Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Pharmaceuticals

Weighing Options

In the wake of drug-trial setbacks, obesity researchers assess what it will take to move forward

by Carmen Drahl

April 13, 2009

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 87, Issue 15

THE SEARCH for a simultaneously effective and safe medication for obesity is a quintessentially modern endeavor, but it involves tackling challenges rooted deep in the past—in prehistory, actually.

Human feeding behaviors have evolved over millions of years, and early humans lived in a world where calories weren't always easy to come by. "Cavemen who had the ability to store lots of energy as fat had a much better likelihood of surviving. It could be a long time between killing woolly mammoths," quips John McElroy, president and chief scientific officer of Jenrin Discovery, a privately held company working on obesity drugs.

That prehistoric legacy has led to problems, because cheap and alluring food abounds in today's more sedentary culture. Obesity is reaching epidemic proportions. According to the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention, in some parts of the U.S., more than 30% of the population is obese. Obesity is defined as having a body mass index greater than 30, which is a measure of weight in relation to height and approximates levels of body fat.

But treating obesity isn't just about getting in shape for swimsuit season. Obesity contributes to rising health care costs because of other conditions that go along with it. "Being overweight is one thing—it's the consequences of being overweight that are the problem," says Roger Hickling, research and development director of Alizyme, a U.K.-based company that has obesity drugs in development.

For instance, obesity is a risk factor for metabolic syndrome, which can lead to cardiovascular disease and diabetes. Physicians have learned that losing even a modest amount of weight can lessen an obese person's risk of such diseases.

Treatments for obesity have developed along several lines, encompassing the diet, exercise, and surgical options such as gastric bypass procedures, as well as pharmaceuticals. Although there are several Food & Drug Administration-approved agents for treating obesity, many obese patients don't use them because they have side effects, including high blood pressure and flatulence.

Efforts to develop new weight-loss medications have been littered with dashed expectations. Last fall, for example, several pharmaceutical companies halted development of obesity drug candidates that blocked the cannabinoid 1 receptor (CB1), which is also a target of marijuana's primary psychoactive ingredient, tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). Only a few years earlier, drugs in the CB1 class had been hailed as potential blockbusters (C&EN, Nov. 22, 2004, page 83). Researchers ultimately couldn't find a way around the drugs' psychiatric side effects, such as depression and anxiety, in a small percentage of patients.

The CB1 story is a reminder that researchers still don't fully comprehend the mechanisms behind obesity, despite the billions of dollars spent on research, according to experts who spoke with C&EN. Nonetheless, the community is learning from the CB1 candidates' legacy and is optimistic that some therapeutic compounds remaining in the pipeline will become successful drugs or at least advance the understanding of obesity.

IN THE EARLY 1990S, researchers uncovered telling details about how the brain controls food intake and how it communicates with the gut. Those and other findings eventually led to drug development for several new targets, including neuropeptides, intestinal hormones, and the CB1 receptor, explains Thomas Hughes, a nutritional biochemist who is president and chief executive officer of Zafgen, a privately held company that is developing novel obesity drugs that block the nutrient supply to fatty tissue.

"What tends to happen in drug discovery is that waves of products come along from many companies at once," which was the case with CB1 blockers, Hughes says.

Researchers at Sanofi-Synthelabo, now part of Sanofi-Aventis, generated a great deal of excitement with their first-in-class CB1 blocker, rimonabant, says Randy J. Seeley, a psychiatry professor and associate director of the Obesity Research Center at the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine. "When Sanofi showed good efficacy in their original Phase II clinical trial results, everybody and their mother set out to make a best-in-class CB1 blocker," he says.

"Just about every pharmaceutical company had a horse in that race," agrees Donna Ryan, a physician and associate executive director for clinical research at Pennington Biomedical Research Center, a hub for obesity research located in Baton Rouge, La.

On the basis of the available data, CB1 drug candidates generally produced modest but clinically relevant weight loss in obese patients, says Ryan, who has advised several companies developing obesity medications, including Sanofi-Aventis, Merck & Co., Vivus, and Arena Pharmaceuticals. More important, researchers had reason to believe the compounds, independent of their weight-loss effects, also had positive effects on known indicators of diabetes, although that was never definitively confirmed, Ryan notes. Rimonabant was approved for treating obesity in Europe in 2006, but it didn't gain approval in the U.S.

As waves of drug candidates progress through the pipeline, sometimes a couple of them become medicines, and sometimes the entire wave fizzles, Hughes says. Some information about CB1 blockers' psychiatric side effects trickled in from late-stage trial data and regulatory agency documents, but the CB1 wave really receded in late 2008. In October, the European Medicines Agency recommended a temporary suspension of rimonabant sales in Europe, concluding that the drug's benefits no longer outweighed its risks. "The problem was that if you gave a dose low enough to avoid adverse effects, you didn't have enough efficacy to meet requirements," Ryan says.

In November 2008, Sanofi decided to discontinue all ongoing rimonabant clinical studies, says Elizabeth Schupp Baxter, director of the company's U.S. communications. "Sanofi took this decision in light of recent demands by certain national health authorities," she says. Mood disorders and suicides have been reported in patients taking rimonabant, Baxter says, but a causal relationship with the drug has not been formally established.

After Sanofi's decision, "it was almost like dominoes—these candidates started falling one at a time," says Jenrin's McElroy. For instance, Merck terminated development of its CB1 receptor blocker taranabant, which had reached Phase III trials, and Pfizer ended Phase III trials of its own CB1 blocker and exited from research in the obesity area entirely (C&EN, Feb. 23, page 38). Some companies exiting the CB1 area cited the tough regulatory climate as a key reason for stopping their programs.

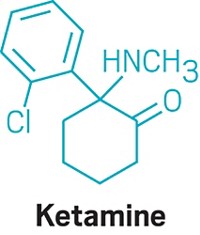

"IF YOU SMOKE marijuana, you feel euphoria and you get the munchies," says Frank Greenway, a physician and obesity researcher at Pennington, referring to THC's effect on CB1 pathways. "It shouldn't be a big surprise" that CB1 receptor blockers depress moods and appetites in some patients, since rimonabant and other drugs in its class block the receptors that THC activates, he says. Greenway has worked as a consultant for several companies developing obesity drugs, including Sanofi and Orexigen Therapeutics.

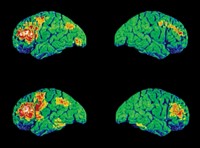

Generalizations aside, the microanatomic location of drug action could also have been a factor in the side-effect profile, says Seeley, who advises a number of companies developing obesity drugs, including Zafgen. CB1 receptors are abundant in the hypothalamus, a communications nexus in the brain that is a control center for many things, including appetite. With the benefit of hindsight, the fact that CB1 receptors can be found at varying levels throughout the brain, and not only in the hypothalamus, could explain why the drugs affected some pathways that weren't intended, he adds.

"Compared to other metabolic diseases, such as type 2 diabetes, the molecular mechanisms of obesity are not well understood," says Nancy Thornberry, vice president and worldwide basic research head for diabetes and obesity at Merck. "Our understanding of the neural pathways that contribute to feeding behavior is in its infancy."

At the molecular level, researchers have a good idea of what receptors drugs hit, Seeley notes. "But going from there to how they exert their effects in the brain can be quite murky," he adds.

Some researchers believe CB1 drugs could find a new lease on life as peripherally acting drugs, which don't enter the brain at all, thus potentially avoiding psychiatric side effects.

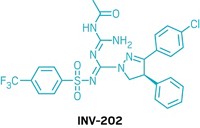

Keeping drugs out of the brain is the guiding philosophy at Jenrin, McElroy says. Beginning three years ago, chemists at Jenrin systematically modified the structures of certain CB1-targeted drug candidates. The team sought molecules that would no longer enter the brain but that would act at peripheral CB1 receptors, which are in metabolically relevant tissues such as liver, muscle, fat, and the digestive tract. At the same time, the company's medicinal chemists attempted to retain favorable properties such as target selectivity and the ability to be taken orally.

When given orally to obese mice, two of the redesigned CB1-blocking compounds lowered body weight and showed signs of lowering the risk for diabetes and heart disease, according to results presented at the Obesity Society's 2008 scientific meeting. Jenrin's molecules aren't ready to be tested in humans, however. McElroy estimates that Jenrin is 12 to 18 months away from having a compound that's ready for Phase I clinical trials.

Merck's Thornberry concurs that peripherally acting CB1 drugs are a possible way forward, and she notes that another option might be developing CB1 drugs with different binding properties. CB1 receptors carry out many functions in the brain, some of which require natural binding partners, or ligands. Through in vitro binding studies, researchers learned that rimonabant and Merck's taranabant were inverse agonists, she says. Inverse agonists block a range of receptor functions, including some that don't require the binding of natural ligands to take place. It would be interesting to instead study a neutral CB1 antagonist, a molecule that can block only ligand-binding-dependent events, Thornberry says.

CB1 receptors are not the only receptors in the brain that are involved in obesity. The obesity drug pipeline is vast and encompasses biopharmaceuticals and small molecules, many of which target non-CB1 pathways in the brain.

Orexigen, for instance, has two potential small-molecule obesity therapies that act on the brain and are in late-stage clinical trials. Contrave, the candidate that is further along in the pipeline, is a combination therapy containing bupropion, an antidepressant and smoking-cessation aid that boosts dopamine signaling, and naltrexone, an antiaddiction drug that targets opioid receptors. Both components are already FDA-approved and have established safety records.

Orexigen chose this combination on the basis of an in vitro model of a specific region in the hypothalamus, says Dennis Kim, an endocrinologist and Orexigen's senior vice president of corporate development. Bupropion is thought to boost release of a hormone, melanocyte-stimulating hormone, that acts within the hypothalamus to reduce appetite and increase metabolic rate. "In isolation, that sounds like a good pathway to target," Kim says. Unfortunately, the pathway is subject to a negative feedback loop that's thought to be involved in resisting long-term weight loss. Naltrexone was chosen as a complement to bupropion in order to block those compensating mechanisms.

Some patients taking Contrave in early-stage clinical trials developed nausea, but Orexigen has since developed proprietary sustained-release formulations of both active ingredients, which they believe will alleviate that side effect.

Results from one Phase III trial of Contrave were released in January 2009. Patients who took Contrave combined with diet and exercise counseling lost more body weight over one year than a placebo group on a diet and exercise regimen alone, without increases in depression or related side effects. Furthermore, patients on Contrave also saw improvements in certain markers that indicate cardiovascular risks.

"It's not just about helping patients lose weight—if you're not helping them improve health risks overall, then the treatment is much less meaningful," Kim says.

Orexigen expects to release data from three additional Phase III trials on Contrave this summer. The company is also conducting Phase IIb trials on Empatic, a different combination therapy for obesity.

THE RATIONALE behind combination therapies such as Contrave and Empatic has its roots in the prehistoric origins of human feeding behavior, Kim explains. The negative feedback loop that Contrave targets is just one of many pathways that have evolved over time. "Evolution has caused our bodies to err on the side of having too many mechanisms for having a high drive to eat food," he says. "Obesity is so complex and so multifactorial that it's hard to find a silver bullet."

Wesley W. Day, a clinical pharmacologist and vice president of clinical development at Vivus, agrees. "Feeding behavior is supported by diverse mechanisms—block one, and others come into play," he says.

Advertisement

Vivus' combination therapy, Qnexa, was developed by Thomas Najarian, former medical director and vice president of Interneuron Pharmaceuticals, today part of Endo Pharmaceuticals. Like Contrave and Empatic, Qnexa is a combination of FDA-approved drugs. Qnexa combines phentermine, a stimulant that boosts metabolic rate and energy expenditure, and topiramate, an antiseizure medication that has been shown to promote weight loss mainly by enhancing feelings of fullness.

Topiramate targets several different receptors in the brain, and although some of the targets are related to feeding behavior, the complete pathway through which topiramate exerts its weight-loss effects is not clear, Day notes. "We're very interested in fully understanding the mechanisms of action. Figuring out exactly how our combination works will be important for developing the next generation of agents," Day says. What's most interesting about Qnexa is that it is still effective for weight loss at very low doses, about one-fourth to one-eighth of the dose normally given for the drugs on their own, Day adds.

Results from a Phase III trial of Qnexa were released in December 2008. Patients in the trial who combined Qnexa with a diet and exercise regimen had a statistically significant difference in weight loss compared with a placebo group, with minimal reports of depression or related side effects. Vivus plans to report data from its other two Phase III trials in the coming months.

AT THE END of the day, obesity drug candidates have to obtain FDA approval. It's not certain that the drugs now in the pipeline will pass muster, because beyond efficacy, FDA also weighs specific numerical weight-loss benchmarks. Orexigen and Arena, which also has an obesity drug in Phase III trials, both disappointed investors this year when their candidates met some but not all of those benchmarks in initial Phase III results.

The CB1 story has made it clear that FDA has a very high bar for safety, especially since most of the drugs must be taken long- term, Kim says. "It's difficult to argue that more weight loss justifies a lower hurdle for safety" for an obesity drug candidate, he adds.

One reason the bar is so high is that, despite safeguards, there will be a certain amount of cosmetic use for any obesity drug, Pennington's Greenway says. Another is that it's more challenging to weigh safety concerns for an obesity drug, where the lifesaving benefits may not be as immediately apparent as for a cancer or HIV medication, Seeley says. "We know that people are dying because they're obese—but they don't die tomorrow, and they don't die of obesity, per se," he says.

Researchers developing obesity drugs must continually be mindful of the interconnectedness and complexity of the systems involved, Zafgen's Hughes says. "Obesity is an area with a lot of unanswered questions," he says.

One way to unearth new obesity drug targets is through genetics studies, Merck's Thornberry says. Many institutions are conducting research to that end, including Merck, which recently published genetics studies in both mice and patients, conducted in collaboration with multiple institutions (Nature 2008, 452, 423 and 429).

And the age-old issue of food and pleasure is part of the equation. It's an open question whether researchers will ultimately be able to dissociate the pleasurable effects of feeding behavior from the pleasurable aspects of other activities in the brain, Thornberry adds. Merck is pursuing animal models that may have predictive value for assessing psychiatric side effects early in drug development. "Obesity is a major unmet need—it's crucial to continue research in this area," she says.

And there's plenty of research ahead. When it comes to the biology behind obesity, Kim says, "I think we're just scratching the surface."

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter