Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Materials

Seeds Sprout Select Nanotubes

Nanotechnology: Chemists create just one type of single-walled carbon nanotube from polycyclic precursor

by Bethany Halford

August 7, 2014

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 92, Issue 32

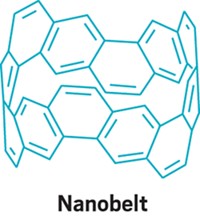

Using a 96-carbon polycyclic aromatic molecule as a seed, chemists have managed to make single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWNTs) of just one type—a long-sought goal in nanotechnology. Being able to make nanotubes of a specific type should help scientists better exploit their promising electronic properties.

Nanoscientists and gardeners have this in common: They spend time and effort in creating just the right conditions for something that ultimately grows of its own accord. They can poke and prod and try to manipulate their crop, but their control over what’s finally harvested is frustratingly limited.

Such has been the case for decades with SWNTs. These tiny tubes, which resemble rolled-up chicken wire, possess promising properties for electronic applications, but efforts to make them have always produced a mix of tubes with varying diameters and chiralities—the carbon-atom geometry that can make a nanotube behave like a metal or a semiconductor.

Now, scientists led by Konstantin Amsharov of Germany’s Max Planck Institute for Solid State Research and Roman Fasel of the Swiss Federal Laboratories for Materials Science & Technology report that by starting from a polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon precursor, they are able to make one and only one type of SWNT (Nature 2014, DOI: 10.1038/nature13607).

The seed molecule folds up into a nanotube cap when heated on a platinum surface. The nanotube then elongates as ethanol gas is added to provide a carbon source. The resulting nanotubes are metallic and free of defects. They are several hundred nanometers long and have a diameter of less than 2 nm.

It was already known that nanotubes would grow from such cap structures and that these caps ultimately dictate the nanotubes’ chirality and therefore their properties, Amsharov explains. “Our idea was to replace the spontaneous cap formation with caps of defined structure, which would lead to the formation of ‘programmed’ carbon nanotube architecture,” he says.

Although the seed molecule is made via multistep organic synthesis, Amsharov doesn’t think it will lead to an expensive nanotube-making process. “The kilogram-scale carbon nanotube synthesis would need just milligram amounts of the rather expensive precursor,” he tells C&EN.

Yan Li, a nanoscientist at China’s Peking University who recently reported a method to grow high-purity SWNTs, says Amsharov and Fasel’s team has taken “a very clever route,” which she expects could be modified to make nanotubes with different chiralities.

“The development of methods to synthesize single-chirality carbon nanotubes from the bottom up has been vigorously pursued in many laboratories worldwide, including my own, for many years,” notes Boston College chemistry professor Lawrence T. Scott. “Now, for the first time, that dream has finally been made a reality.

“At the present stage, the quantities of single-chirality SWNTs prepared by this method are too small to be useful for large-scale technological applications, but the principles have now been established,” Scott adds. “It will be up to engineers to figure out how to scale up the process to practical levels.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter