Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Safety

Plant Blast Rekindles Dust Debate

Need for tougher combustible dust controls is likely to be examined in light of deadly blast

by Jeff Johnson

February 25, 2008

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 86, Issue 8

THE MASSIVE LETHAL explosion in a dusty sugar plant in Georgia earlier this month has reopened debates on how to reduce the likelihood of explosions due to combustible dust, hundreds of which have occurred over the past three decades.

Dust explosions unfold in waves, says Daniel A. Crowl, professor of chemical process safety at Michigan Technological University. The rapid-fire explosions can roll through a plant—a moving fireball of flames and violence. The initial blast might not be a dust explosion at all. Even static electricity can set it off.

"But the first explosion can stir up the dust that has settled in the plant over the years, lying on the floor, on beams, above suspended ceilings, in tiles," Crowl explains. "That dust is disturbed by the explosion, is thrown into the air, mixes with oxygen, and is ignited by the first explosion."

And on it goes, Crowl says. More explosions occur as the combustible dust is disturbed and entrained in air and ignition moves through the plant.

Subsequent explosions are often larger than the first, he says, and they can blast through a factory, traveling along conveyor systems, and in pneumatic transfer lines, ducts and vents, and tunnels. The same passages needed to move products, workers, or equipment become chimneys of fire.

Indeed, the first few of nine workers killed at the Feb. 7 Imperial Sugar Co. explosion were found in tunnels that run under the plant floor. Last week, the smoldering fires at the sugar refinery cooled enough to allow accident investigators onto the Port Wentworth site, outside of Savannah. In the weeks ahead, investigators will stir through the rubble and ashes, gather data, and interview survivors. And all of that information will likely lead to a further debate between two federal agencies—the Chemical Safety & Hazard Investigation Board (CSB) and the Occupational Safety & Health Administration (OSHA)—over how the wide range of plants, including chemical companies, that generate combustible dust should be regulated.

"What people often don't understand is that a lot of solid material, when finely divided into a dust form, becomes highly explosive. And I mean really highly explosive," Crowl says.

SIZE MATTERS. Usually, the smaller the combustible particle, the more surface area is available relative to weight-less energy is needed to set the particle on fire, and it will burn faster. Experts say combustible material of 420 ??m or less should be considered explosive.

"The problem is that plants have huge quantities of this stuff, and people don't think of it as explosive. I mean, who would think that sugar is explosive? You use it all the time," Crowl points out.

But if you are moving sugar around in a processing plant, particles get broken down from mechanical handling, and they collect, unnoticed, on all manner of surfaces. Then, all it takes to trigger a conflagration is something as simple as a spark.

"We are not talking about a fog of dust here," Crowl says. "One-eighth of an inch along the floor is enough," he notes. "I've been in factories where one-half inch of dust coats the floor."

Combustible dust is part and parcel of a variety of industries, among them chemicals, plastics, rubber products, iron, aluminum, wood, grains, and sugar. A CSB accident survey found 20% of all combustible dust accidents were in the chemicals, plastics, and rubber industrial sectors.

No one knows yet how much dust was at the Imperial Sugar plant when it blew up, and no one is sure what caused the triggering explosion. Investigations expect to determine that in the weeks and months ahead (C&EN, Feb. 18, page 5).

The lead investigatory body for this kind of accident is CSB, a federal agency responsible for investigating chemical accidents and searching out their root causes. It has all too much experience with dust explosions, notes Daniel Horowitz, a CSB spokesman.

The board's interest in combustible dust was first raised in 2003 when three separate dust accidents killed a total of 14 workers, injured 77, and destroyed the plants. The industries were unrelated but all generated combustible dust, according to CSB reports.

ONE OF THESE accidents involved West Pharmaceutical Services, which produced rubber syringe plungers at a plant in Kinston, N.C. Rubber strips were dipped into a slurry of polyethylene, water, and surfactant to cool and coat the rubber. The plant's visible production area was extremely clean, but unknown to plant personnel, polyethylene powder had accumulated on surfaces above the suspended ceiling, providing fuel for a devastating secondary explosion. The plant had been inspected by OSHA, local fire officials, and insurance underwriters. None had identified the potential for a dust explosion that killed six workers, injured dozens, and destroyed the plant on Jan. 29, 2003.

Another accident took place at CTA Acoustics in Corbin, Ky., which manufactured acoustic insulation for automobiles. On the day of the explosion, Feb. 20, 2003, a curing oven had been left open, igniting combustible resin dust stirred up by workers cleaning the area near the oven. Management was aware of the hazards associated with the dust, but they didn't take steps to stop the dust from accumulating throughout the production area, particularly in ducting and quite expectedly in dust-collecting systems. The plant had been inspected by the Kentucky office that oversees OSHA compliance but was not cited for dust hazards. Seven workers were killed, 37 were injured, and the facility was destroyed.

The third accident was at Hayes Lemmerz International in Huntington, Ind., which made cast aluminum alloy wheels. Scrap aluminum was chopped up and moved pneumatically to a scrap-processing system, where it was dried and fed into a furnace. The explosion on Oct. 29, 2003, originated in the dust-collector system and spread through ducting, causing a huge fireball to emerge from the furnace. The plant had been inspected by Indiana OSHA, which found no dust problems. One worker was killed and two were injured.

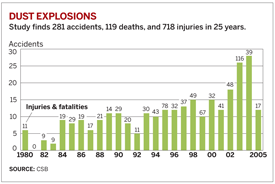

On the basis of these accidents, CSB began a review of dust accidents that occurred between 1980 and 2005. It identified 281 combustible dust incidents that killed 119 workers and injured 718, as well as extensively damaging the facility. Injuries or deaths occurred in 71% of the accidents.

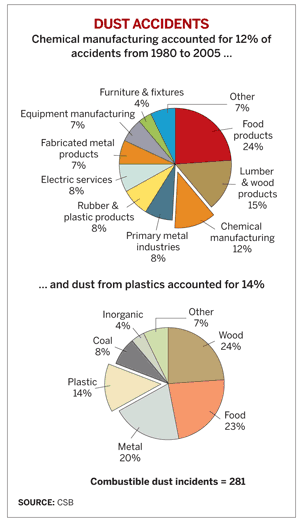

The study did not examine grain-handling facilities or coal mines, because they are already regulated by OSHA or other federal agencies. The food-processing and lumber industries had the largest share of accidents, but chemical manufacturing accounted for 12%, and rubber and plastics companies made up 8% of the incidents.

In November 2006, CSB made a series of recommendations based on the report and their investigations.

"Combustible dust fires and explosions are devastating, preventable, and often fatal tragedies," warned former CSB chairman Carolyn W. Merritt at the November release. "Dust explosions often cause loss of life and terrible economic consequences. While some programs to mitigate dust hazards exist at the state and local levels, they form a patchwork of adapted and adopted voluntary standards that are challenging to enforce. New federal standards are necessary to prevent further loss of life."

CSB has no regulatory authority, but OSHA does. Hence, the board recommended that OSHA issue a general comprehensive dust standard to become part of its inspection protocols to address hazard assessment, engineering controls, housekeeping, and worker training for a wide range of chemical, rubber, metal-processing, plastics, and food-processing companies that generate combustible dust. The general standard would be similar to OSHA regulations for the grain industry, Horowitz notes.

CSB wanted OSHA to regulate all companies that generate combustible dust in the same way it chose to regulate grain-handling facilities, Horowitz explains. OSHA instituted regulations for grain facilities in 1987, following a series of accidents in the late 1970s and early 1980s. In December 1977, five grain elevators exploded, killing 59 workers and injuring 49.

As the new standards went into place, grain dust explosions rapidly fell. In a 2003 report, OSHA heralded this success, saying injuries due to grain explosions had decreased by 55% and deaths by 70%. OSHA's report estimated that the standard had prevented 9.4 deaths per year. It also found that the standard had had no significant economic impact on small businesses.

AS AN INTERIM measure, CSB urged OSHA to implement a "special emphasis inspection program" for industries at particular risk for dust explosions, including plastics, pharmaceuticals, aluminum casting, and wood products industries.

However, OSHA did not follow CSB's recommendation for a general combustible dust regulation. Instead, it held back and instituted a national emphasis program, similar to what CSB had recommended as an interim step.

"The CSB report is a good report," says Richard E. Fairfax, OSHA director of enforcement programs. "But we didn't feel there was enough information in it for us to go on and make a determination for a general combustible dust standard."

OSHA had already begun a trial program for dust using its emphasis approach in the Philadelphia region when CSB released its recommendations, Fairfax says, and it had decided to expand that program nationally. So far OSHA has conducted 39 inspections and issued a few violations under the program, he says. OSHA will continue to expand the program over the next six months to a year and gauge its success.

"We haven't gone out and rejected the board's recommendations," Fairfax asserts. "After we run this national emphasis program for a while, we will pull back and look at what we are citing and what we are finding. We will make a recommendation to the assistant secretary of labor that says we need to go forward, or we won't if we think we already have it covered," he says.

However, even as CSB conducted its investigation and prepared its report, it heard from OSHA state inspectors who urged the board to recommend to OSHA that it establish a national standard to give inspectors clear authority to act on dust violations. Fairfax acknowledges that it is more difficult to enforce violations under the emphasis program than under a regulatory program such as that for grain facilities, but he says a combination of various provisions already on the books may give inspectors enough authority to take actions that can reduce accidents.

Whether the Georgia blasts will trigger pressure that leads to a general dust regulation is yet to be seen. "It is too early to know yet," Fairfax says, since inspectors are just entering the site.

Crowl predicts it is likely that the sugar explosion will kick up concern over dust accidents. "Clearly, accidents are happening and people are not doing things properly.

"These explosions are entirely preventable," Crowl says. "It is not like we don't understand dust and how to handle it properly. Good housekeeping is the primary way to clean it up, along with getting management to pay attention. People don't want to blow up their own plants, but you have to have the right technical information and resources as well as oversight and management systems in place to make sure it doesn't happen."

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter