Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Synthesis

Stripping Staph Of its 'Golden Armor'

February 18, 2008

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 86, Issue 7

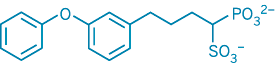

More people die from drug-resistant staph infections in the U.S. than from HIV/AIDS, so finding new antistaph strategies is an important research goal. Eric Oldfield at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, and colleagues have now identified such an approach by potently inhibiting formation of the golden pigment staphyloxanthin in Staphylococcus aureus, increasing the bacterium's susceptibility to attack by the human immune system (Science, DOI: 10.1126/science.1153018). They find that three phosphonosulfonate compounds disable the enzyme that makes dehydrosqualene, the first step to the pigment. One of the three phosphonosulfonates (shown) has been tested in human clinical trials as a cholesterol-lowering drug. For that application, it targets human squalene synthase, which catalyzes the initial step to cholesterol and is structurally similar to the enzyme target in S. aureus. Staph cells treated with the inhibitor grow white and become susceptible to attack by reactive oxygen species, a key tactic of the immune system's defense. Dosing mice with the inhibitor reduced bacterial counts 50-fold. In essence, the inhibitor strips staph of its "golden armor," Oldfield says.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter