Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Business

Warming up to Global Warming

Chemical company views on greenhouse gas regulations are as diverse as the industry itself

by Alexander H. Tullo

February 9, 2004

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 82, Issue 6

Chemical companies generally walk in lockstep on issues like natural gas prices and railroad rates. However, companies' views on the regulation of greenhouse gas emissions are as varied as their product lines and home nations, largely because restrictions such as those in the Kyoto protocol would affect all of them differently.

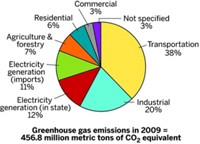

Greenhouse gases are a big deal for the chemical industry, if only because it emits a lot of them. Chemical makers account for about a fifth of the carbon dioxide emitted by U.S. manufacturers, and chemical companies worldwide are a major source of many other gases that are seen as contributing to global warming. The Kyoto protocol is an international agreement that calls for mandatory cuts from signatory developed nations in output of these gases from a 1990 baseline. Although the U.S. is a signatory to the treaty, it has never ratified it and thus is not bound by it.

The American Chemistry Council (ACC) has no stance on the Kyoto protocol. Spokesman Thomas Gilroy says the group didn't take a position--though it was part of the anti-Kyoto Global Climate Coalition--because it had to accommodate a lot of different opinions. "The membership is split," he says. "Every company is probably affected differently by Kyoto, so they all have their positions."

ACC also didn't support the Climate Stewardship Act of 2003, proposed by Sen. John McCain (R-Ariz.) and Sen. Joseph I. Lieberman (D-Conn.) and voted down in the Senate last year. The bill would have capped greenhouse gas emissions from the U.S. industrial, transportation, and power generation sectors at year 2000 levels by 2010.

Gilroy, however, says the industry does support the Bush Administration's proposal to reduce greenhouse gas intensity--emissions per unit of product--by 18%. ACC's own pledge is to reduce intensity 18% by 2012 from a 1990 baseline. ACC member companies must now report their progress toward the target as a condition of membership. The U.S. industry already has reduced greenhouse gas intensity by 12% since 1990.

Of ACC members, perhaps no company has been as outspoken against the Kyoto protocol as ExxonMobil. Late last month, the company paid for ads on the op-ed pages in the New York Times and the Washington Post in which it argued that "scientific uncertainties continue to limit our ability to make objective, qualitative determinations regarding the human role in recent climate change or the degree and consequences of future change."

THE NEED for more science has been ExxonMobil's mantra. But Brian Flannery, manager of science strategies in ExxonMobil's safety, health, and environment department, objects to the characterization that his company is in denial about the science. "We're engaged in the science," he says.

And, Flannery says, ExxonMobil acknowledges a risk to ecosystems because of greenhouse gas buildup. "We do believe there is a scientific case that there are actions that ought to be taken," he says. "On the other hand, it is clear we're facing a long-term issue and there are significant gaps in the science," such as the role of natural climate variability.

Flannery says the debate on climate change has centered too much on the Kyoto protocol, which he says is flawed because it is costly and ineffective in addressing risk, and because developing countries are not required to commit to emissions reductions. "Some say it is a first step; the question we have is, 'Is it an appropriate first step?'"

ExxonMobil is against greenhouse gas emissions caps, Flannery says, because they limit growth, but he acknowledges that this may not always be the case. "If in the future the science was more compelling, maybe--but it isn't today," he says. "And even then, one is going to have to find a way forward that is in some sense fair, affordable, and creates global participation."

Internally, the company's energy efficiency effort focuses on its refining and petrochemical operations. The highlight of this program, Flannery says, is cogeneration plants that produce both electricity and steam. At 30 facilities worldwide, ExxonMobil runs 80 cogeneration units that produce 2,900 MW of electricity. The company is planning another 1,000 MW of "cogen" capacity.

Other conservation projects such as reduced gas flaring in petrochemicals, fuel switching, and efficiency improvements that ExxonMobil has implemented so far have saved it $100 million annually. "Our goal is to make those emissions reductions when we can, but ones that are economical," Flannery says.

Dow Chemical, the largest U.S. chemical company, is neutral on the Kyoto protocol. But, in contrast with ExxonMobil, Dow does like some of its mechanisms, such as emissions credit trading, whereby companies that have cut emissions beyond government requirements can sell the excess to companies that haven't met limits, according to Peter Molinaro, leader of Dow's climate change team. Dow also supports "clean development" programs that would reward companies for projects that reduce emissions in developing countries by giving them emissions credits in developed ones that have reduction requirements under the Kyoto protocol.

Dow didn't support the McCain-Lieberman bill, Molinaro says, because it could help drive the high price for natural gas even higher. "A lot of the climate-change policies in this country rely on moving away from burning fossil fuels to renewable energy, but everybody knows that the transitional fuel is natural gas," he says. "And there isn't enough natural gas to do that without driving the chemical industry offshore."

Molinaro says Dow favors voluntary reduction programs over regulations. To this end, the company has so far decreased emissions of CO2 from 28.1 million metric tons in 1994 to 26.1 million metric tons in 2002.

Number two U.S. chemical company DuPont neither supports nor opposes the Kyoto protocol, but doesn't oppose greenhouse gas emissions regulations entirely, according to David K. Findlay, who recently retired as vice president of corporate development at DuPont Canada and helped lead DuPont's global efforts in climate change. He says DuPont even provided testimony to Congress on the McCain-Lieberman bill. The company is also a member of the Pew Center on Global Climate Change, which favors greenhouse gas reductions to supplement voluntary reductions by its members.

Findlay explains his company's rationale. "You can find today very articulate and very well-disciplined studies that call into question whether concentrations of CO2 are an issue or not," he says. "But you would also find many that would suggest that it is. From our perspective, there is enough valid scientific evidence to suggest that it is potentially an issue, and as a company, we need to take that into consideration when we think about our businesses."

"Every company is probably affected differently by Kyoto, so they all have their positions."

DUPONT'S EXPERIENCE in chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) in the late 1980s and early 1990s influenced its views on greenhouse gases, Findlay says. CFCs were ultimately phased out because of their effect on the ozone layer. "As the CFC issue built up, we let the science and the public opinion get ahead of our actions," he says. "As a consequence, when we accepted that the science was valid and we needed to do something, we incurred a fair bit of negative public opinion. We made a conscious shift in the early '90s to position ourselves ahead of the issues rather than reacting to them."

However, Findlay doesn't think the Kyoto approach to global warming is perfect, and developing countries will eventually have to be brought on board. "In future negotiations, those economies would have to be included and have the same sort of treatment as any other developed economy," he says.

DuPont already met a goal of reducing global greenhouse gas emissions 65% by 2010 from a 1990 baseline. So far, DuPont has taken steps such as reducing emissions of the greenhouse gas nitrous oxide from its adipic acid process and emissions of by-product hydrofluorocarbon HFC-23--trifluoromethane--from its fluorochemicals production. On the energy front, DuPont plans to hold energy use flat from 1990 through 2010. It also plans to source 10% of its global energy from renewable sources by 2010.

Other chemical companies that participate with DuPont in the Pew Center, such as Air Products & Chemicals and Rohm and Haas, have not endorsed the Kyoto protocol.

Air Products says it is concerned about climate change but believes the science is still evolving. Andrew J. Casale of the firm's energy and process industries group contends that any government regulations on greenhouse gases shouldn't interfere with business. "We believe progress can be made in addressing climate change and sustaining economic growth by adopting reasonable government policies and programs that do not impede the free market's ability to develop cost-effective solutions," he says.

Air Products' primary interest in the issue is in its products rather than the emissions it generates. "We are an enabler and provider of technology to develop more sustainable products for customers," Casale says. "Many of our industrial gases and chemicals businesses are geared toward making our customers 'green.' "

For example, Air Products won a 2002 Climate Protection Award from the Environmental Protection Agency for technology that reduces the amount of perfluorinated compounds emitted in semiconductor etching and cleaning. The company is also involved in programs that promote hydrogen as a future fuel.

Rohm and Haas is critical of the Kyoto treaty. "We are in the general camp that there were inherent flaws and problems with Kyoto that will hinder, rather than help, a goal of stabilizing atmospheric CO2 levels," says Ray Baker, manager of energy and utility systems at the firm's engineering and technical center. "We are strongly for voluntary action, and we're very strongly participating in ACC's voluntary commitment."

Because Rohm and Haas's interest in greenhouse gases is based solely on energy use in its plants, Baker says, its focus is on CO2 reduction. Unlike a firm such as DuPont, he notes, Rohm and Haas doesn't potentially have credits from other greenhouse gases such as hydrofluorocarbons that it can sell. "Some companies have a vested interest in selling credits," he says.

ROHM AND HAAS targeted energy intensity reduction of 5% at the time of its 1999 purchase of Morton International--and achieved it by the end of 2001. Half of the reduction, Baker says, came from its Houston plant, which, through fuel switching--namely, using its hydrogen off-gas stream as fuel--and other projects, was able to achieve a 23% reduction in energy use per pound of product since 1997.

With most of its production in Canada and a large part of its sales in the U.S., Nova Chemicals' main concern is competitiveness with the U.S., according to Gerry Finn, Nova's vice president of government and industrial relations. Hence, the company was against Canada's adoption of the Kyoto protocol. "If there are mandates in one jurisdiction and not in another, it can be enough to knock us out of a market or make us uncompetitive," he says. "We didn't like the idea because the U.S. wasn't going to ratify and there are other big jurisdictions around the world that weren't engaged."

Nova backs ACC's 18% intensity reduction goal, which the firm will roll out at its sites globally. "We support the idea of emissions per unit of output. It acknowledges there is going to be growth," Finn says.

Global competitiveness is on the minds of other firms from countries that have ratified the protocol. Germany's BASF, for example, says it strongly supports the Kyoto protocol and its "flexible mechanisms," but the company is concerned about the impact on the European Union.

"Our major criticism as an international company on the emissions trading system of the EU is that it will burden only European companies, as they will face additional production costs and investment risks," the company says in a statement. "This can result in severe disadvantages for production sites located in Europe." Instead, the company favors an emissions strategy that would be uniform worldwide.

According to the European Chemical Industry Council, chemical production in Europe has risen by 40% since 1990 while greenhouse gas emissions have fallen by more than 20%. Moreover, the chemical industry has already achieved about 30% of Europe's commitment to cut CO2 emissions equivalents by 336 million metric tons by 2012. BASF says regulation of the chemical industry isn't necessary, adding that "the emissions trading of the EU jeopardizes our voluntary self-commitment."

Advertisement

The companies that support voluntary efforts aren't bashful about saving money while reducing greenhouse intensity. ExxonMobil's Flannery notes that the focus on greenhouse gases has led to many profitable projects. "The attention and focus has helped to raise awareness," he says. "Some people confuse the fact that you are doing something economical with not doing anything."

Nova's Finn agrees. "Responding to a mandate is one thing," he says. But without them, he notes, "I don't think any company that has shareholders is going to be able to take actions that have no benefits other than reducing its emissions."

And some observers who support voluntary efforts note that looming rules may be a disincentive for work on greenhouse gas reductions. For example, a company may delay building a cogeneration plant until it is assured it will get the emissions credits. Others note that high energy costs in recent years have already created the incentive for conservation programs.

Despite a lot of concern from industry about how it will cope with greenhouse gas regulations, DuPont's Findlay has high praise for what the chemical industry has been able to achieve without them. "The chemical industry has really been, in a lot of cases, ahead of its time," he says. "If all companies had done as much as the chemical industry, this wouldn't be as big an issue as it is today."

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter