Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Environment

Inadvertent Contamination

Flame retardants are seeping from research bases into Antarctica's pristine environment

by Sarah Everts

February 4, 2008

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 86, Issue 5

A PRELIMINARY INVESTIGATION of wastewater sludge and dust samples from U.S. and New Zealand research bases in Antarctica reveals unexpectedly high concentrations of polluting flame retardants, at levels comparable with those in U.S. urban centers.

"I was shocked by the findings," comments Cynthia de Wit, an environmental toxicologist at Stockholm University who was not involved with the research. "It shows that small communities such as research bases in remote, so-called pristine areas can be significant point sources for polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs)."

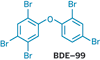

PBDEs have been used for decades to prevent furniture upholstery, electronics, and carpets from catching fire.

Toxicologists worry about accumulation of PBDEs in organisms because the molecules are structurally similar to thyroxine, a hormone critical in fetal development. Lab experiments also indicate that some PBDEs, namely pentabrominated congeners, can interfere with early neurodevelopment.

After measuring high levels of PBDEs in wastewater sludge and dust from two Antarctic bases—the U.S.-operated McMurdo base and the New Zealand-operated Scott base—Robert C. Hale of the Virginia Institute of Marine Science and his colleagues checked whether the pollutants had seeped into the local ecosystem. Their preliminary measurements reveal a PBDE concentration of 2 ppm in fish and aquatic invertebrates near the bases (Environ. Sci. Technol., DOI: 10.1021/es702547a). These levels rival those found in fauna near North American cities.

Jules Blais, director of the chemical and environmental toxicology program at the University of Ottawa, says that he is convinced the measured PBDEs near the research bases are derived mainly from local sources, rather than from long-range atmospheric transport.

Although U.S. manufacturers agreed to phase out two families of bioaccumulative PBDEs, known as penta-BDEs and octa-BDEs, in 2004, penta-BDEs such as BDE-99 were the most abundant species in the samples near the McMurdo base.

The more than 80 research bases in Antarctica probably haven't updated most of their furniture or electronics since 2004, Hale says.

In light of his team's findings, Hale argues that current rules for treating wastewater in the Antarctic should be revised. In particular, the Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty does not oblige research bases to install wastewater treatment plants on-site. The treaty requires large bases to macerate their wastewater sludge prior to discharge so that it decomposes faster. But maceration doesn't prevent PBDE release from sludge into the environment.

In 2003, the huge, 1,200-person McMurdo base did install a sophisticated waste-treatment facility that reduces the release of pollutants, including PBDEs. So the bulk of the PBDEs measured was probably released prior to 2003, Hale says. McMurdo's wastewater treatment system is only one of a few in Antarctica. Many other smaller bases still only macerate their biowastes, if that, he notes.

Hale worries that other chemicals from personal care products and pharmaceuticals, such as estrogens, may also be escaping into the Antarctic ecosystem. His team is currently making further measurements of both PBDEs and estrogen-like molecules near the research bases.

"It's ironic that our presence in Antarctica, even for the purpose of environmental research, can lead to pollution of this very same environment," Hale tells C&EN.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter