Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Materials

A New Zip For Nanoribbons

New methods peel open carbon nanotubes lengthwise to give strips of graphene

by Mitch Jacoby

April 20, 2009

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 87, Issue 16

TWO TEAMS of researchers working independently report in Nature a new strategy for forming graphene nanoribbons: by longitudinally "unzipping" carbon nanotubes (2009, 458, 872 and 877). Compared with other procedures for preparing graphene nanoribbons, which are narrow and elongated one-atom-thick strips of carbon, the new routes are simpler, less expensive, and potentially better suited to making bulk quantities of the material.

A host of recent studies have shown that sheets of graphene are endowed with properties that may make the material useful for future nanoscale electronic devices (C&EN, March 2, page 14). Graphene nanoribbons may be especially useful because in ribbon form, the material's electronic classification—metallic or semiconductor—is tied to its width and the smoothness of its edges. For that reason, researchers are developing simple ways of producing large quantities of graphene nanoribbons with controlled properties.

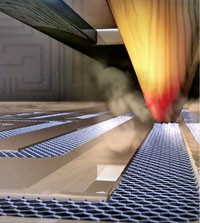

In the present studies, both teams unzip or cut the nanotubes along their axes to convert the elongated cylinders into flat strips. But the groups differ in the way they unzip the tubes. Rice University chemists Dmitry V. Kosynkin, Amanda L. Higginbotham, James M. Tour, and coworkers treat the nanotubes with sulfuric acid and potassium permanganate. The process unzips multiwalled and single-walled tubes chemically and forms ribbons measuring up to a few micrometers in length and a few nanometers to hundreds of nanometers in width. The researchers follow the oxidizing procedure with chemical reduction to restore the material's electrical conductivity.

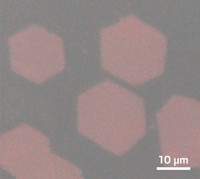

The other team, which includes Stanford University chemists Liying Jiao, Li Zhang, Hongjie Dai, and coworkers, partially embeds the nanotubes in a polymer film to hold them in place and then etches them with an argon plasma. They remove the film with solvent vapor and heat. This process also unzips multiwalled and single-walled nanotubes and yields graphene ribbons 10–20 nm wide.

At this early stage in the methods' development, the Rice group notes that their technique works well when applied to multiwalled nanotubes and tubes with multiple surface defects, as produced, for example, by chemical vapor deposition. Unzipping single-walled tubes, however, leads to narrow but entangled ribbons, they say. The group is now finding ways to untangle the products. The Stanford technique is especially useful for unzipping narrow and highly crystalline tubes.

In an accompanying commentary in Nature, Mauricio Terrones of the Institute for Scientific & Technological Research, in San Luis Potosi, Mexico, remarks that the studies "break new ground in bulk fabrication of nanoribbons." He adds, however, that more work is still needed to learn how to control the widths and edge patterns—and hence the electronic properties—of these flattened and unzipped tubes.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter