Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Environment

Nuclear Pool Problems

by Josh Fischman

October 28, 2013

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 91, Issue 43

To celebrate C&EN’s 90th anniversary, one Editor’s Page each month examines materials from C&EN Archives. Featured articles are freely downloadable for one month.

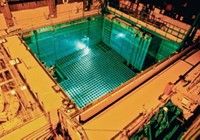

Sometime next month, the electric company running the Fukushima nuclear power facility in Japan plans to start pulling spent fuel rods from a pool inside a reactor building that was heavily damaged in the 2011 earthquake and tsunami. The rods will be relocated to another, safer, pool to reduce the risk of radioactive material leaking into the groundwater around the plant. Water and soil in the area have already been contaminated through a series of spills and malfunctioning cleanup equipment, and rains last week caused radiation levels to spike in a ditch near the plant at 140,000 becquerels per L. That’s 14,000 times as much as the safe limit for drinking water set by Japan’s health ministry, according to a report by Bloomberg News.

But moving the rods is just a temporary fix for a longer-lasting and bigger problem: how to safely store nuclear waste. It is a problem the U.S. must also grapple with, given that there is 70,000 metric tons of high-level radioactive waste currently in this country, and most of it is stored at or near the power facilities that generated it. Much of it is in pools like those used in Fukushima. The U.S., like the rest of the world, has been failing to come up with a better storage solution for decades.

Early on, scientists and policymakers were optimistic, particularly about underground burial. On July 30, 1979, C&EN reported on a Department of Energy study that recommended a multibarrier approach for buried waste. “Such barriers include the waste form, overpack, backfill materials, or any other barriers added to prevent migration of radionuclides to the biosphere,” the magazine said. In a Feb. 10, 1986, article, C&EN noted that the American Institute of Chemical Engineers had concluded that “long and extensive research, development, and demonstration activities in the U.S. and abroad have made possible the safe, permanent disposal of high-level commercial nuclear waste.”

But three years later, the outlook was not as rosy. In a Nov. 13, 1989, article about a congressional panel charged with evaluating underground repositories, such as Yucca Mountain in Nevada, C&EN wrote, “the panel’s report, by all accounts, resolves nothing and is arousing attacks from every side.”

It seems that the public did not believe in the technology. The technical problems for storing nuclear waste seemed solvable, C&EN said in a special report on July 18, 1983. But “to many people, radioactive waste is the most frightening of all toxic by-products of modern industrial society,” it continued, because it carries the long-term specter of cancer and genetic mutations.

But there is also a risk from ongoing storage at nuclear power plants, as Fukushima shows. The World Health Organization, in a 2013 report, estimated a very slight increase in cancers stemming from the accident. For thyroid cancer, the baseline lifetime risk for females is 0.75%. A female infant from the most affected area of Fukushima has an added 0.5% risk.

But you wouldn’t want to be in that fraction if you could avoid it. So thousands have left Fukushima, and Yucca Mountain never opened in the face of public opposition. A thyroid cancer specialist in Japan, now mayor of a small town, has opened a facility to take in Fukushima’s children. “If my fears turn out to be unfounded, nothing would be better news,” he recently told the Associated Press. “But if they become reality, then there is little time before it is too late.”

Next month, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission will examine whether spent fuel in the U.S. should be moved more quickly from pools into dry casks. The debate will be over risk and economics, according to my colleague Jeff Johnson, who follows this issue for C&EN. It would be good if NRC could figure out a way to integrate public perception with technological reality and come to a conclusion other than to do nothing. There are risks in those plant pools and risks in dry storage. A clear explanation of the two would allow people to choose the lesser risk, whichever one it may be.

Views expressed on this page are those of the author and not necessarily those of ACS.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter