Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Environment

Balancing Aquatic Ps And Ns

Pollutants: Less phosphorus means more nitrogen—and algae

by Stephen K. Ritter

October 14, 2013

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 91, Issue 41

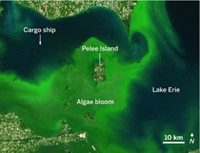

Increasing numbers of ponds, lakes, and rivers around the world are becoming choked with green, slimy blobs of algae, which is having an economic impact on commercial fishing and recreation. This process, called eutrophication, is an unhappy sign of too much phosphorus and nitrogen from agricultural and suburban runoff.

A research study now shows the two nutrients can’t be considered separately when it comes to algae reduction. Trying to reduce phosphorus pollution to curtail algae growth inadvertently leads to an unwanted increase in nitrogen levels elsewhere—and more algae.

The researchers aren’t suggesting easing up on phosphorus controls. They instead argue for increased attention to control of nitrogen sources along with further reductions in phosphorus sources.

“This interesting study has clear implications for understanding the ways lakes respond to efforts to control eutrophication,” says David Sedlak, codirector of the Berkeley Water Center at the University of California, Berkeley, who was not involved in the research. “Previous studies have suggested that nitrogen and phosphorus cycles are interrelated, but regulators often ignore these interactions and focus on one nutrient at a time.”

Ecologists Jacques C. Finlay, Gaston E. Small, and Robert W. Sterner of the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities, uncovered the new phosphorus-nitrogen connection by evaluating long-term phosphorus and nitrogen records in 12 large lakes in the U.S. and Europe (Science 2013, DOI: 10.1126/science.1242575).

In a model the team developed, phosphorus stimulates nitrate uptake by the algae. When there’s less phosphorus, which is the limiting reagent in algal growth, more nitrate stays in the water and migrates downstream, where it can contribute to eutrophication elsewhere, extending the pollution problem.

“These considerations explain why good-faith efforts to manage phosphorus appear to be leading to lakes that are clearer and better oxygenated but more polluted with nitrogen,” writes Duke University biologist Emily S. Bernhardt, in a commentary accompanying the research paper. Bernhardt adds that the results suggest predicting the effects of new regulations requires greater consideration of the links between pollutants.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter