Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Materials

Rocks Conduct Chemically

March 10, 2008

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 86, Issue 10

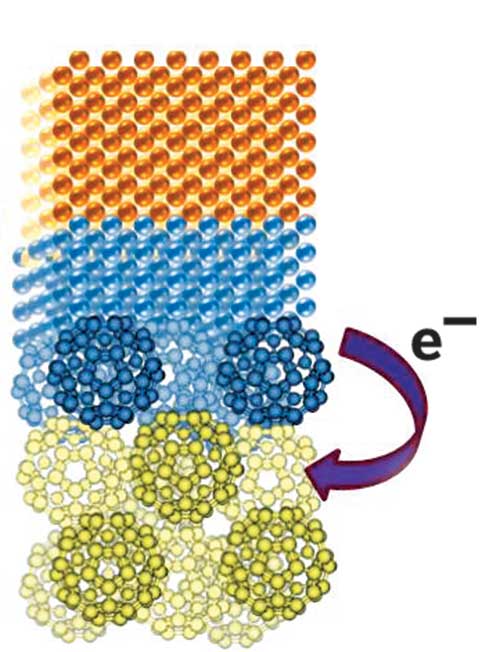

To determine the efficiency of treatments that remove iron(III) oxide rust, researchers typically measure the amount of water-soluble iron(II) that the treatments release. That kind of measurement doesn't tell the whole story, say Kevin M. Rosso and Svetlana V. Yanina of Pacific Northwest National Laboratory. They show that hematite, a naturally semiconducting iron(III) oxide, conducts electricity under certain chemical conditions without voltage application, thus enabling some soluble iron(II) to be recycled as iron(III) deposits (Science, DOI: 10.1126/science.1154833). Hematite's different crystal surfaces have varied microstructures, each with different chemical functionalities that dictate whether it can conduct electricity. The team made millimeter-sized hematite cubes with these different microstructures exposed on each face. Under reducing conditions, most microstructures dissolved away as iron(II), as expected. On one type of microstructure, however, pyramid-shaped iron(III) deposits grew. Pyramids appeared only when the arrangement of microstructures allowed electrons to flow, and the researchers conclude that the reduction process triggers current flow.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter