Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Policy

Patent Tectonics

The new U.S. system for patent filing is the most significant change under the America Invents Act

by Glenn Hess

March 11, 2013

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 91, Issue 10

The first major overhaul of U.S. patent law in six decades is about to fully kick in. Although the changes will bring the U.S. patent system more in line with patent offices around the world, they constitute a break with the past for many domestic inventors.

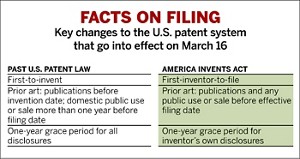

Beginning on March 16, the U.S. will abandon its very complicated and often time-consuming system for determining who gets the patent when two people claim to have invented the same technology. In addition, the information used to determine whether an invention is patentable will be expanded and the yearlong grace period inventors have had to file a patent application will be redefined.

Instead of trying to establish who came up with the idea first—the long-standing first-to-invent rule of priority—the U.S. Patent & Trademark Office (PTO) will now award the patent to the first inventor who files an application on the technology.

The switch to a first-inventor-to-file standard is a hallmark of the Leahy-Smith America Invents Act (AIA ), the historic patent reform legislation that, after years of debate, Congress passed and President Barack Obama signed into law in 2011.

AIA is intended to hasten the pace of innovation by simplifying and streamlining the complex U.S. patent system, which has invited increased litigation in recent years. “Migration to a first-inventor-to-file system will bring greater transparency, objectivity, predictability, and simplicity to patentability determinations,” says Acting PTO Director Teresa Stanek Rea.

The word “inventor” is significant: AIA includes safeguards to ensure that only an original inventor or his or her assignee may be awarded a patent, she points out.

Moving to a first-inventor-to-file system is also “another step towards harmonizing U.S. patent law with that of other industrialized countries,” Rea notes.

U.S. patent law has operated under the first-to-invent standard since the first patent statute was passed by Congress in 1790, about two years after the U.S. Constitution was ratified. This system awards patent rights to the individual who can prove he or she was the first to create an invention.

Other industrialized countries have long used the first-to-file system, which awards patent rights to the first person to file an application for the invention, regardless of the date of invention.

“It is a sea change if the initial filing is only in the U.S.,” says Kendrew H. Colton, a partner in the Washington, D.C., office of Fitch, Even, Tabin & Flannery, an intellectual property (IP) law firm. “In that sense, it may go down as having as big an impact as the Patent Act of 1952,” he says, referring to the last time Congress made significant changes to U.S. patent law. That act required that an invention be new and useful, as well as nonobvious, to be granted a patent. In addition, the statute established penalties for infringement.

But for those who file patent applications internationally, the change will be less dramatic, points out Colton. “It’s not a situation where the ‘sky is falling.’ ”

Nevertheless, many attorneys believe other changes made under AIA will soon make securing and enforcing a patent in the U.S. more difficult. “This will have significant implications for the branded pharmaceutical and chemical industries because they essentially live or die based on their patents,” says George F. Wheeler, a patent lawyer at Chicago-based IP law firm McAndrews, Held & Malloy.

One reason is that the scope of what constitutes prior art, a key factor in determining patentability, will expand under AIA. Currently, prior art in the U.S. patent system includes all publicly available publications and any information on domestic use or sale of the invention before the invention was made. An invention isn’t eligible for a patent if it has been described in or is obvious from prior art.

Under the new law, information on public use or sale of the invention outside the U.S. will become prior art as well. The expanded definition applies to any information publicly available prior to the patent filing.

“More items are now available to the patent office to reject an application,” says Matthew P. Becker, an attorney in the Chicago office of IP law firm Banner & Witcoff. “For example, a patent applicant may have a claim rejected under the new statute based on something that would not qualify as prior art under the old statute.”

The new system also limits the one-year grace period that currently protects an inventor from prior art, says Otis Littlefield, a partner in Morrison & Foerster’s San Francisco office. Under first-to-invent, an inventor could wait for years before filing a patent application. The grace period allows the inventor to still obtain a patent even though someone else published, publicly used, or sold the invention up to one year before the inventor filed the patent application.

In contrast, Littlefield explains, the new one-year grace period protects the inventor against disclosures made by the inventor or obtained from the inventor. “This could happen, for example, if collaborators publish a paper that includes the invention that they obtained from the inventor,” he remarks. “On the other hand, if a competing lab independently develops the same invention and publishes it, that publication can bar the inventor from obtaining a patent.”

The law’s complexity makes filing a patent application after a public disclosure extremely risky, says Katharine Ku, director of Stanford University’s Office of Technology Licensing. It will be important for inventors to disclose information about their discoveries to the technology licensing office prior to publication, giving the staff enough time to evaluate the invention, she says.

An inventor first files an application for patent with PTO; this starts the official record of a patent. Once a complete application is filed, it is scheduled for examination. The inventor’s application must include an enabling written description (disclosure) of the claimed invention, and PTO examiners then determine if a patent is warranted.

A good time for inventors to submit their discoveries to the technology licensing office for review “is when there is enough data to support the filing of a patent application, often when a manuscript is being prepared,” Ku remarks. Her office will still evaluate each invention for commercial potential when it is submitted. But “we will not even consider filing a patent application if the invention has been publicly disclosed.”

Ku says her office believes it makes more sense strategically to proceed as if the U.S. had transitioned to a true first-to-file system, as exists in Europe and Japan. There, no grace period exists; if an inventor makes a public disclosure before filing a patent application, the invention is not patentable.

“Under the new law, it’s a race to the patent office, and once you’ve published, all bets are off,” she remarks. “We want researchers at Stanford to come to us so that we can decide whether or not to file a patent application before they publish—period.”

Patent lawyers say the AIA reforms may favor big corporations over the smaller innovator. “Global companies that seek patent protection around the world have operated in first-to-file systems for years. So many companies already have a race to the patent office mind-set,” Becker notes.

Colton says the new system for patent filing in the U.S. is “likely to affect start-ups, solo inventors, and universities, among others, who may lack the deep pockets to finance many rush-to-the-patent-office-type projects.”

Inventors at universities, he adds, are usually in a tug-of-war anyway between filing first versus publishing in scientific literature first. “The first-inventor-to-file aspect of the new law will force earlier ‘patenting’ decisions while potentially impacting budgets of the parties who are caught with their guard down,” Colton says.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter