element) of uranium, strontium, zirconium, chromium, tellurium, beryllium, and titanium.

The museum is also home to the sample of vanadinite brought from Mexico by naturalist Alexander von Humboldt (1769–1859). Chemical historians note that this sample nearly yielded the discovery of vanadium but for an error by Hippolyte-Victor Collet-Descotils (1773–1815) in France. He misidentified it as containing only chromium. Later in Germany, Gustav Rose (1798–1873) correctly identified that the sample contained vanadium, but the element had already been discovered by then in Sweden.

The Berlin Akademie was destroyed in World War II, but its site can be visited. Here, Andreas Sigismund Marggraf (1709–82) prepared metallic zinc from calamine, differentiated potassium salts from sodium salts, and differentiated alum (an aluminum salt) from lime (a calcium salt). Also at this site, Heinrich Rose (1795–1864, Gustav’s brother) differentiated niobium and tantalum. He named niobium, even though it had previously been discovered—and named columbium—by Charles Hatchett (1765–1847) in England.

Friedrich Wöhler prepared the first metallic sample of yttrium while he was in Berlin; the site is now an apartment complex.

Walter Noddack (1893–1960) and his wife, Ida Noddack (1896–1978), discovered rhenium, the last naturally occurring element identified, in 1925 at the Imperial Physical-Technical Institute (now the National Metrology Institute of Germany).

Otto Hahn (1879–1968) and Lise Meitner (1878–1968) discovered protactinium at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Chemistry, that building is now part of the Free University of Berlin. The original building still exists and is used for biological studies. This university is also famous because it still houses the laboratory where the splitting of the atom was discovered by Hahn and Fritz Strassmann (1902–80) and then explained by Meitner and Otto Robert Frisch (1904–79).

And with that, you’re done. Grab a stein in one of Berlin’s beer gardens and reflect on the chemical tour you’ve completed, spanning 3 centuries of elemental discoveries from phosphorus to copernicium. And make sure to raise a glass to Marshall for planning such a chemically rich vacation.

Credits

Photos and research: James Marshall

Story: Bethany Halford

Editing: Jessica Marshall and Lauren Wolf

Design and illustration: Rob Bryson and Kay Youn

Development: Tchad Blair