Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Environment

Protecting Ozone Helps Protect Climate

Reducing CFCs has a large impact on total greenhouse gases in the atmosphere

by BETTE HILEMAN, C&EN WASHINGTON

May 2, 2005

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 83, Issue 18

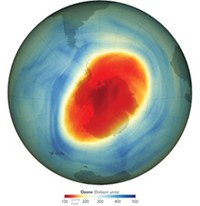

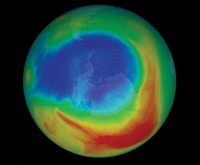

International efforts to protect stratospheric ozone by cutting back on emissions of chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) and other ozone-depleting chemicals have also helped protect the climate system, says a report from the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

The IPCC report presents the first comprehensive, quantitative estimates of how much the reduction of CFC emissions has contributed to mitigating the total amount of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. To further protect the climate, the report recommends that greater efforts be made to limit emissions of CFCs and those substitutes that have global warming potential.

It also points out that efforts to decrease the production of ozone-depleting chemicals have already had a successful outcome--levels of chlorine in the stratosphere have stabilized and may have started to decline.

Requested by the parties to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and to the Montreal Protocol on Substances That Deplete the Ozone Layer, the report was accepted at a UN meeting in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, by delegates from more than 100 countries on April 8. The summary was released on April 11, but the complete document will not be issued until sometime in May. This report represents the first cooperation between two environmental treaties.

The 1987 Montreal protocol committed countries to gradually phase out the production and consumption of CFCs and other chemicals that deplete stratospheric ozone and to replace them with compounds or processes that do not damage ozone.

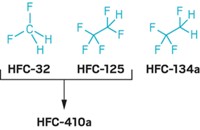

This reduction has had another beneficial effect. On a molecule-per-molecule basis, CFCs are much stronger greenhouse gases than carbon dioxide. Two of the major replacements--hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs) and hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs)--are also greenhouse gases, but their global warming potentials are generally much lower than CFCs'. So as HFCs and HCFCs have displaced CFCs in refrigerators, air conditioners, and insulating foams, the total amount of greenhouse gases contributed by these sectors has declined, the report says.

Emissions of CFCs, HCFCs, and HFCs in 1990 had the same global warming potential as 7.5 billion metric tons of CO2, the report explains. This was equal to about 33% of the 22 billion metric tons of CO2 produced by global fossil fuel burning in 1990. By 2000, emissions of CFCs, HCFCs, and HFCs had declined to the equivalent of about 2.5 billion metric tons of CO2. They are expected to fall still further to the equivalent of 2.3 billion tons of CO2 by 2015.

"The report shows the Montreal protocol has helped reduce climate change, but more could be done to reduce the impact of CFCs and substitutes," says Susan Solomon, a coauthor and senior scientist at the National Oceanographic & Atmospheric Administration's Aeronomy Laboratory.

THE REPORT suggests more could be done to decrease the global warming impact of CFCs and their substitutes more quickly. Application of so-called best management practices could cut the global warming potential of CFCs and their substitutes in half by 2015, it says. Some of these practices include improving the containment of CFCs and HFC substitutes in appliances such as refrigerators and air conditioners; recovering more of the substances at the end of the appliances' life or when CFC-containing foams are discarded; increasing the use of ammonia and hydrocarbons--which have no global warming potential--as refrigerants, especially in commercial units; and reducing the amounts of refrigerant used in each appliance.

Commercial refrigerators and freezers provide good opportunities for reducing emissions because they are large and tend to have more refrigerant leaks than appliances made for the home, Solomon says. Also, many, primarily older units, are still cooled with CFCs.

The report also draws attention to voluntary efforts to protect the climate. For example, the Mobile Air Conditioning Climate Protection Partnership, involving government, industry, and environmental groups, has pledged to reduce direct refrigerant greenhouse gas emissions by at least 50% and indirect greenhouse gas emissions from the fuel used to power vehicle air conditioners by at least 30%, with a global savings of billions of gallons of fuel.

One of the key messages of the report, Solomon says, involves the issue of "banks"--the CFCs, HFCs, and HCFCs that are stockpiled in currently used and discarded equipment and foam. For example, even though production of CFCs for use in developed nations has been mostly phased out, these compounds remain in old operating refrigerators and air conditioners and in discarded units.

"In the absence of a plan for not only stopping production of CFCs but actually managing what you have left at the time when you stop, you are going to get this material going to the atmosphere," Solomon says. For example, in terms of CO2 equivalents, about 16 billion metric tons of CFCs resides in the banks, and about 1.5 billion tons is being emitted to the atmosphere each year. Consequently, even without new CFC production, it would take 10 years to use up what is left in the banks, she says. Because of CFC banks and their high global warming potential, CFCs pretty much dominate emissions in the refrigeration and air-conditioning sectors, she explains.

And for substances like HFCs that are still being produced in high volume, if the leak rate is low, then more and more is being put in the banks each year--into existing and discarded equipment, Solomon explains. On a global basis, end-of-life recovery of CFCs, HFCs, and HCFCs is almost nonexistent, she says.

"This is the first UN report to show how large the banks are," says Stephen O. Andersen, a member of the steering committee that produced the report and director of strategic projects at the Environmental Protection Agency's Climate Protection Partnerships Division. "It also shows that, in some cases, these are either unwanted [no longer useful] chemicals or easily recoverable."

There are no incentives in the treaties to recover the compounds from discarded foam and equipment. "The Montreal protocol controls production but doesn't regulate use or recovery or destruction," Andersen says. The Kyoto protocol to the UNFCCC doesn't regulate ozone-depleting substances, even those with high global warming potential. "So there is no real incentive to reduce the greenhouse gas effect of uncontrolled CFCs already produced before the Montreal protocol phaseout," he says. "In the U.S., for example, we prevent the venting of refrigerants, but we don't offer a reward for recovery and recycling. So typically, CFCs just leak out and drift away from old refrigeration and air-conditioning equipment."

EVENTUALLY, when CFCs have been phased out in both developed and developing countries, Solomon says, it will be important to figure out what to do with the CFCs that have been recycled from old foam and equipment since there will be no uses for them. CFCs will have to be destroyed rather than collected and placed in stockpiles, she says. The Montreal protocol has approved a number of CFC destruction technologies.

"Both the Montreal protocol and the Kyoto protocol could learn from this report," Andersen says. "The Montreal protocol and the Kyoto protocol could do a better job if they were to cooperate. By cooperating, they could save money in protecting both ozone and climate."

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter