Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Environment

Battling The Bedbug Epidemic

Chemical controls, government action, and personal vigilance are all required to tame the outbreak

by William G. Schulz

March 7, 2011

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 89, Issue 10

Bedbugs, an ancient scourge of humanity, have returned to become a national nightmare. Their stunning worldwide resurgence, public health experts say, is creating a wake of human misery, financial wreckage, and toxic hazards that few wish to contemplate given the level of disgust most people have for the topic.

In acknowledgment of the growing epidemic, the Environmental Protection Agency and the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention have issued a joint statement on bedbugs, noting their “alarming resurgence” and calling them a pest of “significant public health importance.” Chemistry, these agencies and many bedbug experts say, is essential in efforts to control the outbreak.

Last month in Washington, D.C., EPA held its second National Bed Bug Summit, a visible effort to gather experts in a search for solutions, as well as to address public concerns and the need for accurate information about bedbugs and their control. EPA has also developed a highly praised comprehensive website about bedbugs.

But for many frontline workers, statements, meetings, information sheets, and websites are not enough. They fault EPA in particular for avoiding more direct actions—such as granting permission to use more effective pesticides that have been withdrawn from the market—that could help them get rid of bedbugs and protect people from other serious health and safety problems that have emerged in relation to the crisis.

“There’s lots of pressure on federal agencies, but they have not done very much,” says Dini Miller, an associate professor of entomology at Virginia Polytechnic Institute & State University who has become one of the leading authorities on bedbugs. Part of the problem, she says, is that it is not clear which agency—housing, health, agriculture, or environment—has authority for any given aspect of the problem. “Bedbugs don’t fall under anybody’s mission, so they have fallen through the cracks,” she says.

When bedbugs invade, they take hold in mattresses, box springs, chairs, nightstands—any sleeping area—emerging at night to take a blood meal from their human hosts. Entomologists say bedbugs likely sense CO2, body heat, other bodily emanations, or some combination of these that draw them to their target. Because the insects are stealthy, infestations are often not detected until they have become massively severe.

Although bedbugs are not officially considered a disease vector, they can exact a steep physical, emotional, and financial toll: Their bites can trigger severe allergic reactions. When people find out they have bedbugs, health care workers say, they often suffer severe mental anguish and find sleep impossible.

Professional extermination can cost thousands of dollars and take eight weeks or more. Many over-the-counter products kill the insects only on contact, pest control experts say, leaving behind reinforcements.

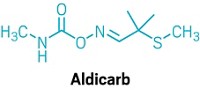

In the mid-20th century, bedbugs were nearly wiped off the planet with the help of powerful chemicals such as DDT and organophosphate, carbamate, and pyrethroid compounds, to name a few. No one advocates bringing back unsafe pesticides that were banned for good reasons, but experts say regulators must acknowledge that only a very limited number of effective pesticides—mainly pyrethroids—remain to treat infestations. Besides, they say, bedbugs now show resistance to many of the older chemistries, including DDT.

The search is on both in industry and academe for new compounds to fight bedbugs that are safe and effective. It is a race against the clock as the insects increasingly show resistance to chemicals that are in use.

But chemicals must be used strategically and with caution, says Department of Agriculture entomologist Mark F. Feldlaufer, who studies bedbugs and possible chemical means of control. “Different approaches depend on different situations,” he says. “Where they are found may dictate the type of treatment. Chemicals are part of that approach, but only part,” he notes, adding that the wrong chemicals in the wrong place can simply prompt the insects to scatter, only to return at a later time.

“Everyone is searching for a silver bullet,” Feldlaufer says. “But if the silver bullet is a chemical,” the insects will likely develop resistance.

The resistance problem is vexing, says entomologist Kyle Jordan, a BASF market development specialist who works with academic and other researchers seeking new chemical technologies to deal with bedbugs. Even in one neighborhood, the bedbugs can all be different in terms of resistance, he says. “It’s not like one person gets the same strain as everyone else.”

One new compound on the market is the pesticide chlorfenapyr, marketed as Phantom. Developed by BASF, the halogenated pyrrole can rapidly knock down infestations, Jordan says, and provide the residual kill that can prevent resurgence of infestations.

Many factors contribute to the bedbug resurgence, but “no one can say there’s not a direct relationship with the reduction in available organophosphate, pyrethroid, and other compounds,” says Jay Vroom, president of CropLife America, an industry group for makers of agricultural chemicals, some once used as indoor pesticides but now restricted. The chemicals pose risks, he says, but they also offer benefits: They kill bugs, rapidly and effectively.

“We have a pretty impressive arsenal of chemistries to deal with other pests,” says Michael F. Potter, a professor of entomology at the University of Kentucky and an urban pest control expert. “But the arsenal is just really depleted for bedbugs.”

With fewer effective solutions, government officials have been scrambling to respond to the rapid spread of infestations nationwide. They say the insects are becoming increasingly difficult and costly to contain, often overwhelming public health agencies with already-strained budgets. They emphasize that the most vulnerable people in society—many immigrants, the poor, the homeless, and the elderly—stand to become permanent victims of an out-of-control problem.

The state of Ohio has become bedbug ground zero, says Ohio General Assemblyman Dale Mallory of Cincinnati. He says the state is gripped by an epidemic now also taking hold nationwide. From a trickle of infestations first reported in the Cincinnati area in 2004, Ohio’s bedbugs have spread like wildfire up through Dayton, Columbus, and beyond.

“Bedbugs are in every zip code. They are all over the state,” says Susan C. Jones, an associate professor of entomology at Ohio State University and an urban pest expert. She says reports of infestations in public housing, apartment buildings, hotels, movie theatres, retail stores, schools, and health care facilities continue to skyrocket. State officials say the costs of treating infestations, as well as the loss of business for retailers and others, have been profound.

“The impact of these infestations has been most significant in lower socioeconomic areas where the cost of treatment and lack of information puts safe and effective control out of reach for many residents,” reads a report released in January by the Ohio Health Department’s Bed Bug Workgroup. Lacking resources, most local health departments “are unable to provide even minimal attention to prevent infestations from growing and spreading to other areas,” the report continues.

“We have incapacitated seniors being eaten alive in their beds,” Mallory says. In Cincinnati public housing, he says, “it’s a never-ending battle for control.

“I have toured apartments infested with bedbugs and nearly gotten sick,” Mallory says. In such heavy infestations, he says, the blackened trails of bedbug fecal matter are readily visible. “When you step on the bugs, you can see the blood.” He says some of his constituents have resorted to sleeping and spending their days in plastic chairs to keep the bugs away.

The economic costs are enormous, Mallory says. “People are throwing everything they had away.” An apartment complex in his district spent nearly $200,000 trying to get rid of an infestation, he says. “Who has that kind of money?”

The people of Ohio need help, Mallory says. “The excuses have run out.”

Mallory and other Ohio state officials have turned to EPA for help. They have pleaded with the agency for an emergency exemption to use the carbamate pesticide propoxur, which is one of the few compounds proven to quickly knock back infestations and provide long-lasting residual kill. But they say it has been an uphill struggle against agency bureaucrats, including EPA Administrator Lisa P. Jackson.

Propoxur was removed from the market beginning in 2007, when EPA demanded safety and efficacy data that producers determined were too costly to develop. Now, only existing stocks of propoxur—rapidly dwindling—are available for use, and only by professional exterminators.

Ohio and 18 other states first requested EPA’s permission for emergency indoor use of propoxur in October 2009. Ohio officials hoped to open up new supply lines and treatment modes for products with the active ingredient, allowing them to tackle resilient infestations in places such as housing facilities for the elderly, homeless shelters, and public housing.

But by April 2010, when EPA had yet to respond to Ohio’s request, then-governor Ted Strickland wrote personally to Jackson. “Reinstating the residential use of propoxur on a limited basis is necessary because of the insects’ resistance to currently approved pesticide products,” he wrote. “Without the use of propoxur, there is very little that can be done to meaningfully stop the spread of bedbug infestations.”

Jackson denied Ohio’s request, writing that “propoxur, along with other members of its chemical class, is known to cause nervous system effects. The Agency’s health review for its use on bedbugs suggests that children entering and using rooms that have been treated may be at risk of experiencing nervous system effects.” She went on to note that the agency is pursuing many activities regarding bedbugs, including meetings with “experts and stakeholders nationwide to determine what other pesticides may be effective for bedbug control.”

“I appreciate that EPA is meeting with experts and stakeholders,” Strickland fired back, “but fear the damage that may be done by the time an acceptable treatment is discovered.”

An EPA spokesman contacted by C&EN insisted that the agency did not deny Ohio’s request but offered no further explanation. A request for the agency to respond to other criticisms concerning the bedbug issue has gone unanswered as of C&EN’s press time.

Mallory and others have vowed to fight EPA and Jackson over the use of propoxur. He says he is introducing legislation in the Ohio General Assembly in that regard.

A member of Ohio’s congressional delegation, Rep. Jean Schmidt (R), also plans to take up the matter. “We intend to hold EPA’s feet to the fire,” a spokesman for Schmidt says.

“I want to make sure that EPA regulations—particularly those affecting the eradication of bedbugs—are based on science and are not doing more harm than good,” Schmidt says. “As long as propoxur is applied by a certified, licensed applicator, the risk is minimal compared with the harm the public is inflicting on themselves with less than productive mitigation methods.”

Indeed, Jones and others say EPA has set the safety bar so high for propoxur and other insecticides that it would be difficult to get approval for any existing chemical, let alone new chemistries. EPA demands such a high safety factor, Jones says, “that nothing is going to pass. It’s extremely harsh.”

CropLife’s Vroom notes that the pest control industry has developed application techniques that effectively contain and limit human exposure, including children’s exposure, to pesticides. “It’s crazy,” he says of the denial to use propoxur against bedbugs. “We’ve got tools that work and can be brought to market.”

“The chances of somebody getting really sick from propoxur are extremely small,” University of Kentucky’s Potter says. “A child would have to be licking the baseboard eight hours a day for the rest of his or her life.”

Tests of propoxur, another carbamate, and an organophosphate “just knocked the socks out of the bedbugs” taken from field populations, Potter says. “They looked very good. It was pretty convincing. Where we’re at with bedbugs, we need every arrow in the quiver.”

But Potter says it is “the politics of pesticides” that binds EPA’s hands. “They will probably be sued from 20 different directions,” he says, should the agency grant Ohio’s request.

Meanwhile, people afflicted with bedbugs increasingly turn to extreme measures to eradicate the pests. Bob Rosenberg, senior vice president of the National Pest Management Association, says members of his association report incidents of people buying powerful agricultural chemicals and then spreading them around living areas or pouring them on mattresses to the point of saturation.

Advertisement

Strickland cited one such incident in his letters to Jackson. A desperate home owner, he wrote, hired an unlicensed exterminator to treat the property for bedbugs. “The applicator sprayed the interior of the duplex to the point of saturation with a product called malathion. The tenants, including one small child, were treated for chemical exposure at a local hospital.”

On its website, EPA lists “products that we don’t want people to use ever,” Miller of Virginia Tech says. An example is pyrethroid-based total-release aerosols—also known as bug bombs. People with infestations will set up 30 bug bombs and leave the oven pilot light on, resulting in explosions and fires, she says. What’s more, bug bombs mostly just cause bedbugs to scatter.

“EPA doesn’t understand the level of pesticide misuse,” Jones says. “People are using lawn care products indoors. They are exposing themselves to more pesticides than need be.”

“They’re just using their own concoctions,” Mallory says of those who cannot afford professional exterminators. He cites cases where people have sprayed rubbing alcohol, which is flammable and has resulted in house fires, to kill the bugs.

The flip side of using hazardous chemicals is using compounds that don’t work at all, Rosenberg says. “The government hasn’t done anything to stop the unscrupulous marketing of such remedies. EPA could take action, but so far they have not.”

For instance, Jones explains, the agency maintains a list—the so-called 25b list—of chemicals “generally regarded as safe.” Many of these compounds are natural products, such as cedar oil, which has been touted as a “natural” solution to bedbug infestations.

“But there’s no efficacy data,” Jones says. “So you have all of this snake oil on the market. People are left to fend for themselves in trying to figure out what works. We have been telling EPA for years that this is a growing problem, but they’re just dragging their feet.”

In the search for solutions, research is critical. Experts note that during the relatively brief window of time when bedbugs nearly disappeared, bedbug research pretty much ground to a halt as well, leaving a huge gap in knowledge.

Miller says EPA currently provides funding to search for effective bedbug pesticides to only one government researcher. “We’re not seeing funding for the things we need to do,” she says.

Among other research needs, entomologists say, is investigation of the possibility that bedbugs are a disease vector. Some evidence suggests that they carry infectious agents on their exoskeletons and spread the pathogens passively, Jones says. She says this potential should prompt more investigation.

Gene studies might shed light on the resistance problem, Jones adds. And sequencing the bedbug genome, Feldlaufer says, might reveal new vulnerabilities of the insects and “bring a different cadre of scientists to the bedbug problem.”

For now, experts say, integrated pest management is the best way to control bedbugs. This approach requires chemicals but also preventive measures such as monitoring and regular inspection, laundering, vacuuming, removing clutter, and sealing up cracks in walls and baseboards, especially in multiunit housing.

“Cleanliness has a lot to do with getting rid of them,” Feldlaufer says.

But the bedbugs are not going away anytime soon, Miller and other entomologists say. The epidemic is still in an explosive phase, she says. “I expect it will get worse before it gets better.”

Although it would be nice to think that the federal government could come in and just solve the problem, “prevention comes on an individual basis,” Miller says. “You need to keep them out of your house.”

One hundred years ago, she continues, “people had bedbug consciousness. We need to get that back. Look at things before coming back in the house—purses, gym bags, computer bags.” When traveling, people should check the mattresses and headboards in hotel rooms and inspect luggage when they return home. Clothes in suitcases should be immediately washed and dried in a dryer.

Bedbugs “are a biological system we were able to live without for about 50 years,” Miller says. Now they are back, and “asking the federal government to step in and stop it is like asking the government to stop the wind.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter