Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Art & Artifacts

Oldest known plague victim found in museum collection

DNA extracted from 5,000 year old teeth push back origin of plague bacteria Yersinia pestis

by Laura Howes

June 30, 2021

When archaeologist Harald Lübke and colleagues excavated human remains from a site in Latvia, they sent the bones to Ben Krause-Kyora at Kiel University for genomic analysis to find out if the people buried at the site were related. They were not, but Krause-Kyora’s team instead found that one of the individuals was infected with Yersinia pestis, or plague. The remains were dated to 5,370-5,170 years ago, making the person the oldest victim of Y. pestis found to date, at least a hundred years before the previous earliest known case (Cell Rep. 2021, DOI: 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.109278).

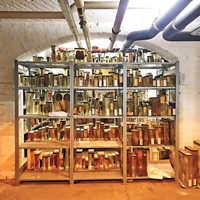

Around 5,000 years ago, at least four individuals were buried in a pit filled with shells and fish bones. In 1875, an amateur archaeologist dug up and studied the skeletal remains of two of them before sending them to a scientific society in Berlin, where they reemerged in 2011. A team of archaeologists recently returned to the same site and found the remains of two more individuals. They sent bones from all four individuals to Krause-Kyora for analysis.

The new plague genome was found in samples from an individual known as RV2039. The analysis revealed only that RV2039 was genetically male and died of plague between 20 and 30 years old.

Krause-Kyora’s team found evidence of Y. pestis inside the teeth of RV2039. Teeth are fantastic reservoirs of Y. pestis, says Kirsten Bos at the Max Planck Institute of Human History, who was not involved in the latest work. While people are alive, the teeth get a continual blood flow, she says, and then after death, the hard exterior can protect DNA for years and years. “It’s kind of like a little time capsule for the DNA,” she says.

Researchers know that Y. pestis split from a related bacteria, Y. pseudotuberculosis, many years ago. RV2039 has helped Krause-Kyora and colleagues push back the best estimates of when that divergence happened to approximately 7,000 years ago. And Krause-Kyora is convinced that while RV2039 is the oldest-known plague victim at the moment, eventually someone will find an even older victim. He now wants to try and screen more individuals to get a better picture of where Y. pestis existed long ago.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter