Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Biological Chemistry

How Mole Rats Defeat Malignancy

Critter Chemistry: Long-lasting, extended hyaluronan polymers in their skin protect naked mole rats

by Sarah Everts

June 24, 2013

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 91, Issue 25

\

\

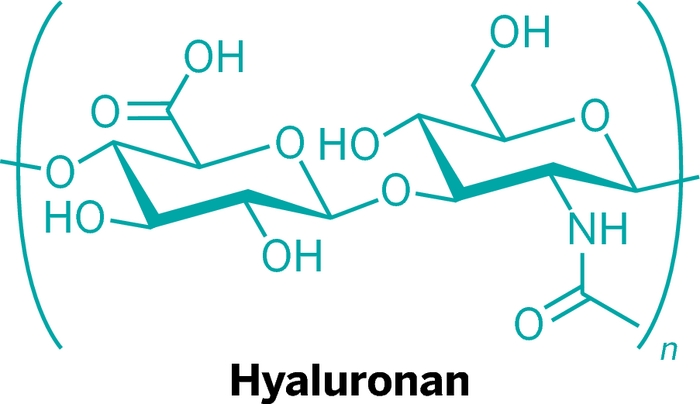

Accumulations of long hyaluronans (shown) enable naked mole rats to live long without cancer.

The naked mole rat is arguably the ugliest mammal in existence, but nature has been kind to it in other ways: Members of the species are extremely resistant to cancer and outlive other similar-sized rodents by decades. The rats can live 30 years, 10 times as long as mice of the same size.

Now researchers led by the University of Rochester’s Vera Gorbunova have figured out at least one part of the naked mole rat’s elixir for cancer avoidance, which may inform anticancer strategies for humans (Nature 2013, DOI: 10.1038/nature12234).

To squeeze through its underground tunnel habitat, the mole rat has extremely stretchy skin. The skin cells, Gorbunova and coworkers learned, produce long hyaluronan polymers that likely confer elasticity. Hyaluronans are polysaccharides found in many tissues, such as the skin and brain. The polymers produced by naked mole rats have extremely high molecular weights—five times larger than that of human or mice hyaluronan.

Mole rats seem to use the long hyaluronan “to provide cancer resistance and longevity,” Gorbunova and her colleagues explain. They found that the polymers interfere with the transformation of normal cells into cancerous ones. When they used molecular techniques to block production of long hyaluronan polymers, or when they boosted degradation of the polymer, the naked mole rat cells could develop cancer.

The long polymer accumulates because the hyaluronan-degrading enzymes of mole rats have low activities, the researchers found. Bryan P. Toole, a cancer researcher at the Medical University of South Carolina, says many in the field had begun to suspect that long polymers of hyaluronan interfere with cancer formation, while short polymers enhance it. This work begins to clarify hyaluronan’s complicated role in cancer and may one day inspire anticancer therapies, he says.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter