Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Synthesis

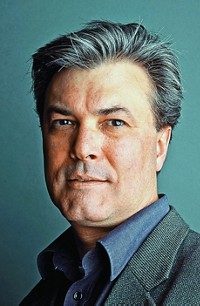

David W. C. MacMillan

February 12, 2007

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 85, Issue 7

David W. C. MacMillan entered college as a physics major but emerged as a chemist. When he was a first-year assistant professor, his research group at the University of California, Berkeley, coined the term "organocatalysis," denoting a new field in which he has been a pioneer and leader.

MacMillan, 38, is currently the A. Barton Hepburn Professor of Chemistry and director of the Merck Center for Catalysis at Princeton University. In the words of a colleague, MacMillan earned this award "for the development of new synthetic methods, especially those for the efficient synthesis of complex chiral molecules."

Organocatalysis employs small organic molecules rather than metal-containing complexes for enantioselective catalysis. MacMillan says he got the idea when he was a postdoc at Harvard University. He noticed that asymmetric catalysis was popular in academia but not in industry, and he suspected that using organic molecules as catalysts would provide the large-scale benefits that industry needed. And chemists could still study reactivity, selectivity, and mechanisms—"things that chemists love," he says.

"In his short career, MacMillan has developed new synthetic methods that have shown an unusual level of novelty and breadth of application. The reactions are based on fundamental chemical principles and are highlighted by their apparent simplicity and usefulness," says Robert H. Grubbs, a professor at California Institute of Technology and consultant for Materia.

Grubbs praises two specific advances from MacMillan's group. He classifies the first as a "spectacular synthesis of differentially protected carbohydrates in only two chemical steps." MacMillan's group devised a synthetic route for de novo synthesis of polyol-differentiated hexoses based on aldol coupling of three aldehydes with an organocatalyst (Science 2004, 305, 1752).

The second advance that Grubbs highlights is nicknamed "hydrogenation in a bottle." MacMillan describes this advance as "an incredibly operationally simple way of doing hydrogenation of electron-deficient olefins."

His group uses a powder source of hydrogen called Hantzsch esters. His catalyst is also a bench-stable powder. "We started to realize that maybe we could mix these two powders together," MacMillan says. Put a scoop of this blend into a reaction vessel and, essentially, the asymmetric catalytic hydrogenation is done, he says.

Materia has licensed MacMillan's imidazolidinone catalysts, and Aldrich recently commercialized the hydrogenation blend.

Born in Glasgow, Scotland, MacMillan received a B.Sc. in chemistry in 1991 from the University of Glasgow. He completed a Ph.D. in inorganic chemistry at UC Irvine in 1996 with Larry E. Overman. He did a postdoctoral fellowship with David A. Evans at Harvard.

In 1998, MacMillan joined the UC Berkeley faculty and rose through the ranks to full professor. He became the Earle C. Anthony Professor of Chemistry at Caltech in 2004. This past September, he moved his research group to Princeton. MacMillan also sits on editorial and scientific advisory boards and consults for several large pharmaceutical companies.

Among his awards, MacMillan received the E. J. Corey Award for Outstanding Contributions in Organic Synthesis by a Young Investigator in 2005 and a Camille & Henry Dreyfus Foundation Teacher-Scholar Award in 2003.

Does MacMillan have hobbies? "I like drinking," he says. But this chemist has never made beer.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter