Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Materials

Mussels Cling With Iron-Clad Complexes

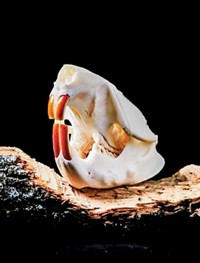

Iron-dopa crosslinks give byssal thread cuticles hardness and extensibility

by Bethany Halford

March 8, 2010

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 88, Issue 10

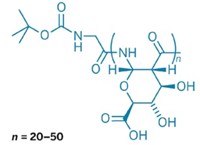

In the rough-and-tumble ocean environment, mussels sure show some muscle. Despite crashing waves, these mighty mollusks manage to stay put, thanks to the energy-dissipating byssal threads they use to lash themselves to rocks and other surfaces. Much of these threads’ staying power comes from their outer cuticle, a biological polymer that’s hard and resists abrasion. Now, a team led by Matthew J. Harrington of Max Planck Institute, in Potsdam, Germany, has used in situ resonance Raman spectroscopy to study the byssal cuticle (Science, DOI: 10.1126/science.1181044). The team’s results provide the first direct evidence that the cuticle is a proteinaceous polymeric scaffold stabilized by complexes of iron and the catecholic amino acid 3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine, or dopa, which is present in one of the cuticle’s proteins. When dopa complexes with iron, it crosslinks the proteins. The density of these iron-clad complexes varies throughout the cuticle, Harrington’s team found. Areas rich in the crosslinks give the cuticle hardness, whereas less crosslinked regions provide extensibility. It’s “an ideal coating for compliant substrates,” the researchers note.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter