Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Environment

Marine Life

by Rudy M. Baum

April 12, 2010

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 88, Issue 15

AS SOME OF YOU may remember from a previous column, my wife, Jan, and I took up scuba diving three years ago. It was kind of a lark at the time, but both of us have since become passionate divers. The week before last, we spent a week diving on Little Cayman in the British West Indies.

My first dive instructor, Len Clark, admonished his class not to even think about taking a camera under water until we had at least 50 dives under our belts. "You won't take any good pictures," he said. "You won't have any fun. And perhaps most important, nobody who's diving with you will have any fun, either."

I took Len at his word. It took me about 50 dives before I was even able to think about anything much more than the fact that I was breathing under water and what my dive computer was telling me about how much air I had left in my tank. On a trip last summer to Grand Cayman, however, I took a basic underwater photography rig—good-quality Canon point-and-shoot camera, waterproof box, and Ikelite strobe flash attachment—and the results were not bad.

I include on this page four of the better photos I took at Little Cayman. In a week or so, we'll have a slide show of some more photos on the Editor's Blog on "CENtral Science."

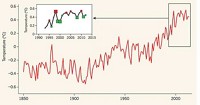

The creatures on the reefs around Little Cayman are protected because they live in marine national preserves. They are threatened by global climate change, of course, which is lowering the pH of seawater and, with it, the integrity of the reefs themselves.

Other ocean creatures face more immediate and lethal threats. In mid-March, delegates at a United Nations conference on endangered species voted down a U.S.-sponsored proposal to ban international trade in bluefin tuna, largely at the behest of the Japanese government. Japan consumes about 80% of the bluefin tuna catch, much of which is caught in the Atlantic Ocean.

The bluefin tuna is a magnificent marine creature, possibly warm-blooded, that is spiraling toward extinction because of the predatory fishing practices that are used to meet Japanese demand for the fish. Estimates suggest that the bluefin population in the Atlantic has dropped by as much as 80% since 1970. The vote against the ban was a shameful capitulation to an utterly unsustainable practice.

Thanks for reading.

Rudy Baum

Editor-in-chief

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter