Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Policy

Sex and the Job Market

Job weakness may be a passing phase, but big changes for women in the workplace are here

by MICHAEL HEYLIN

March 8, 2004

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 82, Issue 10

The disturbingly sluggish rate of job creation during the economic recovery now under way for more than two years may turn out to be an aberration. It could just be an artifact of the working of the free enterprise system. The gains from the cost-saving actions of today, such as shipping more jobs overseas, will be invested in new endeavors that will generate a rush of new jobs for domestic workers tomorrow.

At least, that's what the current Administration and many economists believe. And that's what has happened in the past--if more quickly. The downsizings and restructurings triggered during and in the aftermath of a recession have formed the leaner, meaner base for the next round of economic expansion.

However, one does not have to be a worrywart to be somewhat apprehensive about short-term--or even mid-term--job prospects for working men and women in this country. Women have been notably less severely affected than men by the current job weakness, a possible augur of things to come as women progress toward becoming better educated than men.

According to government figures, the recession was mild and lasted only for the first three quarters of 2001. And the annual rate of growth of the gross domestic product surged to a spectacular 8% in the third quarter of last year, followed by a still healthy 4% in the fourth quarter.

The concern today is not that job creation is lagging during the early stages of an economic recovery. It always does. The issue is the extent to which it is lagging.

The number of people on nonfarm payrolls--generally accepted as the most reliable measure of employment--peaked at 132.5 million in March 2001. It was down 1 million by September 2001, the official end of the recession. When employment finally bottomed out in August 2003, it was down a further 1.7 million. Since then about 400,000 jobs have been regained.

This all means that in January there were still a substantial 2.3 million fewer payroll jobs than there had been 34 months earlier. And full recovery back up to the 2001 peak won't happen this year.

The resulting four-year or longer hiatus in job growth will leave a lasting mark on a nation with a workforce--those working plus those actively seeking work--growing by about 1 million per year and with an economy that had been generating more than 2 million jobs per year. The longest such hiatus previously had been 32 months in the early 1990s.

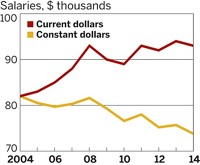

While workers may be paying less federal income tax these days, thanks to President George W. Bush's tax cuts, their salaries are stagnant in real terms. Also, they are facing higher education costs for their children, growing exposure to spiraling health costs, and increasing uncertainties about their pensions and future Social Security benefits.

Over the past 40 years, the percentage of those on payrolls who are women has risen inexorably from 37% to almost 49% today. But of the 2.7 million jobs lost between March 2001 and August 2003, only 600,000, or 21%, were lost by women, while 2.1 million, or 79%, were lost by men. This was largely because the bulk of the losses were in the manufacturing industry with its 70% male workforce.

A more pervasive vulnerability for men in the workforce as a group could be evolving from their relative turning away from higher education.

The 532,000 bachelor's degrees earned by men in 2001 were only 12% more than the 476,000 they had earned 30 years earlier. Over the same period, the number of women bachelor's graduates almost doubled from 364,000 to 712,000.

Put in different terms, women earned 43% of bachelor's degrees in 1971. They claimed 50% for the first time in 1982. They had 57% in 2001. And, according to the National Center for Education Statistics, they will earn 59% in 2112.

GROWTH FOR WOMEN is not confined to bachelor's degrees. They earned 40% of 1971 master's degrees and reached parity for the first time in 1981. They had 59% in 2001 and are projected to have 59% in 2112. For Ph.D.s, the trend is the same. But parity for women will take a while longer. Their share has increased from 14% of 1972 graduates to 45% of 2001 graduates. They also now earn about 45% of initial professional degrees in law and medicine.

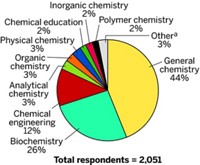

The preponderance of women at the crucial bachelor's-degree level is broad based. It cannot be explained away by the traditionally "female" disciplines, such as home economics, with 89% women. Women earned 50% of 2002 chemistry bachelor's degrees. Their share in other fields that year includes 61% for biological and life sciences, 54% for agricultural sciences, 50% for business administration, and 47% for mathematics.

An about 3-to-2 advantage for women in bachelor's-degree graduations--the entry point for higher degrees, the professions, better jobs, and a better life in general--is apparently here to stay. With 46% of college graduates working today being women, the trend is already moving through the workforce. And its economic and social implications will be profound.

I don't know what they will be. But they are fascinating to think about. Will women be able to fully exploit their learned skills in the workplace? How will men adjust to being less well credentialed than women? What will it mean for family life? Will men maintain an unduly large share of the good jobs anyway? Will they eventually return to higher education, at least to the same extent as women?

Views expressed on this page are those of the author and not necessarily those of ACS.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter