Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Pharmaceuticals

For Migraine Prevention, An Antibody Strategy

Injectable therapies could realize a drug target’s promise

by Carmen Drahl

November 19, 2012

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 90, Issue 47

Following migraine drug discovery efforts can be an emotional roller coaster for chemists and migraine patients. Both groups have been buffeted by the promise of calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP), a neuropeptide implicated in migraine development, as a new drug target. And both have been disappointed because that promise has yet to translate to new migraine drugs.

Two firms are now evaluating drug candidates they say could fulfill CGRP’s potential. These new candidates are antibodies rather than the small molecules that are the typical denizens of the migraine drug pipeline.

For example, Alder Biopharmaceuticals, a Bothell, Wash.-based company, is studying ALD403, a monoclonal antibody, in a Phase I clinical trial in healthy volunteers. And Arteaus Therapeutics, a two-person firm in Cambridge, Mass., was founded for the purpose of developing LY2951742, an antibody licensed from Eli Lilly & Co. That antibody is now in a Phase II clinical trial in patients with migraines.

Migraines are debilitating headaches characterized by pain accompanied by nausea, sensitivity to light, and visual disturbances called auras. The gold-standard migraine therapies are the triptans, small molecules that stimulate specific serotonin receptors to constrict blood vessels in the brain and alleviate symptoms. However, about half of migraineurs, as sufferers are called, don’t respond to the drugs or cannot take them because of their cardiovascular risks. Even when triptans are effective, they don’t prevent migraine attacks.

“The development of CGRP antibodies is all about migraine prevention,” says Peter J. Goadsby at the University of California, San Francisco, who in the 1980s co-led a team that learned that neurons release CGRP during migraines. A handful of drugs are approved for migraine prevention, but they aren’t widely used.

“In migraine management, you want to hit hard, and you want to hit early,” says Alder’s chief scientific officer, John A. Latham.

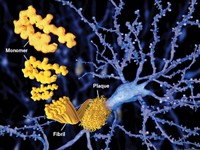

Drugs targeting CGRP would work differently from triptan medications. Neurons release CGRP during migraines; the peptide has a role in transmitting pain and factors into the propagation of other symptoms as well. Clinical trials from other companies have shown that blocking CGRP treats existing migraines without the triptans’ cardiovascular side effects.

Both firms’ CGRP antibodies are designed to latch onto the CGRP peptide so it cannot interact with its receptor. This is in contrast to small-molecule CGRP drug candidates, which bind to the receptor to prevent CGRP action. Ideally, says Latham, antibodies could be administered at the start of each month. They would not be metabolized as rapidly as small-molecule drugs, remaining in the bloodstream to nip nascent migraines in the bud.

One drawback to these antibody drugs is that even at once-per-month dosing, they would be more expensive than most small-molecule drugs would be. However, Alder’s chief business officer, Mark J. Litton, says his firm’s yeast-based antibody-making platform is more cost-efficient than bacterial or mammalian-cell antibody-making methods. The goal, Litton says, would be to set the antibody’s price at about $5,000 to $8,000 a year. That range, he says, is comparable to the cost of Botox injections. Botox can also be used for migraine prevention, although its mechanism for that use is unclear.

Alder and Arteaus are banking on the idea that the side effect profile of CGRP antibodies will prove better than those of some small-molecule migraine drugs. In its 2009 annual report, Merck & Co. disclosed that a small number of patients taking its investigational small-molecule CGRP receptor inhibitor telcagepant twice daily for migraine prevention had elevated liver transaminase enzymes, an indicator of liver damage. The company halted development of telcagepant in 2011 in light of “an assessment of data across the clinical program,” according to a financial statement. Another inhibitor, MK-3207, was pulled because of liver test abnormalities. Both Alder and Arteaus officials say they believe the liver effects are specific to the withdrawn compounds and are not likely to be side effects of CGRP antibodies.

Not all specialists consider prevention to be a critical property of migraine medications. To Lars Edvinsson of Sweden’s Lund University Hospital, the other leader of the 1980s team that made fundamental CGRP discoveries, prevention is necessary only in cases of long-lasting migraine attacks or in patients with more than three attacks per month. He thinks most migraineurs don’t fall into those categories. “As a doctor, I prefer to treat the attack, and when the attack is over there is no need for further medication.”

Others believe prevention is a major advantage. In a large survey by migraine experts of headache sufferers published in 2007, 31.3% of migraineurs reported having three or more migraines a month. Symptoms varied in intensity, with 53.7% of migraineurs reporting severe impairment and the need for bed rest during an attack (Neurology, DOI: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000252808.97649.21). The study was funded in part by Ortho-McNeil Neurologics, a company that makes the antiseizure drug topiramate, which is also used for migraine prevention. The study team concluded that 38.8% of migraineurs should be considered for preventive therapy, but only 13.1% receive it. That “seems more than a passing few” who need prevention, if one takes the study at face value, Goadsby says.

More fascinating than the question of prevention, Edvinsson thinks, is the question of where CGRP antibodies act. The CGRP peptide and its receptor reside in both the brain and the peripheral nervous system. His team found that CGRP antibodies cannot traverse the blood-brain barrier (Br. J. Pharmacol., DOI: 10.1038/bjp.2008.346). So if the antibodies work to treat migraine, it could mean they’re acting outside the brain. That seems crazy for a headache disorder, he says, but if true it could prove to be a big leap in scientists’ understanding of migraine.

That site-of-action knowledge will be useful to ongoing drug development efforts. Both antibodies and small molecules are making their way through clinical trials. Though time will tell whether any drugs will be approved, says Arteaus Chief Executive Officer David S. Grayzel, “I wouldn’t be running this company if I didn’t believe in CGRP.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter