Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Business

Petrochemicals

North American producers are bracing for long-anticipated capacity to come on-line in the Middle East and Asia

by Alexander H. Tullo

March 15, 2010

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 88, Issue 11

One might expect North American petrochemical makers to be despondent over the imminent arrival of new production capacity in Asia and the Middle East. They aren’t. Although 2009 started with the recession in full swing, the year ended surprisingly strongly as low feedstock prices made the region a competitive place to manufacture ethylene and its derivatives.

These petrochemical makers realize as they begin 2010 that the day will soon come when the world market is much more amply supplied. But between recovering domestic demand and the expectation that low feedstock costs are here for a while, observers point to a possibility that the effects of the new capacity may be blunted in North America. Europe, with higher costs and closer proximity to the new capacity, might not be so lucky.

Overall, 2009 ended on a pleasant note for U.S. petrochemical makers. According to the American Chemistry Council, the U.S. chemical industry’s main trade organization, combined U.S. production of polyethylene, polypropylene, polyvinyl chloride, and polystyrene inched up 0.9% in 2009, hitting 33 million metric tons. The year before, output fell nearly 12.3%. Ethylene makers posted a modest, less than 1% increase in 2009 production to 22.7 million metric tons, according to statistics from the National Petrochemical & Refiners Association (NPRA).

Dan Carlson, general manager for lower olefins for the Americas at Shell Chemicals, says 2009 was like two very different years rolled into one. “The first half was an absolute disaster,” he says. “In the second half, there was certainly a significant recovery. Asia is the driver for economic recovery right now. And U.S. exports are really fueling the surge in demand that we have seen for monomers.”

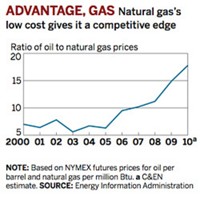

Low natural gas prices have been the salvation for the North American industry. Even through a harsh winter, they have been about $5.00 per million Btu, whereas oil prices have been about $80 per barrel, a 1:16 ratio. Based on energy content—a barrel of oil contains about 6 million Btu—the ratio should be about 1:6. The biggest contributor to the imbalance has been the burgeoning supply of natural gas from shale, made possible by advances such as horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing of rock formations (C&EN, Sept. 21, 2009, page 26).

The price imbalance has created an advantage for U.S. chemical producers, which overwhelmingly run natural-gas-derived feedstocks—the so-called lighter raw materials known as natural gas liquids—through their steam cracking units to make ethylene. Producers in Europe and Asia tend to use “heavy” oil-based raw materials such as naphtha, and they are facing high costs of production.

These days, U.S. producers of ethylene derivatives are exporting 20% or more of what they make. LyondellBasell Industries recently reported that it is exporting about 30% of its U.S. polyethylene production, split evenly between Asia and Latin America.

Nine years ago, during the last chemical industry trough, U.S. exports were hit hard. In addition to an economic recession, that downturn featured overbuilding of production capacity at home and natural gas costs that exceeded those of oil.

John Stekla, director of ethylene studies at the Houston-based market research group Chemical Market Associates Inc. (CMAI), says 2009 offered a strong contrast. “Natural gas and ethane prices stayed very low,” he says. “There was strong demand from China for exports due to the local stimulus package. The low-cost competition from the Middle East projects was very slow to come on. With all of these factors, it was a surprisingly good year.”

The ethylene value chain is a lot more profitable now than it was back then, Stekla says. In 2001, cash profit margins for ethylene were about 4 cents per lb, whereas polyethylene margins barely rose above breakeven. Last year, ethylene earned slightly less than 4 cents, but polyethylene profitability shattered records, yielding margins for the entire chain of nearly 20 cents. The reason, he explains, is that naphtha-based petrochemical complexes in Asia are setting the standard for polyethylene prices.

Depending on its original design, a typical ethylene cracker can take in a range of feedstocks but usually requires capital investment to extend its feed capabilities. Owing to the price incentive, North American petrochemical makers are lightening the feedstock slates as much as their equipment will allow. In 2009, 83% of U.S. ethylene production was derived from natural gas liquids, estimates Gregg Goodnight, principal of Pearland, Texas-based ChemAnalysis. In 2008, based on industry data, the number was about 75%.

Pétromont, a joint venture between Dow Chemical and Société Générale de Financement du Quebec that closed in 2008, was the last naphtha-only cracker in North America, Stekla says. “There are no pure naphtha crackers left. They have either been shut down or they have developed the ability to crack a lighter feedstock slate,” he says.

The shift to lighter feedstocks does have consequences. As the U.S. industry relies increasingly on ethane to make ethylene, it will churn out less coproduct propylene. According to NPRA, propylene production from U.S. ethylene crackers declined 15% in 2009 versus 2008.

In addition, oil refinery operating rates have been slumping, leading to less by-product propylene from that source, Goodnight notes. Refineries put out 7% less propylene in 2009, NPRA figures indicate.

Goodnight says higher values for coproducts such as propylene could lead to equilibrium between heavy and light feedstock use. “Heavies have become more competitive with light cracking in the first quarter,” he says. “These things always swing back and forth.”

Oil and natural gas pricing will eventually come back into balance, acknowledges Grant Thomson, president of olefins and feedstocks for Nova Chemicals, but not anytime soon. Apart from chemicals and heating, oil and natural gas are used for very different things: mostly transportation for the former and power generation for the latter. “For the next three to five years, we are going to continue to be long in gas and tight in crude,” he says.

Given the trend, it’s not surprising that chemical makers are investing in upgrades that allow them to crack even more light feedstocks. Shell has projects under way at its crackers in Norco, La., and Deer Park, Texas, to better integrate those facilities with its nearby refineries and also enable them to crack more light feedstocks. The projects mostly entail investments in logistics to handle the different materials coming in and out of the plants.

So far, the company has been able to increase its use of light feedstocks to about 70% of its slate, and it is planning to push that number even higher. In 2003, when heavy feedstocks were advantaged over ethane, Shell was cracking about 75% heavy feedstocks, Carlson says. “Nothing stays constant in this business,” he notes. “You have to continually reinvent how you make money in olefins.”

Indeed, other chemical producers have rolled out similar projects. For example, this year, LyondellBasell, which has traditionally relied on heavy feedstocks, plans to complete a project meant to enable its Corpus Christi, Texas, ethylene complex to crack lighter feeds.

Nova wants to tap directly into the new gas from shale. The company recently signed a memorandum of understanding with the pipeline firm Buckeye Partners to evaluate shipping natural gas liquids from Pennsylvania’s Marcellus basin to its petrochemical complex in Sarnia, Ontario (C&EN, Feb. 22, page 19). Thomson explains that the natural gas from Marcellus has turned out to be richer in ethane than previously thought. “Certainly there are enough liquids to make it economical to extract them,” he says.

T. J. Wojnar, senior vice president of polymers at ExxonMobil Chemical, points out that the company hasn’t needed to invest more in feedstock flexibility because its ethylene crackers are already highly integrated with its refineries. ExxonMobil is prepared for a continued gas advantage or an eventual swing back in favor of oil. “It isn’t about any particular feed,” Wojnar says. “It is about the ability to run a broad range of feeds, depending on what the economics drive you to do. Having all the feeds available within our own refining infrastructure is certainly a big asset.”

No matter what their feedstock needs are, petrochemical producers the world over are facing a downturn because a massive number of new plants will open over the next 12 to 18 months in Asia and the Middle East. These plants threaten to push production capacity far in excess of demand, reducing operating rates industry-wide and even leading to plant shutdowns.

ChemAnalysis’ Goodnight expects global ethylene capacity to increase by 8.3% in 2010, another 4.5% in 2011, and an average of 3.0% in each of the three years after. Meanwhile, he points out, demand for ethylene grows by only about 4.5% in an average year. Without major plant closures, global operating rates, which are expected to average about 82% in 2010, will remain below 85% through 2015, he says. The ethylene industry considers itself healthy when operating rates are above 90%.

“This is a cyclical business; it always has been, and it will continue to be,” Shell’s Carlson says. But executives originally expected the onslaught of supply years ago, and the project delays have benefited the industry. “When capacity gets delayed, it gives markets a little more time to grow and be in position to absorb the capacity,” he says.

Nova’s Thomson agrees. He acknowledges that the Middle East capacity will displace some North American exports to Asia. “That might not be the worst thing, seeing that we haven’t had many capacity additions here in North America,” he reasons. “We are going to need some of those volumes that are now being exported.”

In particular, Carlson notes, exports to Asia will likely wane just as domestic sectors such as housing and auto manufacturing begin to pick up again. And with the low natural gas prices, it’s possible that North America might not lose the entire export market after all. “Our low natural gas position suggests U.S. exports are not as vulnerable as we would have thought a year or two ago,” Carlson says.

The North American industry has done a good job of bracing for the downturn, CMAI’s Stekla observes, cutting about 3 million metric tons of annual ethylene production capacity over the past three years out of 35.4 million metric tons. Notable closures include Pétromont; Lyondell’s Chocolate Bayou, Texas, cracker; a Dow Chemical cracker in Hahnville, La.; Flint Hills Resources’ cracker in Odessa, Texas; and some of Eastman Chemical’s capacity in Longview, Texas. “The market has taken some aggressive steps to ensure its future competitiveness,” he says.

In addition, Stekla says ethylene plants lose some of their throughput capacity when they convert to lighter feedstocks. “We don’t think we need to shut down any additional capacity past the shutdowns we have seen so far,” he says. “That puts North America where it needs to be going forward.”

European petrochemical makers might not be so lucky. In a January conference call with financial analysts, LyondellBasell’s chief executive officer, James Gallogly, noted a sharp difference between the company’s U.S. and European results for 2009. In the U.S., ethylene profit margins declined by 26% while polyethylene margins increased by about 6%. In Europe, ethylene margins plummeted 89% while polyethylene declined 5%.

“Europe stands out as the most impacted region,” Gallogly said. “European crackers did not benefit from the low ethane prices and the derivative export opportunities that supported U.S. results.”

Mark Garrett, CEO of Austrian olefins and polyolefins maker Borealis, expects a modest increase in imports of Middle Eastern polyethylene into Europe over the next few years. In addition, lower cost resins will make Asia-manufactured plastic goods cheaper, squeezing the customers of European polymer makers.

“The increased availability of this cost-competitive material from the Middle East to both the Asian and European markets will put pressure on operating rates for local producers and pressure to reduce costs,” Garrett says. “Hence, there may be some units in both regions that will find it difficult to remain profitable and, as a result, capacity may be closed.”

In a recent report, the consulting firm KPMG warned that the capacity in Asia and the Middle East could render 14 out of 43 European ethylene crackers uneconomical by 2015. Together, these facilities put out about 26% of the continent’s ethylene. KPMG cautioned that the U.S. could be similarly impacted.

Advertisement

ExxonMobil’s Wojnar emphasizes that in downturns driven by oversupply, closures can occur anywhere high-cost capacity is found. But Goodnight notes that other factors can go into the decision to close plants. For instance, a small, aging Chinese or European cracker might seem like a good candidate for closure, but customer relationships or a local government could be keeping the facility open.

A company can also be reluctant if it doesn’t have another ethylene plant. He notes that most of the plant closures seen so far have come from large firms such as LyondellBasell and Dow with global supply chains and the luxury of shuttering capacity and running the rest of their plants at higher rates.

Such factors, Goodnight says, might make a big difference in determining how much capacity is ultimately closed in the coming trough. “If we continue with mediocre or lousy margins but companies aren’t bleeding red, then I think the tendency will be that the marginal crackers will just hang on,” he says. The result would be a mild but prolonged downturn. “If things get really bad, then it may help the industry recover more quickly.”

Nova’s Thomson hopes that the coming years will turn out better than the most pessimistic predictions. “They used to say that by 2005 and 2006 there would be no exports coming out of North America,” he says. “We sit here in 2010 and just finished a record year of exports out of North America. I have always said, and always believed, that the impact wasn’t going to be as soon and wasn’t going to be as great as what people were forecasting, and I still believe that.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter