FIRST LINE OF DEFENSE

Why ceramides’ critical role in protecting the skin barrier is more important than ever

BY JESSICA AGUIRRE

Contributing Writer, C&EN BrandLab

With the outbreak of the novel coronavirus in 2019 and resulting global pandemic, many people are taking steps to protect themselves. Two of the best ways to prevent transmission are to wear a face mask while in public and wash hands thoroughly and regularly. But this latter precaution, though critical for overall health, can be hard on the skin.

“People are now using more hand sanitizers, hand soap,” and cleaning and disinfecting agents, says dermatologist Debra Jaliman. “Even just rinsing our hands under water as often as is happening now is damaging to the epidermis of our skin,” she adds. “All of these cleaning and disinfecting agents are damaging to the skin when used too often and cause dry skin, itching, and dermatitis.”

Cream formulations containing moisturizing compounds that address or even prevent the damage altogether can be effective. One of the most promising commercially available solutions is a family of lipids called ceramides, which are composed of a sphingoid base and a fatty acid.

Though ceramides have been used in topical applications for a few decades, as an ingredient that can reinforce the skin’s natural barrier against pollution and moisture loss, they are poised to become an important solution for combating the kinds of skin damage that have become more prevalent in the age of SARS-CoV-2.

SKIN DEEP

Ceramides are no stranger to skin. These waxy lipids are natural parts of the skin barrier, representing a major component of the lipid matrix that prevents moisture from seeping out of the skin and some external stressors from permeating the skin. The skin’s outer layer, known as the stratum corneum, is made up of corneocytes: cells that are embedded in a lipid matrix. The intercellular-lipid mortar that binds these corneocyte bricks is made up mostly of ceramides—as well as cholesterol, fatty acids, and cholesterol esters.

“Think of ceramides like grout that fills in the cracks between your skin-cell tiles,” says dermatologist Joshua Zeichner. “They are a great ingredient to help repair a damaged skin barrier. They may help fight off the harm caused by overwashing the skin.”

There are several ceramide subtypes, which perform different functions in protecting the skin. The amount of each ceramide subtype relative to that of the other intercellular lipids is key to forming an effective barrier. Over time, this delicate balance of lipids can degrade, weakening the barrier and contributing to the telltale signs of aging skin. Once we reach our 40s, the ceramide levels in our skin have typically declined by over 60%. Imbalances in ceramide levels or deficiencies in certain ceramide subtypes are also related to conditions such as acne, ichthyosis, psoriasis, and dermatitis.

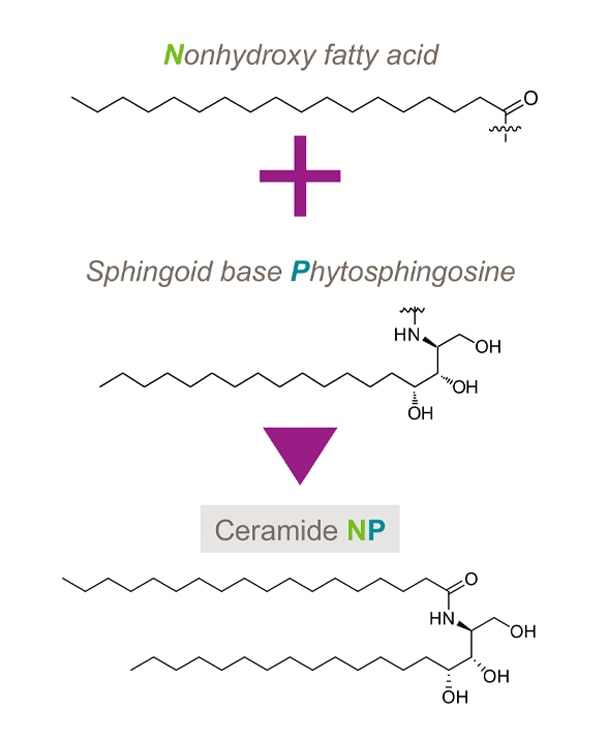

Within the intercellular lipids, ceramides are arranged in a kind of sandwich alternating between different subtypes at regular intervals. Using soaps and other surfactants can affect some ceramide subtypes more than others and cause imbalances that lead to skin damage. In particular, surfactants can cause a deficiency in ceramide III, resulting in what is known as surfactant-induced dermatitis. This condition can be particularly relevant given the present emphasis on handwashing. Also known as ceramide NP, ceramide III comprises a phytosphingosine backbone and a saturated nonhydroxy fatty acid. “You really require ceramides as a building block at the level of fine detail within the stratum corneum, within the lipid barrier,” says Anne Mu, Evonik’s head of innovation management for North America. “You also require the presence of the right types of ceramides in order to contribute to the essential physical layout of the barrier.”

TO THE RESCUE

Evonik, a leader in personal care chemistry, is one of the largest producers of ceramides. The company has been manufacturing ceramides for over 25 years based on its technology for making skin-identical phytosphingosine, an essential sphingoid base. This sphingoid base has the potential to form eight different structures, depending on the orientation of chemical groups around three of the compound’s carbon atoms, but the skin only contains one of these forms. Evonik’s process can selectively produce the type of phytosphingosine found in the skin. To produce skin-identical phytosphingosine, a fermentation process is performed using the yeast Pichia ciferrii, which is derived from the tonka bean—a legume native to Central and South America. The company uses a similar fermentation process to make another sphingoid base, sphinganine, which offers the opportunity to produce a greater diversity of ceramides.

The company then chemically couples the sphingoid base with a fatty acid to produce ceramide. “Varying the sphingoid base and fatty acid results in different kinds of ceramides,” says Ricardo Luiz Willemann, vice president of Evonik’s active ingredients division for skincare.

As consumers become more educated about personal care products, they increasingly seek effective solutions that restore the skin’s barrier using its natural components. Those changing consumer sensibilities coupled with a trend toward greater awareness for proven technologies made the current moment ripe for ceramides to take an even more central role in skin care. As people continue washing their hands to keep COVID-19 at bay, products that reliably protect the skin from degrading will become an important way to maintain a strong defense.

ABOUT SPONSORED CONTENT

Sponsored content is not written by and does not necessarily reflect the views of C&EN’s editorial staff. It is authored by C&EN BrandLab writers and held to C&EN’s editorial standards, with the intent of providing valuable information to C&EN readers. This sponsored content feature has been produced with funding support from Evonik.