Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Synthesis

Newfound Enzyme Could Aid Synthesis

Enzymology: Halogenase chlorinates unactivated aliphatic carbons in non-protein-linked substrates

by Stu Borman

September 15, 2014

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 92, Issue 37

Adding halogen atoms to unactivated single-bonded carbon atoms in freestanding organic compounds remains a challenge for synthetic chemists. The discovery of the first enzyme capable of this feat may make it easier to carry out such halogenations in the lab.

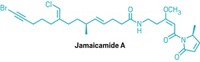

Natural products with halogen substituents—like the chlorine-containing antibiotic vancomycin and anticancer agent salinosporamide—are made by many organisms. The halogens have a big impact on these natural products’ biological activity, stability, and other molecular properties.

Halogens have an equally important influence on the properties of many lab-synthesized organic compounds. Iron-dependent halogenases could be useful tools for adding halogens to aliphatic carbon atoms in complex organic substrates to create chiral halogenated products. However, to be catalytically active, halogenases identified up until now required that substrates be tethered to carrier proteins. That’s a major inconvenience in the lab, where a substrate would have to be attached to a protein, reacted with halogenase, and then detached from the protein—a sequence of steps reminiscent of protecting-group chemistry and equally time-consuming.

If chemists could use an iron-dependent halogenase on substrates that don’t have to be attached to proteins, it might open the door to more efficient laboratory enzymatic halogenations. In a bacterial biosynthetic pathway that produces the natural product welwitindolinone, assistant professor of chemistry Xinyu Liu and postdoc Matthew L. Hillwig at the University of Pittsburgh have now identified such an enzyme (Nat. Chem. Biol. 2014, DOI: 10.1038/nchembio.1625).

WelO5, the iron-dependent halogenase they found, chlorinates aliphatic carbons in freestanding substrates not linked to carrier proteins. The orientation of the substrate in the enzyme’s active-site pocket controls which site is chlorinated. The new study also answered a long-standing question about the enzymatic origin of chlorine substitution in the welwitindolinone biosynthetic pathway and related pathways.

“We expect that this discovery ... will present new opportunities to evolve new catalysts for selective late-stage halogenations on unactivated carbons in complex molecular scaffolds,” the researchers write.

“Escaping the shackles of carrier protein is a big step,” comments iron-based-enzyme expert J. Martin Bollinger of Pennsylvania State University. “If you can evolve the enzyme’s selectivity to add chlorine at different substrate positions, then you can make biocatalysts for chiral chlorinations that would be very demanding to do synthetically.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter