Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Biological Chemistry

Probiotic Treatment Reduces Autistic Behaviors In Mice

Animals treated with a beneficial bacterium have improved gut health, and they vocalize more and repeat motions less

by Lauren K. Wolf

December 23, 2013

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 91, Issue 51

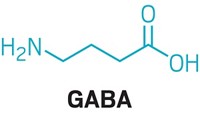

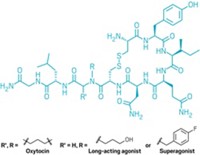

Population studies have shown that a portion of people with autism suffer from constipation and other gastrointestinal problems. A subset of these individuals also have “leaky guts”—that is, weakened intestinal walls that allow undesirable compounds to enter the bloodstream. Seeking to understand these phenomena, Sarkis K. Mazmanian and Paul H. Patterson of Caltech and colleagues studied the intestines of mice that display autismlike behaviors such as repetitive movements, antisocial tendencies, and impaired communication. The researchers generated these mice—a common animal model for autism—by triggering a severe immune reaction in pregnant females. In addition to exhibiting autistic behaviors, the offspring born to these females had leaky guts. A few weeks after treating the newborns with a one-week course of Bacteroides fragilis, a probiotic, or beneficial gut bacterium, the team found that the mice had stronger intestinal walls, vocalized more, and repeated motions less than their nontreated counterparts (Cell 2013, DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.11.024). Autism is a heterogeneous disorder that involves many genes, Mazmanian notes. But he says his team’s findings suggest that gut physiology plays a role and could lead to new treatments.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter