Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Analytical Chemistry

Trapping Roaches with Biochemistry

Structure of an important cockroach pheromone is finally elucidated

by Bethany Halford

February 21, 2005

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 83, Issue 8

CHEMICAL SIGNALING

The chemical that makes a common household cockroach irresistible to her suitors may soon be used to create a new type of poisoned bait trap that can be used to kill nests of those same smitten insects. A group led by Wendell L. Roelofs, a professor of insect biochemistry at Cornell University, has deduced the structure of the sex pheromone that the female German cockroach, Blattella germanica, uses to attract potential mates [Science, 307, 1104 (2005)].

The simple 12-carbon pheromone--dubbed blattellaquinone by Roelofs and colleagues--has eluded natural products chemists for decades, according to Coby Schal, one of the report's coauthors and an entomologist at North Carolina State University. Entomologists didn't even realize it existed until 1993. Before then, they assumed that B. germanica didn't need a volatile sex pheromone because the cockroaches live in close quarters where males could easily find females, Schal says.

Getting enough of the pheromone to pin down its structure also proved to be a challenge: The compound is thermally unstable and is produced only in extremely small amounts by the female cockroach. It took more than 10 years and about 10,000 cockroaches, but the team was finally able to identify and purify the sex pheromone, thanks to a massive extraction effort and some specialized gas chromatography (GC) techniques.

To figure out which of the German cockroach's pheromones was responsible for long-range attraction, the team used a GC detector that's hooked up to a male cockroach. The instrument monitors his antennae's response to different compounds in the pheromone mix.

Once they knew which pheromone they were looking for, Schal's lab had the Herculean task of extracting enough material to characterize the compound. Extracts from about 5,000 female cockroaches ultimately gave 5 g of blattellaquinone. Satoshi Nojima, who was working in Roelofs' lab at the time, developed a special preparative GC technique to purify the thermally unstable molecule.

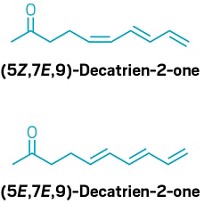

Roelofs' group employed standard characterization techniques to figure out the compound's chemical structure. They then synthesized the quinone and field-tested it at a cockroach-infested pig farm.

Despite their European moniker, German cockroaches infest homes and restaurants all over the world. If you've got a roach problem, it's usually a German cockroach problem, Roelofs says.

"This is a very important discovery for scientists," notes Philip G. Koehler, an entomology professor at the University of Florida who specializes in cockroach management. "The cockroach is known to be capable of transmitting disease, and allergic reactions to its shed skin and droppings are the most important causes of asthma in inner-city children."

The researchers have a patent pending on blattellaquinone, and several companies are interested in using the compound in their cockroach traps. These blattellaquinone-baited traps are likely to be more effective than food-baited traps, according to Koehler, because more roaches would be drawn by the pheromone. The tainted males would then return to the nest and poison it.

"The best control of this cockroach," Koehler says, "will be to use its own biology to defeat it."

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter