Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Pharmaceuticals

Design of an Antismoking Pill

The makers of varenicline got their inspiration from two natural products

by AMANDA YARNELL, C&EN WASHINGTON

June 6, 2005

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 83, Issue 23

More than two-thirds of the U.S.'s nearly 50 million smokers want to quit smoking--but only about 5% of those who try actually manage to kick the habit cold turkey, according to estimates from the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention. Pfizer is hoping that varenicline, a smoking-cessation agent now in late-stage Phase III clinical trials, could improve quitters' chances.

If approved, varenicline will join a market for smoking-cessation drugs that's currently dominated by nicotine replacement therapy. Patches, gums, nasal sprays, and inhalers help lessen smokers' cravings to light up by providing low levels of nicotine, the addictive ingredient in tobacco. The only nonnicotine antismoking medication currently on the market is GlaxoSmithKline's Zyban, a drug originally used to treat depression.

Varenicline, in contrast, "is the first nonnicotine antismoking medicine designed specifically to help smokers stop smoking," notes Jotham W. Coe, a research fellow at Pfizer. His team recently detailed the chemical logic behind the development of this molecule (J. Med. Chem. 2005, 48, 3474).

Addiction to nicotine is thought to stem from the molecule's ability to bind to a class of ion channels in the central nervous system. Called neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs), these channels normally bind the messenger molecule acetylcholine. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the part of the brain that responds to pleasurable or "reinforcing" stimuli--for instance, food, sex, drugs, or gambling--trigger the release of dopamine, a neurotransmitter associated with addiction.

Nicotine binds these same receptors to trigger dopamine release. Once smokers become dependent on the modest but pleasurable bursts of dopamine that accompany each drag on a cigarette, quitting smoking can be difficult.

"What we were after was a dopamine 'nightlight' that would be on at a low level until the smoker quit," Coe says. He and Pfizer chemists Eric P. Arnold, Paige R. Brooks, Michael G. Vetelino, and Brian T. O'Neill set about designing a molecule that would partially activate a particularly abundant nAChR subtype called  4β2. Like nicotine replacement therapies, such a molecule would reduce cravings and withdrawal symptoms by causing the release of a constant low level of dopamine, Coe says. "But importantly, we also wanted the molecule to block nicotine from binding" so that smokers wouldn't get any satisfaction from lighting up, he adds.

4β2. Like nicotine replacement therapies, such a molecule would reduce cravings and withdrawal symptoms by causing the release of a constant low level of dopamine, Coe says. "But importantly, we also wanted the molecule to block nicotine from binding" so that smokers wouldn't get any satisfaction from lighting up, he adds.

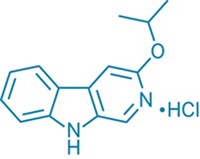

THE PFIZER TEAM first searched for compounds that might partially mimic nicotine's ability to activate a4b2. Their hunt turned up (-)-cytisine, a bicyclic plant alkaloid. A Bulgarian pharmaceutical company currently markets cytisine for smoking cessation. The drug has met with little success, however, presumably because it suffers from poor absorption and brain penetration properties, Coe hypothesizes.

In hopes of improving upon cytisine, the Pfizer researchers, led by O'Neill, devised a pair of practical synthetic routes to the alkaloid for medicinal chemistry studies (Org. Lett. 2000, 2, 4201 and 4205). They experimented with various derivatives, but these proved to be unworkable. Things began to look gloomy, until Coe--who had worked on morphine chemistry before joining Pfizer--made a pivotal observation.

Coe recognized that cytisine's structure is similar to that of the significantly larger alkaloid morphine, notes Craig A. Townsend, an organic chemistry professor at Johns Hopkins University. The two molecules' [3.3.1] bicyclic skeletons differ only by the position of a single nitrogen atom.

Organic chemists have spent lots of time and energy simplifying morphine while retaining the activity in the simplified versions, Townsend notes. Coe's team cleverly used this information to guide their attempts to simplify cytisine while maintaining its activity, Townsend points out. The result was a [3.2.1] bicyclic benzazapine that potently blocks nicotine binding to  4β2. Unfortunately, however, this simplified molecule lacks cytisine's ability to partially activate a4b2 and release low levels of dopamine. The team serendipitously restored this property by fusing heterocycles onto the benzazapine's aromatic ring via an unexpectedly regioselective dinitration reaction.

4β2. Unfortunately, however, this simplified molecule lacks cytisine's ability to partially activate a4b2 and release low levels of dopamine. The team serendipitously restored this property by fusing heterocycles onto the benzazapine's aromatic ring via an unexpectedly regioselective dinitration reaction.

One derivative, dubbed varenicline, has the best of both worlds: It partially activates  4β2 "to give some dopamine release so the person won't have so much craving," notes Susan Wonnacott, a neuroscience professor at the University of Bath, in England. "But at the same time, varenicline prevents nicotine from exerting any effect by blocking nicotine's access to these receptors," she adds.

4β2 "to give some dopamine release so the person won't have so much craving," notes Susan Wonnacott, a neuroscience professor at the University of Bath, in England. "But at the same time, varenicline prevents nicotine from exerting any effect by blocking nicotine's access to these receptors," she adds.

THE ORAL DRUG is well-tolerated, Coe notes. In clinical trials, about half of the smokers taking varenicline twice daily ceased smoking by the end of 12 weeks, compared with 12% of those on a placebo. These quit rates are roughly double those reported for Zyban, Coe tells C&EN. Late-stage Phase III studies now under way are examining whether varenicline helps smokers remain smoke-free in the long term.

If approved, varenicline is likely to face some stiff competition as drugmakers scramble to create products to help the world's 1.25 billion smokers kick the habit. Last month, Sanofi-Aventis asked the Food & Drug Administration to approve Acomplia for both obesity and smoking cessation. The drug, originally designed to help people lose weight, also curbs nicotine cravings (and presumably other types of cravings, too) by blocking the brain's endocannabinoid reward system. In addition, Nabi Biopharmaceuticals, Rockville, Md., and Zurich-based Cytos Biotechnology both have antinicotine vaccines in development. These vaccines are intended to eliminate the pleasure of smoking by sopping up the nicotine that smokers get from every drag, preventing it from ever reaching the brain.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter