Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Art & Artifacts

Science reveals Rembrandt’s special paint recipe

Researchers decipher the chemical components that gave the Dutch master’s paintings texture

by Bethany Halford

January 10, 2019

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 97, Issue 2

This year marks the 350th anniversary of Rembrandt van Rijn’s death, but there is still much to learn about the Dutch master’s paintings. Now a team in Europe, led by Delft University of Technology’s Victor Gonzalez, reports the recipe Rembrandt used to create texture in certain portions of his paintings, a technique known as impasto, which involves applying thick layers of paint. The results reveal the chemical fingerprint of Rembrandt’s impasto, which could be used, along with other qualities, to authenticate Rembrandt’s work.

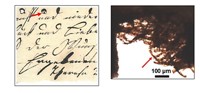

Gonzalez’s team used a combination of high-angle and high-lateral resolution X-ray diffraction to study several microscopic paint samples from four Rembrandt masterpieces spanning the artist’s career (Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, DOI: 10.1002/anie.201813105). In the impasto regions, they found the common pigment lead white, a mixture of cerussite (PbCO3) and hydrocerussite (Pb3(CO3)2(OH)2) that’s been used since antiquity. They also found something surprising, Gonzalez says: an unusual lead compound called plumbonacrite (Pb5(CO3)3O(OH)2).

The presence of plumbonacrite provides a new insight into how Rembrandt formulated his paints. Plumbonacrite probably formed over the course of centuries because Rembrandt likely used an alkaline binder with lead white to prepare his characteristic impastos. “Our best guess so far is that he used a litharge-based oil,” Gonzalez says. Litharge oil contains PbO, which makes it basic. In this alkaline environment, the paint could have reacted over time to form the plumbonacrite the researchers found.

“It is interesting that plumbonacrite was found in the impasto layer only,” says Rebecca Ploeger, an expert in art conservation science at Buffalo State who was not involved in the research. Litharge oil dries faster than many other binders, she says, and can therefore be used to quickly form impasto layers.

Next, Gonzalez and coworkers would like to expand their impasto studies to include more of Rembrandt’s work as well as paintings by his contemporaries to see if the plumbonacrite is specific to Rembrandt’s paintings.

The work “is an exciting next step into learning more about how Rembrandt, and possibly other artists, worked with and deliberately selected materials to achieve specific effects, such as impasto,” says Fiona T. Beckett, who teaches paintings conservation at Buffalo State. “Artistically, this makes perfect sense, and now there is additional scientific evidence to support this theory.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter