Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Environment

Safety Rules For Sewage Sludge May Be Outdated

Biosolids: Noroviruses survive treatments that kill Salmonella and other pathogens

by Emily Gertz

June 15, 2011

People have used human waste for thousands of years to fertilize cropland and gardens. In comparison, federal regulations for using such “biosolids” on land are young: They have been in effect for about 30 years. Nonetheless, they are out of date and may put public safety at risk, according to researchers. Their study finds that biosolids that meet federal standards may still spread emerging pathogens such as noroviruses, a family of microbes that causes stomach flu (Environ. Sci. Technol., DOI: 10.1021/es200566f).

Waste processors have several options for treating biosolids to remove pathogens or reduce their levels, including heat treatment, composting, and irradiation. In 1993, the Environmental Protection Agency updated its regulations by establishing standards for pathogen levels in biosolids destined for land applications, including fertilizing crops. One goal of these regulations was to lower the risk of infection for people living or working in areas near treated lands. In those areas, people may breathe in Salmonella, enteroviruses, and other pathogens contained in the dust blown off biosolid-treated lands.

The regulations have worked well on Salmonella and enteroviruses, says Jordan Peccia, an associate professor of chemical and environmental engineering at Yale University. To find out whether they also protect against emerging pathogens, he and his colleagues compiled data from previous studies that had measured the pathogen content in biosolids deemed safe for land application, and did new risk analyses.

First the researchers reanalyzed the risks of infection from well-known microbes. They found that people who inhale dust 30 meters away from land treated with sewage sludge would have a median yearly probability of infection by enteroviruses of around 1 in 1,000,000. Enteroviruses can cause illnesses ranging from common colds to meningitis.

But when their analyses included noroviruses, the yearly risk for infection via inhalation rose dramatically, to at least 1 in 1,000. Noroviruses cause more than half of all foodborne gastroenteritis outbreaks in the U.S., according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

This result, says Peccia, shows that the biosolids treatments that eliminate enteroviruses or Salmonella, or reduce them to levels the government deems acceptable, can leave behind potentially harmful levels of emerging pathogens. Unfortunately, very few epidemiological studies have looked at ties between infections and biosolids, Peccia says. As a result, he and his colleagues don’t make firm recommendations on how to lower the risks. Still, Peccia says that a logical response from EPA would be to mandate that sewage sludge processors use the best available treatments, which heat sludge to effectively pasteurize it, and reduce the levels of pathogens like norovirus, he says.

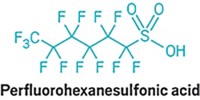

This study demonstrates that testing for pathogens is “behind the times,” says Michael Hansen, senior scientist with the nonprofit Consumers Union. EPA’s ignoring emerging pathogens could result in underestimating risk by orders of magnitude, he says. However, Hansen worries even more about sewage sludge’s potential for harboring toxic industrial chemicals like flame retardants, as well as pharmaceuticals excreted from the body, such as birth control drugs and antibiotics. These substances may cause illness if they are absorbed by crops and enter the food supply, he says, but none are being tested for or removed from sludge.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter