Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Policy

Export Agency’s Survival Imperiled

Industry fights to save lender that helps boost overseas sales

by Glenn Hess

October 6, 2014

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 92, Issue 40

The Export-Import (Ex-Im) Bank of the U.S., which some hard-line conservatives have targeted for elimination, will stay in business for at least nine more months. But the chemical industry and other businesses that use the bank’s services are worried that the embattled 80-year-old institution’s days may be numbered.

The government lender, which facilitates U.S. exports, has historically enjoyed bipartisan support on Capitol Hill. But in recent years, more and more Republicans have turned against it. Tea Party-aligned conservatives, mostly in the House of Representatives, charge that Ex-Im Bank is an example of “crony capitalism” in which certain companies get favorable treatment from the government.

The little-known federal agency, whose charter was due to expire on Sept. 30, won a short-term extension from Congress last month. The brief renewal was tucked into a government funding measure lawmakers passed before hitting the campaign trail for the midterm elections.

But the temporary reprieve hardly satisfies the bank’s industry advocates.

“A limited, short-term extension of the Ex-Im Bank’s mandate—while better than nothing—doesn’t provide the sort of certainty that businesses prefer when considering whether to expand or develop new business ventures,” says Michelle Orfei. She directs regulatory and technical affairs at the American Chemistry Council (ACC), a trade association that represents more than 140 U.S. chemical companies.

“We need Congress to pass a full five-year reauthorization to support U.S. exporters as soon as possible,” adds Kevin M. Kolevar, Dow Chemical’s vice president of government affairs and public policy. “Uncertainty creates a difficult environment for businesses to plan and operate.”

Trade Financing Agency

The Export-Import Bank was established in 1934 by a presidential directive. In 1945, Congress made it an independent agency within the executive branch.

The bank’s mission is to create and sustain U.S. jobs by financing sales of manufactured goods to international buyers, primarily when alternative financing is not available. The transactions are backed by the full faith and credit of the U.S. government.

The bank provides

◾ Direct loans to foreign buyers of U.S. goods and services, usually for capital equipment and services.

◾ Medium- and long-term guarantees of loans made by a lender to a foreign buyer of U.S. goods and services. If the buyer defaults, the bank promises to pay the lender the outstanding principal and accrued interest on the loan.

◾ Working-capital repayment guarantees to lenders on secured, short- and medium-term working-capital loans made to qualified exporters.

◾ Insurance policies to exporters and lenders to safeguard against nonpayment because of commercial risks, such as bankruptcy, and political risks, such as war.

Ex-Im Bank was created in 1934 by President Franklin D. Roosevelt as a New Deal program to help rebuild Depression-hit industries and spur job growth. Both a bank and a federal agency, it offers loans to foreign buyers of U.S. products and working-capital guarantees, insurance, and other assistance to domestic exporters—all at no annual cost to the U.S. taxpayer.

The bank pays for its operations through interest and fees on its assistance and hands over its profits to the Treasury Department. Last year, Ex-Im provided $27.7 billion in assistance to support an estimated $37.4 billion in U.S. export sales. It also sent a record $1.1 billion in profit to the U.S. Treasury.

“The Ex-Im Bank is designed to help U.S. companies have access to the credit they need to turn export opportunities into sales,” explains Lawrence D. Sloan, chief executive officer of the Society of Chemical Manufacturers & Affiliates (SOCMA), a trade group that represents 220 mostly small specialty chemical makers. “Many of our members are Ex-Im Bank clients,” Sloan says.

The chemical industry is capital-intensive and often requires multiple funding sources for new projects. For example, when Dow and majority partner Saudi Aramco sought financing for the massive Sadara petrochemical complex they are building in eastern Saudi Arabia, they received funding from a variety of traditional commercial lenders.

But the $19.3 billion megaproject required even more funding than what these lenders could offer, Kolevar says. So Dow worked with Ex-Im to secure a nearly $5 billion loan, the biggest in the bank’s history. When complete in 2016, the sprawling complex will consist of 26 processing units producing more than 3 million metric tons of 10 categories of chemical products and specialty plastics per year.

Some 80 U.S. companies, including more than 20 small businesses, are providing parts, machinery, and components to the facility in Jubail Industrial City II. As a result, the Ex-Im Bank loan “supports over 18,000 jobs in more than a dozen states,” says Kolevar. “Small and midsize companies benefit indirectly from larger company loans, as we source export content from their operations.”

Ex-Im Bank operates under a charter that Congress has renewed 16 times, usually without rancor. As recently as 2006, the charter was extended for six years by the unanimous consent of both the House and the Senate. Congress easily reauthorized it for two years in 2012, despite some Republican opposition.

But this year, the bank has emerged as a focal point in the long-simmering feud between the pro-business wing of the GOP and the growing Tea Party faction over the extent to which the government should be involved in the economy.

Leading the drive to end Ex-Im Bank is Rep. Jeb Hensarling (R-Texas), chairman of the House Financial Services Committee. He’s backed by many conservative Republicans as well as influential right-leaning groups such as the Club for Growth, the Heritage Foundation, and the libertarian Cato Institute. They argue that a government program that helps companies export products overseas distorts the free market.

Hensarling calls the bank a “poster child of the Washington-insider economy and corporate welfare.” In the congressman’s view, the bank chooses winners and losers, giving large corporations that have political clout unfair advantages over their smaller counterparts.

“We need to level the playing field so American manufacturers and small businesses can compete,” Hensarling says. But Ex-Im Bank “overwhelmingly and indisputably [benefits] some of the largest, richest, most politically connected corporations in the world.” In 2013, he says, over half of the bank’s financing “went to a handful of Fortune 500 companies.”

The charge is “unfair, inaccurate, and inflammatory,” Kolevar says. “Ex-Im is available to any company in the U.S., not a select few.”

Ex-Im Bank statistics show that nearly 90% of its 3,842 export transactions in fiscal 2013 benefited small businesses, an all-time high. At the same time, 76% of the value of loans and guarantees went to the top 10 recipients, a list dominated by corporate giants such as Boeing, General Electric, Bechtel, and Caterpillar.

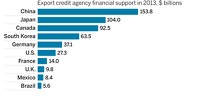

Supporters say that closing the bank would put U.S. businesses at a competitive disadvantage in the global marketplace. Ending Ex-Im would amount to unilateral disarmament because 60 foreign countries—including China, Germany, France, and South Korea—have their own export credit agencies, warn the bank’s backers.

“For any company seeking to compete effectively internationally, reliable access to cost-effective export financing and services is vital, particularly when many of our trading partners are providing these services to their companies,” ACC’s Orfei says.

The effort by conservatives to let Ex-Im Bank’s charter expire gained momentum over the summer after then-House majority leader Eric I. Cantor (R-Va.) suffered a stunning primary loss. Cantor had forged the bipartisan deal in 2012 to reauthorize the bank.

Cantor’s successor in the House leadership slot, Rep. Kevin McCarthy (R-Calif.), declared in June that he would like to see the bank closed. Financing exports “is something government does not have to be involved in,” said McCarthy, who in past years had backed the agency. “I think the private sector can do it.”

But heavy lobbying by the business community helped persuade House Speaker John A. Boehner (R-Ohio) to include a renewal of the bank’s charter through June 30, 2015, as part of a “must-pass” measure to keep the government running until mid-December. After quick passage by both chambers, President Barack Obama signed that budget resolution into law on Sept. 19.

Hensarling says the extension will give lawmakers an opportunity to consider the bank’s future on its own, rather than as part of a federal funding bill. “Although this agency is small in scope, it is incredibly important in principle and direction. Members ought to have an opportunity to understand the issue, debate the issue,” he says.

Putting that discussion off until the middle of next year gives Republican lawmakers more time to reach consensus on whether to try to overhaul the bank’s authorities, start the process of winding it down, or simply do nothing and let it expire. But it also gives supporters more time to argue their case for a long-term extension of the bank’s charter. The Obama Administration and most Democrats want a five-year renewal.

“We cannot let the bank lapse and are happy that congressional leadership has recognized that fact,” Kolevar says. “But the reality is that manufacturers and small businesses are depending on a multiyear reauthorization to ensure that they are able to compete and win overseas, in turn driving job creation here at home.”

There is “definitely some room for improvement” in the way Ex-Im Bank operates, acknowledges SOCMA’s Sloan. Changes are needed, he says, that would “help to increase the bank’s efficiency at the lowest possible risk to taxpayers.”

One possible solution is legislation being drafted by conservative Rep. Stephen L. Fincher (R-Tenn.), who opposed reauthorization in 2012. Fincher says the planned bill would overhaul the bank to make it more transparent and accountable and keep it open for five more years. Fincher expects to unveil his proposal before the end of the year.

“We feel that the Ex-Im Bank should be reauthorized with some reforms because, for some of our members, there may not be another viable option for securing financing,” Sloan tells C&EN. “It’s really the only way that some of our members can afford to continue to export and build a business.”

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter