Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Physical Chemistry

Curiosity On Mars

by Rudy M. Baum

September 3, 2012

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 90, Issue 36

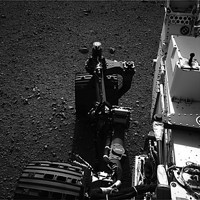

The images are almost mundane. Black-and-white pictures of a barren landscape, a mountain in the distance, tire tracks in the dust leading nowhere.

And then you realize that the pictures were taken by a machine named Curiosity sitting on a planet more than 150 million miles away from Earth. A machine designed and built by humans, launched into space in November 2011, and landed on Mars on Aug. 6 using a complex series of maneuvers never before tested. A machine that will travel across miles of martian terrain and climb a mountain searching for traces of past (or present) life.

Unbelievable. My two sons, Rudy Jr. and Greg, are 25 and 23 years old, and they have never known a world that did not include satellite images of weather systems, real-time television broadcasts from anywhere on Earth, and an almost continuous human presence in space.

By contrast, I was four years old when Sputnik 1 was launched. I have a clear memory of standing outside my Uncle Oscar’s house in Collingswood, N.J., on a chilly autumn evening with my mom and dad and aunt and uncle scanning a clear sky for a moving trace of something I didn’t understand and never saw. I remember watching broadcasts of a number of U.S. rockets blowing up during or shortly after launch. I remember watching a black-and-white TV in a third-grade classroom in Mount Laurel, N.J., in February 1962 when John Glenn became the first American to orbit Earth.

I was 15 years old when the Apollo 11 mission landed on the moon. Like the current landing of Curiosity on Mars, the moon landing also involved machines that had never fully been tested because they couldn’t be. I had really never before thought about the courage of Neil Armstrong (who passed away at the age of 82 on Aug. 25) and Buzz Aldrin when they descended in the LEM to land on the surface of the moon. There was a very real chance that they’d crash during the landing or never make it off.

Nowadays, we take space for granted. When my wife, Jan, and I are on vacation in a place where there are few lights and the night sky is truly dark, we often sit outside shortly after sunset and look for satellites streaking across the dome of the sky. We always spot two or three or four in a matter of a half hour or so.

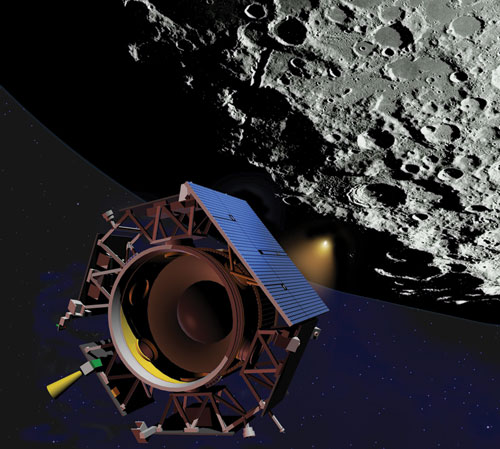

There are three satellites currently orbiting Mars. In fact, humans have sent probes to all of the planets in the solar system. In addition to the missions currently active on Mars, spacecraft are continuing to probe Earth’s moon, Saturn and its rings and moons, Mercury, and asteroids and comets. Voyager 1, launched 35 years ago to explore Jupiter and Saturn, is now 11 billion miles from the sun and on the verge of leaving the solar system and entering interstellar space.

There is grandeur in these missions of human exploration and discovery. They elevate humanity, and they must continue.

Thanks for reading.

Views expressed on this page are those of the author and not necessarily those of ACS.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter