Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Environment

New Take on Dietary Habits of Ancient Life

September 17, 2007

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 85, Issue 38

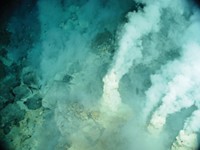

Hungry microorganisms in the primordial world may have relied on a scarcely explored process called sulfur disproportionation to stay well-fed (Science 2007, 317, 1534). Microbe menus can be pieced together to as far back as 2.7 billion years ago, but there's a dearth of earlier dining data. Some researchers have found evidence that ancient bacteria and archaea used sulfate reduction to sulfide as an energy source. Now, Pascal Philippot, a geochemist at the Institute of Earth Physics, in Paris, and international colleagues report that microorganisms from 3.5 billion years ago preferred elemental sulfur instead of sulfate. Employing sophisticated sulfur isotope analysis, the researchers conclude that microbes from remote Australia got their energy by enzymatically disproportionating sulfur—simultaneously reducing and oxidizing it—to hydrogen sulfide and sulfate. In a Science commentary, biogeochemist Bo Thamdrup of the University of Southern Denmark says the work provides a new piece for a microbial metabolism puzzle in which "most pieces are missing."

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter