Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

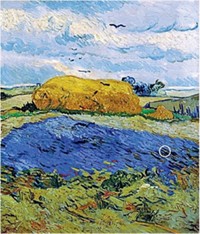

Art & Artifacts

New chemical analysis allows for less invasive dating of artwork

Carbon dating of lead white paint from canvas edges could help uncover forgeries

by Benjamin Plackett, special to C&EN

June 3, 2020

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 98, Issue 22

A new technique determines the age of artworks from lead white paint samples taken from the edges of a canvas, giving experts a less invasive way to uncover forgeries (Anal. Chem. 2020, DOI: 10.1021/acs.analchem.0c00530).

Lead white, used in Europe since at least the Roman period, is one of the oldest and one of the most common pigments used by artists. When the lead in the paint oxidizes, it forms a carbonate, which captures a snapshot of the radioactive carbon-14 concentration in the atmosphere at the time the artwork was created. This should make lead carbonate an ideal candidate for radiocarbon dating techniques. However, the purest samples of white pigment are usually found in the main image, and extracting such a crucial part of an artwork can cause unacceptable damage. Samples taken from the edges of a canvas, though, often contain other carbonates found in different colored pigments or in paint fillers such as chalk, which can muddle the results.

“Taking from the side of the painting means you’re less likely to get a pure sample, which is why our technique is important,” says study coauthor Laura Hendriks, formerly a graduate student at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, Zurich. “The aim of the paper is to show that things can be less invasive.”

To get around the multiple carbonate problem, Hendriks decided to incinerate her samples and collect the resulting carbon dioxide for radiocarbon dating. Because lead carbonate degrades at 300 °C—a lower temperature than other carbonates—Hendriks figured that collecting CO2 at the correct temperature would isolate the carbon-14 needed to date the artwork accurately.

She tested the method on paint samples from the edges of paintings thought to be from the 1700s and on freshly prepared samples with known concentrations of carbonates, but the results didn’t agree. “Something wasn’t right,” she says.

It turned out that the paint in the fresh samples had more fatty acids from the oil in the paint, which dissipate as they age and react with other substances. These fatty acids interact with the carbonates during heating, distorting the data. Hendriks found that the solution was to remove the fatty acids via solvent extraction before burning. By doing that, she was able to validate the method for both the old and new samples.

Including the solvent extraction step is important even with samples from old paintings because a painting may have undergone undocumented conservation treatment. Materials added during a restoration could have different carbon-14 contents, Hendriks says. “Systematically using solvents removes any restoration material.”

“This is a very impressive result,” says Jaap Boon, an emeritus professor of analytical mass spectrometry at the University of Amsterdam whose research focused on the molecular material science of paintings.

Converting the level of carbon-14 measured into an actual year requires consulting a calibration chart of known historical atmospheric concentrations. For paintings made since the 1950s, it’s possible to be accurate within a year or two. For older paintings, it may only be possible to estimate age to within a few decades because CO2 levels did not change as quickly then and so are less distinct. Because of that, “this [method] will be more useful for detecting forgeries than giving precise dates for paintings with an unknown age,” Boon says.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter