Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Business

New Ways To Grow

It’s not about simple expansion anymore, as chemical companies focus on moving deeper into specialties

by Marc S. Reisch

November 11, 2013

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 91, Issue 45

October was a big housecleaning month at some of the world’s major chemical firms. DuPont decided to leave the performance chemicals business by carving it out and giving it to shareholders. Dow Chemical signed a deal to sell its polypropylene catalysts business to W.R. Grace and said it wanted to divest commodity chemicals businesses worth up to $4 billion.

Clariant, meanwhile, completed the sale of its textile chemicals unit to private equity firm SK Capital Partners for $550 million. The firm also outlined deals to sell its detergents and intermediates operations to International Chemical Investors Group and its leather services business to Dutch competitor Stahl.

For all three firms, the divestments were preceded by sizable acquisitions of companies in fields they had identified as more exciting and profitable than their own old low-growth or cyclical businesses.

For DuPont, it was the $6.3 billion purchase of Danisco in 2011, which reinforced the firm’s position in the industrial biotechnology arena. For Dow, the $19 billion acquisition of Rohm and Haas in 2009 made the largely commodity chemical producer a specialty chemical powerhouse. And for Clariant, the 2011 purchase of Süd-Chemie for $2.6 billion helped sharpen the focus on fast-growing specialties.

These strategic sales and acquisitions signal a big change in the chemical industry. In the years leading up to the recession that began in 2008, many chemical companies were content to grow by expanding existing operations into emerging regions of the globe, points out Christopher D. Cerimele, managing director at the investment banking firm Grace Matthews. But many emerging markets that not long ago experienced double-digit growth rates, such as China, are now growing only in the mid to high single-digit range. U.S. and European growth rates are in the low single digits.

Executives, including at FMC and Eastman Chemical, realize they need to do more. Many firms want to exit mature product lines and invest in segments of the market that are growing faster than the overall economy, Cerimele says. And they are looking for areas in which they can develop a competitive edge through research. The quickest way to reshape portfolios to do this is through mergers and acquisitions.

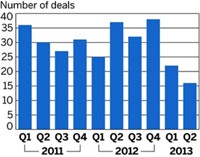

“Focusing on portfolio strategy is a theme now for many chemical firms,” says Kurt Eichhorn, North America chemical strategy head for consulting firm Accenture. They “constantly analyze their portfolios and exit those businesses that don’t meet targets for profitability and growth.” For that reason, he expects a pickup in merger and acquisition activity during the balance of 2013 and into 2014.

But executives also know that buying your way to higher profits doesn’t always work. Clariant, for example, failed with the $1.8 billion acquisition in 2000 of British fine chemicals producer BTP. It ended up shutting some of BTP down and selling the rest for a song in 2007. So this portfolio strategy calls for careful, constant review.

Active portfolio management is behind DuPont’s latest move. “We do a portfolio analysis of our operations at least once, if not twice, a year,” Ellen J. Kullman, DuPont’s chief executive officer, tells C&EN. “We actively manage our portfolio with a focus on higher growth businesses.” Those that don’t fit any longer, such as the automotive coatings business sold to private equity firm Carlyle Group for $4.9 billion, are pushed out the door.

DuPont, Kullman explains, boasts research strengths “in biology, in chemistry, and in materials.” So when analyzing what businesses make sense in the firm’s portfolio, she says the key question is: “How can science make the difference?” For the performance chemicals business, apparently, the answer was: It can’t.

ASSET SHUFFLE

Major players toss out commodities in favor of specialties.

With deep roots in the company reaching back to the 1930s, the performance chemicals business includes titanium dioxide pigments for paint, Teflon nonstick coatings, and refrigerants. Last year they brought in sales of $7.2 billion and operating earnings of $1.8 billion.

These days, most of DuPont’s performance chemicals are cyclical, and that is particularly true for titanium dioxide, which typically cycles through periods of high demand and strong profits followed by times of sinking prices and poor earnings. Because the firm sees little potential for new growth in these businesses, it devoted only $100 million to their research and development in 2012.

On the other hand, DuPont put more than $1.4 billion into researching and developing its agricultural, industrial biotechnology, and performance materials businesses. These businesses had $35.2 billion in sales last year and operating earnings of $6.3 billion.

Last year was the first full year that DuPont’s results included Danisco, the Danish industrial enzymes maker that it bought in 2011. Like the Pioneer Hi-Bred seed business that DuPont bought in 1999 for $7.7 billion, Danisco was a game changer for DuPont.

Just as Pioneer made DuPont a leader in agricultural biotechnology, Danisco made it a force to be reckoned with in industrial biotech. Kullman told the Harvard Business Review in 2012 that DuPont undertook the Danisco acquisition because “we knew this acquisition would enhance our biosciences capability and accelerate the company’s readiness for its next 100 years of growth.”

In the chemical industry, Kullman is rivaled as an aggressive portfolio manager perhaps only by Andrew N. Liveris, Dow’s CEO. And Liveris reminded investors when Dow reported earnings late last month that managing the firm’s portfolio to provide a good return on investments is a priority. Over the past few years, Dow has sold $8 billion worth of businesses, including its styrenics business to private equity firm Bain Capital in 2010 and its polypropylene business to Brazilian chemical maker Braskem in 2011.

Given “slow, hesitant” global economic growth, Liveris said, the firm will continue “deemphasizing our participation in commoditizing nonstrategic markets.” Instead, Dow plans to “go deeper into attractive end-use markets.”

A core pillar of Dow’s growth agenda is its advanced materials business, according to Howard Ungerleider, the business’s executive vice president. Advanced materials include coatings, building solutions, and electronic and functional materials—all acquired with the purchase of Rohm and Haas in 2009.

“Simply put, we are moving away from being all things to all markets,” Ungerleider says. “We are going deeper and narrower into key end-use markets where we can apply our strong science and technology base and highly competitive cost positions.”

Examples of the kind of products Dow is emphasizing, he says, include Evoque polymers, which allow paint formulators to use up to 20% less titanium dioxide, and Polyox water-soluble resins, added to Unilever’s Lifebuoy brand soap to reduce processing costs. They also include Filmtec Eco reverse-osmosis water purification elements, which use 30% less energy than competing filters.

A new technology center, dedicated to Dow’s advanced materials unit, opened in July near Philadelphia with room to house 800 employees. “In 2012, we contributed 20% to Dow’s $57 billion in sales and generated 40% of new patents,” Ungerleider says of the advanced materials business. The technology center “will be the point of discovery for many new innovations to come.”

Whereas Dow’s transformation is still ongoing, Clariant says it has just about completed the heavy lifting in its reorganization. The company was saddled with too many businesses whose products had become commoditized, according to Patrick Jany, chief financial officer.

“Over time, areas that were profitable specialties are subject to increased competition,” Jany explains. “Opportunities to innovate are limited, which ultimately leads to restricted growth and profitability, and so you need to find something else.”

Clariant began to restructure in 2008 at the start of the global economic recession, Jany recounts. The first order of business, he says, was to improve profitability “to get a first-in-class cost position.” Between 2008 and 2011, Clariant cut 20% of its workforce and shut down 20 production sites.

Then in 2011, Clariant paid $2.6 billion for Germany’s Süd-Chemie, a specialty chemical maker that took Clariant into new areas such as catalysts, battery materials, water treatment, and industrial enzymes. After that, Clariant started unloading less desirable assets. “The additional size allowed us to tackle the divestment of historically important areas like textiles, paper, and the leather business,” Jany says.

Now almost complete, the divestment process “leaves us with the portfolio we want to have,” he says. “It will allow us to achieve our targets in the next few years.” The firm aims to achieve operating profit margins of more than 17% by 2015. Excluding discontinued operations, profit margins were 14% in the firm’s most recent quarter.

Privately owned firms may be satisfied with a steady profit every year, Jany says. But as a public company, “we need innovation to deliver new molecules, which then generate incremental value every year,” he notes.

Clariant’s strategy includes healthy contributions to R&D. In 2012, it invested close to 3% of sales in R&D, or about $220 million. Late last month the firm opened a $136 million global hub for research in Frankfurt, Germany. The 36,000-m2 center will house 500 R&D and support staff.

Although perhaps not as sweeping as those at DuPont, Dow, and Clariant, portfolio changes are happening at FMC under the leadership of CEO Pierre R. Brondeau, who helped shape Rohm and Haas’s advanced materials business while with that firm. One change now under way is intended to make the firm, long a supplier of crop protection chemicals, a player in biological controls.

FMC missed the boat in the seed and genetic traits business where Monsanto, DuPont, Syngenta, Bayer, and Dow reign, acknowledges Andrew D. Sandifer, the firm’s vice president of strategic development. But the firm still sees an opportunity to become a leader in other biological techniques for protecting crops and helping them grow.

Last month, FMC signed a deal to acquire the Center for Agricultural & Environmental Biosolutions (CAEB), a lab belonging to contract research organization RTI International. At the same time, FMC also signed a partnership with Chr. Hansen, a Danish cultures and enzymes specialist. The plan, Sandifer says, is to put FMC in the biological controls game by having the Danish firm provide scale-up of microorganisms from CAEB’s extensive library. FMC will provide regulatory, marketing, and distribution services.

FMC is also building its health and nutrition business, purchasing Epax, a maker of omega-3 fatty acids, and South Pole Biogroup, a natural colors and health ingredients provider. These acquisitions all figure into FMC’s Vision 2015, which sets an earnings target for the firm of $1.2 billion by 2015, up from $719 million in 2012.

The firm updated the plan at the end of April to include the divestment of its peroxygen business. The unit makes hydrogen peroxide and persulfate chemicals and has annual sales of about $350 million. Without peroxygens, which Sandifer calls a “slow-growing business,” FMC can focus on better opportunities in agriculture and health and nutrition.

For Eastman Chemical, the game-changing transaction was last year’s $4.8 billion acquisition of Solutia. “We did our portfolio cleanup ahead of others,” says Mark J. Costa, Eastman’s president and CEO-designate. He points to the divestiture between 2007 and 2011 of businesses in polyethylene terephthalate resins, polyethylene, and coatings ingredients.

The Solutia acquisition was a “transformational step,” Costa says, helping align Eastman with sweeping trends in safety, security, and energy conservation. Key Solutia businesses include heat-transfer fluids and specialty films that are applied to glass for heat buildup control and safety.

Because Solutia had emerged from bankruptcy reorganization just a few years before Eastman bought it, the company had little money to invest in R&D, Costa says. Eastman changed that. In 2012, when it bought Solutia, Eastman’s R&D expenditure rose 25% to $198 million. Through the nine months ending on Sept. 30 of this year, the company boosted R&D another 9% from the year-earlier period to $148 million.

Advertisement

For Eastman and other firms, the portfolio rejiggering won’t ever end. Changes in corporate direction come with the territory, points out Steve Butler, a director at Cogency Chemical Consultants, an advisory firm that works for private equity firms.

“Back in the ’70s and ’80s, major chemical companies discovered portfolio management and they’ve not stopped reshuffling since,” Butler says. In the late ’90s, many rushed to get into fine chemicals, only to be followed a few years later by a string of exits from this area. Clariant, DuPont, Bayer and many others have substantially overhauled their portfolios more than once. “Are they backing the right horses now?” he asks.

Business mixes are always changing, Clariant’s Jany acknowledges, but it’s how you do it that matters. Portfolio management is more important now than it was 40 years ago, and executives have learned from past mistakes. “Specialties turn into commodities. That’s the natural evolution of things,” he says. “Portfolio management is necessary if we are to remain a real specialty chemical company.”

Discarded As A Commodities Player, Carbon Black Maker Orion Tries Its Own Product Differentiation

Orion Engineered Carbons was an unloved commodity business. In 2011, its original owner—Evonik Industries—wanted to get rid of it to focus on specialties and sold Orion to private equity firms Rhône Capital and Triton Partners for more than $1.6 billion.

Orion is a supplier of carbon black, a powder used mainly to reinforce rubber. But according to Mark Leigh, general manager for the firm in the Americas, Orion is now turning to specialties, just as big chemical makers have, as one way to buck up profits and differentiate itself from competitors.

Leigh, a former Evonik employee, says Evonik’s corporate strategy was to look for end products, such as tires, where many of its products could be used. The firm’s precipitated silica and silane became stars because they help customers produce tires that make cars more fuel efficient. Carbon black fell out of the limelight.

When Evonik divested the carbon black business, the new owners took another look at truck tires, where silane and silica don’t wear well. According to Leigh, the firm’s scientists are now developing carbon blacks that also have fuel-saving properties.

For ink customers, Orion has come out with a new carbon black pigment made from renewable plant oils instead of petroleum. Introduced in September, the Printex Nature line can be combined with naturally derived binder systems and solvents to make inks and coatings from up to 90% renewable ingredients, Leigh says.

The company also has projects under way to introduce carbon into other places where it can provide a benefit. For instance, carbon black is now used to increase electrical conductivity in lead-acid and nickel-metal hydride batteries. Additionally, the firm hopes to supply carbon black to makers of high-tech lithium-ion batteries, where the material’s conducting attributes could be beneficial, Leigh says.

Some customers will always be cost-sensitive and go with the lowest price product, Leigh says. Others will pay more for performance. To meet the needs of customers in the latter category, “we’ve now developed a specialties mentality,” he says.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter