Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Imaging

Food dye makes tissue temporarily transparent

Tartrazine lets researchers peer beneath a live mouse’s skin to see its abdominal organs at work

by Bethany Halford

September 5, 2024

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 102, Issue 28

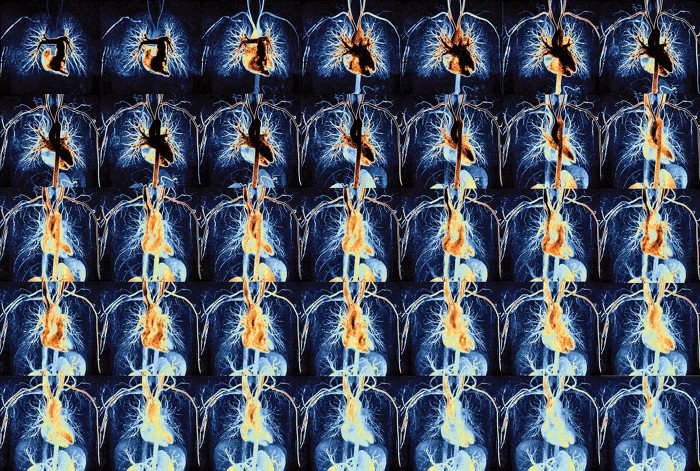

By applying a solution of tartrazine dye—a vibrant yellow food coloring—to a mouse’s skin, researchers were able to see through that opaque tissue. The transformation to transparency is temporary. A simple wash with water removes the dye and the effect. The technique, which has not been tested in people, could help biologists study living systems and might make some medical procedures less invasive.

A team led by Stanford University’s Mark L. Brongersma and Guosong Hong used light scattering to develop the technique. The refractive index of water in cells differs dramatically from the indexes of biological molecules like lipids and proteins. This variation makes light scatter and is one of the reasons that skin appears opaque. Tartrazine absorbs light in just the right region of the spectrum to change the refractive index of water so that it more closely matches those of biological molecules. This prevents light from scattering and makes it possible to see through tissue where the dye has been applied.

Zihao Ou, who is the paper’s first author and is now a professor at the University of Texas at Dallas, says the team first tested the dye on thin slices of chicken breast and watched them turn into what looked like a see-through jelly. To test the technique in a living system, the researchers applied tartrazine to the scalp of a mouse and saw cerebral blood vessels. They also used the dye along with a high-resolution microscope to investigate the microstructure of muscle in the mouse’s hindquarters. Finally, they spread the tartrazine on a mouse’s abdomen and were able watch its intestines move as the critter digested its most recent meal (Science 2024, DOI: 10.1126/science.adm6869).

“It changes how people think about live-animal experiments,” Ou says, because usually scientists remove the organs from animals they study. With this technique, he says, “we can directly look inside the body.”

“This approach offers a new means of visualizing the structure and activity of deep tissues and organs in vivo in a safe, temporary, and noninvasive manner,” write Imperial College London’s Christopher J. Rowlands and Jon Gorecki in a commentary on the paper (Science 2024, DOI: 10.1126/science.adr7935).

Ou says that there is much work to be done before the technique can be used in people. Human skin is at least 10 times as thick as mouse skin, and dark skin, which has higher levels of melanin, needs to be studied.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter