Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Careers

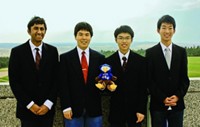

High Expectations, High Achievement

School Aims To Enable Poor Children To Build A Better Future

by A. Maureen Rouhi

October 24, 2011

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 89, Issue 43

Near Tachet Village, outside the city of Siem Reap, 200 miles northwest of Phnom Penh, a college preparatory school seems out of place. With landscaped spaces, sparkling-clean buildings, and smartly uniformed students, the Jay Pritzker Academy is like a spaceship amid rice paddies. It hopes to prove that high expectations in a nurturing learning environment lead to high achievement even among the most underprivileged. It aims to prepare 100% of its graduates for college education in the U.S., and it expects its students to be among Cambodia’s future leaders.

The academy is modeled after Providence St. Mel, a school on the West Side of Chicago that has consistently sent 100% of its graduates to four-year colleges. The curriculum is based on high expectations and high accountability on the part of both students and teachers and learning that cultivates critical thinking and subject mastery.

The academy’s past and current students—326 students so far—from prekindergarten to grade 11, receive three free meals per day, eight free uniforms per year, free schoolbooks and materials, and a free hygiene kit containing toothpaste, a toothbrush, shampoo, and soap (plus deodorant for those in grade five and above) per month. In return, students come to school well-groomed, proud in their blue-and-white uniforms, and committed to work to the best of their abilities.

The school day begins at 7:40 AM, but by 6:45 AM, about 250 kids are already waiting at the campus gates. “They want to be here,” says Steven McCambridge, the school’s director of facilities, about the students, who come from impoverished families in the surrounding villages. “If we told them they could get in at 6:30 AM, they’d be here even earlier,” adds Hedi Belkaoui, the school’s principal. The school day concludes at 3:30 PM, but many students stay until 5 PM to meet with teachers or to use computers, McCambridge says. And students regularly bring home two to three hours’ worth of homework.

Instruction is in English and Khmer; the average class size is 25 students; the female:male ratio is 3:2. Classrooms have modern amenities—computers with high-definition liquid-crystal-display monitors for instruction, microscopes, and emergency showers in the science rooms. School buses transport the children who live far, and a clinic provides basic medical care.

In class, students are attentive and well behaved. Their desire to learn is palpable. “We have to work hard,” a high school student replies when McCambridge asks why he is in school. “When we grow up, we want to build our future to have a bright life so we can live easily.”

Whether the academy will achieve its goal of 100% acceptance to U.S. universities remains to be seen. Its first batch of students are still in grade 11.

Given Cambodia’s poverty and backwardness, is it possible that the academy may be setting up these children for unrealistically high expectations about how their lives will turn out? “I’ve heard this question a lot,” Belkaoui says. “What we’re doing now is good. It’s not my role to decide what Cambodia will do for this new class of people that comes back being highly educated.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter