Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Business

Women in Industry

Women show marginal gains in this year’s edition of the C&EN survey of female executives

by Alexander H. Tullo

August 8, 2011

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 89, Issue 32

Year after year, C&EN and other institutions conduct surveys on the representation of women in the upper management of corporations. Year in and year out, the results are basically the same: Women make progress in small increments, but overall the representation of women remains meager.

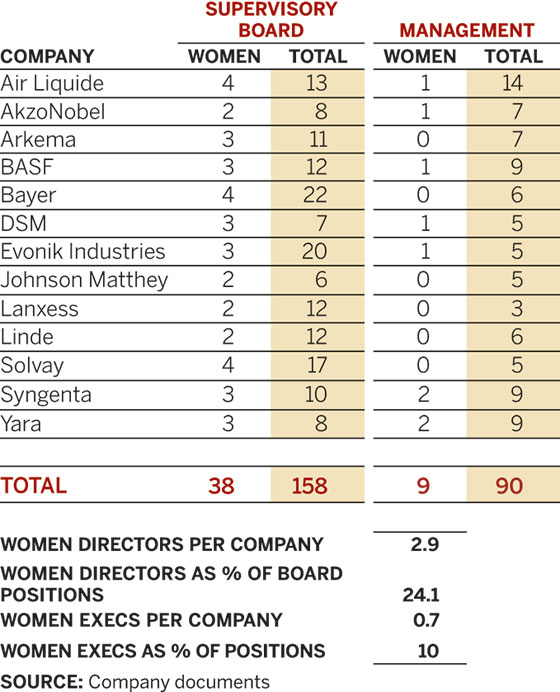

C&EN’s latest survey finds that 52 of the 399 directors at 42 leading U.S. chemical firms are women. That is an average of 1.2 female directors per company and 13.0% of the total number of board positions.

The numbers represent a step backward. C&EN’s survey of the same firms a year ago found that they had an average of 1.3 female directors and a 13.3% representation of women on their boards overall.

Female executives did make some gains. This year’s survey shows 43 female executive officers at chemical firms, out of a total of 413 such officers. The rate of about one female executive officer per chemical company is nearly the same as last year’s. However, the overall representation of women increased from 9.5% a year ago to 10.4% today.

To conduct the survey, C&EN consults company annual reports as well as proxy statements and 10-K filings with the Securities & Exchange Commission from major, publicly traded U.S. companies that have significant chemical businesses.

C&EN attempts to survey the same firms year after year, but mergers and acquisitions make it necessary to occasionally add and subtract firms. This year, Olin is replacing Sterling Chemicals, which is being acquired by Eastman Chemical. For year-over-year comparisons, C&EN’s 2010 survey has been revised to account for the changes.

Although C&EN’s methodology is the best way to compare companies over different years, it doesn’t account for every woman sitting in an important industry position. Stephanie A. Burns, chairman of Dow Corning, doesn’t make the survey because she serves at a joint venture, not a public company. Prominent female executives such as Anne P. Noonan, president of Chemtura’s Great Lakes Solutions unit, sometimes aren’t executive officers of their firms. Women who head private companies and start-up firms also don’t make the list. One is K’Lynne Johnson, chief executive officer of biobased chemicals start-up Elevance Renewable Sciences.

But most women in the highest reaches of the chemical industry do get picked up in the survey. They include Ellen J. Kullman, DuPont’s CEO since the beginning of 2009, and Lynn L. Elsenhans, who has been CEO of Sunoco since 2008.

C&EN’s survey is inspired by surveys of women in upper management and on the corporate boards of Fortune 500 companies conducted by Catalyst, a New York City-based organization that advocates for the advancement of women in business.

The Catalyst survey released in December 2010 found that 15.7% of 5,520 company directors are women, up from 15.2% the year before. It also showed that 14.4% of 5,110 executive officers are women, an increase from 13.5% in its 2009 survey. When the study was released, Catalyst President Ilene H. Lang bemoaned the slow progress. “This is our fifth report where the annual change in female leadership remained flat,” she remarked. “If this trend line represented a patient’s pulse, she’d be dead.”

Companies have been trying to address the paucity of women in their top executive ranks through mentorship programs, advantageous work-life balance policies, and other initiatives. However, the surveys show that such efforts have yet to move the needle very much.

Anecdotal evidence suggests that obstacles to women’s advancement can lurk deep within corporate cultures. In February, while discussing Deutsche Bank’s efforts to put more women on its executive board, CEO Josef Ackermann reportedly quipped that more women would make the board “prettier and more colorful.” The remark sparked strong condemnation.

Sheryl Sandberg, Facebook’s chief operating officer, has emerged as a prominent voice regarding the obstacles women executives still encounter. At the TEDWomen conference in Washington, D.C., in December, Sandberg gave aspiring female executives three main pieces of advice.

“Sit at the table,” she advised. Women, she said, have a tendency to underestimate their abilities compared with men. And they often attribute their success to external factors rather than their own efforts. “No one gets the promotion if they don’t think they deserve their success, or they don’t even understand their own success,” she said.

Even today, Sandberg noted, women do twice the amount of work around the home than men do. “She’s got three jobs or two; he has one,” she said. “Make your partner a real partner,” was her second message.

Sandberg’s third piece of advice was, “Don’t leave before you leave.” This can happen to a woman at the point in her career when she starts making room in her busy life for children. “And literally from that moment, she doesn’t raise her hand anymore, she doesn’t look for a promotion, she doesn’t take on the new project,” Sandberg said. “She starts leaning back.”

Betty Spence, president of the National Association for Female Executives, says she agrees with “99%” of what Sandberg says. “She doesn’t really blame women,” Spence says. “She is just offering them advice.”

But Spence sees a lot more that companies can do to foster female leadership. “The women don’t need to be fixed,” Spence notes. “The women are just fine. The issue is always what the corporate culture is. Does it allow them the opportunity to advance, improve, and excel on a playing field that is level for both men and women?”

On Sandberg’s third point, Spence notes that “there must be an opportunity for women to have their families and have their jobs. Work does not have to be done like it has always been done, the way it was done by men.”

And she says women ought to seek employment at companies that have proven records in female advancement. One example in the chemical industry is DuPont. “Do your homework when you choose your company and find one where you see women at the top and where there is the possibility to succeed,” she says.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter