Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Policy

NIH Adapts Grant Resubmission Rule

Research Funding: Community concern that too much good science was being rejected fuels change

by Andrea Widener

April 25, 2014

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 92, Issue 17

The National Institutes of Health will allow scientists whose research grants have been rejected to resubmit funding requests a second time, the agency announced earlier this month.

Applicants who have rewritten their research grants once (stage A1) and had them rejected will be able to submit essentially the same application a second time. But they will have to submit the application as though it is a new grant (A0), with no reference to suggestions from previous peer reviewers.

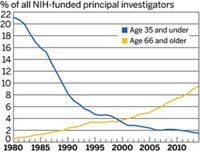

The move comes in response to an outpouring of concern from the scientific community that limiting grant submissions forces scientists—especially vulnerable early-career researchers—to abandon successful research pathways. The issue has become even more pronounced in recent years, as NIH grant success rates have dropped to record lows because of federal budget cuts.

“We wanted to be supportive of your concerns,” NIH Deputy Director Sally Rockey explained in announcing the policy change. “We believe this is a very positive move for our applicants.”

Until five years ago, grantees were allowed to submit essentially the same grant application multiple times. NIH changed that policy in 2009 in an attempt to lessen the burden on peer reviewers and to encourage reviewers to fund good grants the first time around.

“The policy that allowed only two strikes was very harmful to early-career investigators who were just learning their craft, and it was unfair to people who barely missed the payline,” says Howard Garrison, public affairs director for the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology.

The result was that scientists were often rewriting grants to make work they thought was important look new, even if it wasn’t. Now, “you don’t need to artificially reinvent the science,” says Seth M. Cohen, chair of the department of chemistry and biochemistry at the University of California, San Diego.

As a member of an NIH study section, which will likely receive an increase in applications, Cohen says, “It is probably a good policy change and a good compromise.” But it could force NIH funding rates even lower because of an increased number of grants. “It could make what is a difficult situation even worse.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter