Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

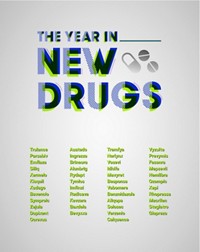

Pharmaceuticals

Behind The Surge

A swell in FDA approvals has many wondering whether the drug industry has finally gotten better at R&D

by Lisa M. Jarvis

August 1, 2011

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 89, Issue 31

Since January, the Food & Drug Administration has approved as many new molecular entities, or NMEs, as it did in all of 2010. The statistic has led drug industry watchers to wonder what prompted the seemingly sudden improvement in productivity and to ask whether companies can sustain this pace of new approvals.

A popular explanation for the surge in new drug approvals, or NDAs, is that big drug companies, after a period of R&D restructuring, have become better at developing drugs. That was the conclusion of a front-page article in the Wall Street Journal last month.

There’s no doubt that big pharma has already had more success this year than in recent history. Of the 21 NMEs approved so far, 13 are owned by major drug companies, compared with just eight in all of 2010. But C&EN’s examination of the products winning approval in the past seven months shows that the jump is not the result of recent shifts in R&D strategy but rather the culmination of years, if not decades, of drug discovery and development work.

John L. LaMattina, former head of R&D at Pfizer, traces the approval spike to technology advances, such as high-throughput screening, that occurred in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Indeed, in nearly every instance, the discovery and lead optimization work on the new drugs began in the mid- to late 1990s. Of the 21 products approved, at least 16 were discovered before 2000, and in one instance, as early as 1993.

Moreover, delving into the provenance of the compounds shows that many were discovered outside big pharma. Of the 21 NMEs, only eight started out in a major drug firm’s labs: Takeda Pharmaceutical’s hypertension drug Edarbi, AstraZeneca’s thyroid cancer drug Vandetanib, Merck & Co.’s hepatitis C treatment Victrelis (developed at Schering-Plough), Novartis’ chronic obstructive pulmonary disease treatment Arcapta, Bayer/Johnson & Johnson’s anticoagulant Xarelto, Bayer’s imaging agent Gadavist, AstraZeneca’s anticoagulant Brilinta, and J&J’s HIV treatment Edurant (developed in collaboration with several organizations).

Several of these compounds might have hit the market earlier were it not for regulatory setbacks or FDA information requests tied to postapproval monitoring. For example, Arcapta, a treatment for serious lung disease, was delayed nearly two years after FDA asked Novartis for more information on the dosing of the drug in 2009.

And both of AstraZeneca’s NMEs had bumpy regulatory trajectories. In December, FDA asked the firm for further analyses on its blood thinner Brilinta, despite a 7-to-1 vote by its advisory committee in favor of approving the drug. The agency had already delayed the committee’s decision by three months, and the additional data gathering meant the drug was approved 10 months later than anticipated.

Meanwhile, FDA delayed by three months its decision on AstraZeneca’s thyroid cancer drug Vandetanib in order to evaluate the postapproval risk evaluation and mitigation strategy submitted by the company. The drug had already experienced major setbacks in its development: In 2009 AstraZeneca withdrew applications in the U.S. and Europe seeking approval for the drug, then called Zactima, to treat lung cancer.

Many of the other approved molecules changed hands over and over again before finally finding a home. Collaboration with biotech firms was also critical for big pharma: Two of the more promising drugs approved—the melanoma treatment Yervoy and the lupus drug Benlysta—were products of big pharma tapping biotech firm expertise in developing monoclonal antibodies.

Despite the caveats, the list does contain some good news about the drug industry’s innovative powers. Of the 21 drugs approved so far this year, at least eight are first-in-class, meaning they are truly innovative, offering more than incremental improvement over existing therapies.

Furthermore, the list includes four drugs for diseases with few good treatment options: Benlysta is the first treatment for lupus erythematosus in half a century; Victrelis and Incivek both represent the first new therapies for hepatitis C in decades. Similarly, Optimer Pharmaceuticals’ Dificid is the first antibiotic in 25 years to combat Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea, a serious infection of the inner lining of the colon.

The second half of the year should bring another spate of innovative drugs, in particular for cancer. For example, Seattle Genetics is likely to gain approval for Adcetris for the treatment of Hodgkin’s leukemia and anaplastic large cell lymphoma.

Last month, an FDA advisory panel unanimously voted in favor of approving the drug, meaning it will likely get the regulatory green light later this year (C&EN, July 25, page 10). Adcetris would be the only marketed antibody-drug conjugate, a class of drug that links a tumor-specific antibody to a powerful chemotherapeutic, delivering the therapy directly to cancer cells and lessening the harsh side effects associated with chemotherapy.

Moreover, many of the cancer compounds on deck for FDA review have enjoyed expedient clinical programs, thanks to breakthroughs in understanding the biology of certain tumors. In May, Roche and Plexxikon filed an NDA for vemurafenib, a treatment for people whose melanoma is being driven by a mutation in the gene encoding the kinase B-Raf; if accepted by FDA, the compound could gain approval by the end of the year. The filing comes just six years after the molecule was discovered—breakneck speed in the world of pharmaceutical development.

Pfizer’s lung cancer treatment crizotinib also enjoyed a quick path to NDA filing. Originally intending to block c-Met, a protein implicated in tumor metastasis, medicinal chemists at Sugen began the discovery work that led to crizotinib just over a decade ago. Sugen was acquired by Pharmacia, which was later bought by Pfizer.

In 2007, Japanese researchers found that some lung cancer patients carried a fusion gene that was behind their disease. Around the same time, Pfizer determined that its molecule also blocked part of the fusion protein encoded by this gene, the kinase ALK. In Phase I trials at the time, the drug has swiftly moved through the clinical paces. Pfizer completed its NDA submission in May, and given the drug’s priority review status, it could be approved by the end of the year.

Incyte’s ruxolitinib similarly enjoyed a fast track: The chemistry campaign that led to discovery of the compound began in 2004; a year later, the JAK2 mutation linked to certain blood cancers was discovered; and in June, Novartis and Incyte filed an NDA for the JAK inhibitor, along with a request for priority review.

The shortened development timelines for cancer therapeutics—not to mention the significant improvement in outcomes for patients receiving the treatments—suggest big pharma is getting better at R&D in areas where fundamental disease biology has been elucidated.

Outside of cancer, big drug firms have other important new drug filings in areas such as arthritis and cardiovascular disease planned for the next three years, suggesting the swift pace of approvals will continue.

The surge in NDAs “is real and is going to last a few years,” says LaMattina, now a senior partner at the life sciences venture capital firm PureTech Ventures. Still, he questions whether the improvement is sustainable. The next four or five years are shaping up to be good ones for big pharma firms, but the past decade’s tumult of mergers and R&D cuts could lead to another slowdown starting in 2018 or so.

“It’s like a tsunami starting way out in the Pacific,” LaMattina says. “It’s hard to tell what kind of an impact it will have.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter