Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

People

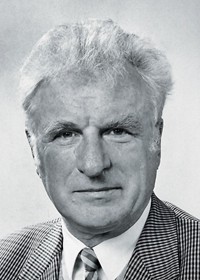

Cornforth Dies At 96

Nobelist’s work on stereochemistry of enzymatic reactions influenced generations of chemists

by Elizabeth K. Wilson

January 13, 2014

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 92, Issue 2

Sir John W. Cornforth, an Australian chemist who shared the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1975 for his work on the stereochemistry of enzyme-catalyzed reactions, died on Dec. 8, 2013. He was 96.

In a career that spanned some 75 years, Cornforth inspired generations of chemists with his strategies for using hydrogen isotopic substitution to trace the steps of enzymatic reactions. His Nobel Prize-winning work involved using such methods to show how nature assembles acetic acid molecules into cholesterol.

Judith P. Klinman, an emeritus chemistry professor at the University of California, Berkeley, recalls Cornforth as a kind and gentle man whose work had a profound influence on her. As a postdoc in the late 1960s, she says, she and her colleagues used Cornforth’s methodologies to study the stereochemistries of the interconversion of acetate with citrate, using three different enzymes. “It was the thrill of these early experiments that hooked me on a career studying the chemistry of enzymes,” she says.

Cornforth’s early work focused on penicillin and its purification. He and his colleagues also achieved the first total synthesis of nonaromatic steroids in 1951.

“Cornforth was one of the mid-20th-century giants of organic chemistry,” along with Nobel Laureates Robert Burns Woodward and Sir Robert Robinson, says William L. Jorgensen, a chemistry professor at Yale University who uses computational methods to study enzymes and drug design.

“Their successes in the days before NMR required remarkable insight, dedication, and perseverance,” Jorgensen adds.

Cornforth was born in Sydney and began studying chemistry at the University of Sydney at age 16. His story is also remarkable because the ear disorder otosclerosis left him deaf at an early age. Chemistry, and the accompanying laboratory work, offered a career where “deafness might not be an insuperable handicap,” he later wrote.

He met his wife, Rita, at the University of Sydney while they were both chemistry students. They both completed their Ph.D.s at Oxford University and were lifelong collaborators, sharing authorship on 41 papers. They had three children together. Rita passed away on Nov. 6, 2012, at age 97.

Cornforth became a professor at the University of Sussex in 1975, where he stayed for the remainder of his career, maintaining a laboratory until he was almost 90 years old. He shared the 1975 Nobel Prize with chemist Vladimir Prelog, who died in 1998. Cornforth was an emeritus member of ACS, joining in 1964.

Obituary notices of no more than 300 words may be sent to Susan J. Ainsworth at s_ainsworth@acs.org and should include an educational and professional history.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter